by karolina on 23 September, 2011

‘Where the little inmates are permitted to grow up natural and normal human beings.’ Inside assistant curator Karolina Kilian came across this 1933 Australian Women’s Weekly article about the Church of England Homes for Children.

We’ve transcribed the article so that it’s easier to read:

Gone are the days when institutions for children were like dull morgues, when discipline amounted to tyranny, and all suggestion of love or affection was killed at birth.

The children’s homes of today are pleasant, cheerful places, where the little inmates are permitted to grow up natural and normal human beings.

The Church of England Homes for Children are typical of the changed order. Visit any of the institutions controlled by this committee and you will find conditions that many children under parental roofs might envy.

Hundreds of girls and boys who have passed through these homes are now occupying good positions throughout the Commonwealth.

It is a delight to attend one of the gatherings at the home and meet young men and women who are so proud of their early association with the homes as are men and women who boast of their association with noted schools of learning.

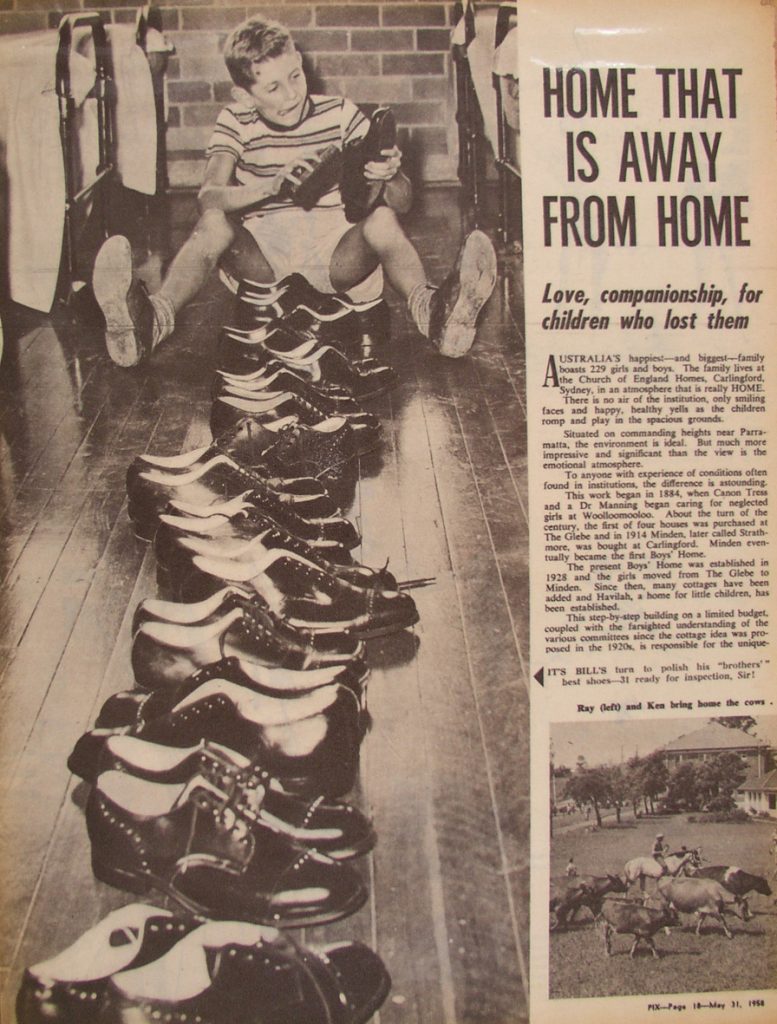

There is a group of these homes at Carlingford (for boys and for girls), a girls’ home at Leura, and the Havilah Home, Wahroonga, for young children.

The homes all have the advantage of being set in beautiful grounds, of having fresh milk and home-grown vegetables.

Built on the crest of a rise at Wahroonga, in a setting of spacious lawns, orange groves, and shrubbery, Havilah Home cares for 80 children between the ages of two and seven years.

Girls on reaching the age of seven are transferred to Carlingford, which takes girls from the age of seven to twelve, to remain there, of course, until the time when they are able to earn their own living or suitable care is guaranteed for them. This home has accommodation for 150 girls, and this is not sufficient. Applications are refused every day, and there is a long waiting list. An even larger demand is made on the boys’ homes.

The other girls’ home is at ‘Quipolli’, Leura, where there is accommodation for 28, from the age of seven to the time when they are fitted to face the world alone.

Domestic science, cookery, dressmaking, laundry, hospital training, and lace-making are among the crafts taught the girls. Lace-making is a special feature, and overseas visitors have compared it with advantage to that done by the women of France and Belgium. Quite a number of girls have their own gardens, for which prizes are awarded.

The Boys’ Home at Carlingford stands in 45 acres of grazing property. The boys receive tuition in carpentring, boot-repairing, house and farm work. In every way they are taught to develop a spirit of self-reliance, wholesome living, and usefulness. They attend the public school at Carlingford, belong to the Boy Scouts, and have a fine choir. On June 3 of this year a large workshop was presented by Mr F.E. Penfold.

History of the homes commences in 1863, at Woolloomooloo, when initial efforts were made to help destitute women and children by the late Canon T.B. Tress and the Rev. J.N. Manning, two Anglican gentleman whose names are commemorated in the Tress-Manning Home at Glebe Point, Mrs J.N. Manning, who is now 83 years of age, as a senior member of the executive committee, still attends the meetings.

From Woolloomooloo a move was made to Paddington, and further expansion necessitated a transfer to Darlinghurst, and in 1894 a group of girls’ homes at Glebe Point was established. The first homes were established at Carlingford in 1929.

No mention of the Church of England Homes for Children would be complete without reference to the late Matron McGarvey, whose love, understanding, and wisdom were of such great influence in the condust of the institution.

Miss McGarvey was matron of the homes for 35 years. It was largely owing to her efforts that the Carlingord Home for Girls was established. As Glebe Point developed more and more into an industrial area, she longed for a country environment for the children. She saw her ambition realised, and was at the Carlingford Home for a while before her retirement in February, 1930.

Miss McGarvey died in December of the same year.

Where children receive their natural heritage – The Australian Women’s Weekly, 2 September 1933 (PDF 241.9kb)

You can also access the article and The Australian Women’s Weekly through the National Library of Australia’s TROVE search service for digitised newspapers, magazines, photographs and more.