by Junita Lyon (guest author) on 1 March, 2010

Junita Lyon, a resident of Parramatta Girls Home in 1970–71, remembers her time in the institution.

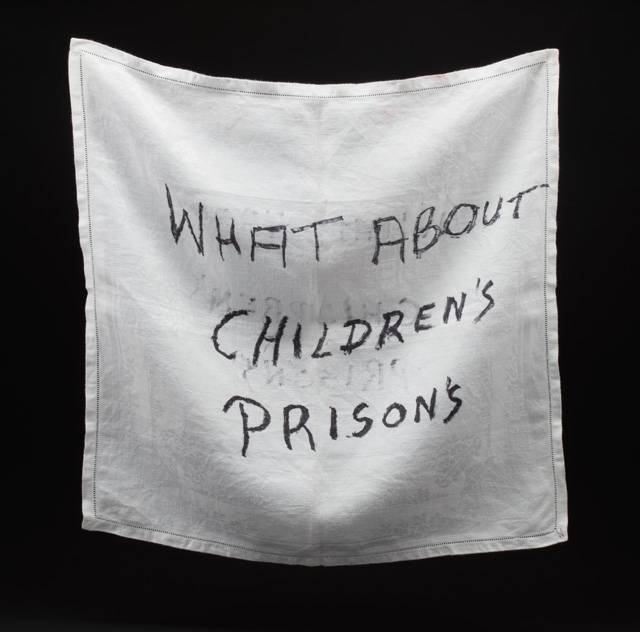

During my childhood I was committed to Parramatta Girls Training School where many degrading acts were part of Policy and Procedures.

On arriving at Parramatta I was held for hours in a holding room. Taken away and given a number and fitted for various types of clothing such as shoes, twinsets tartan skirts, underwear smocks and socks. My long hair was cut like a page boy, it devastated me and I was taken to dormitory 2 to start my 12 months committal period.

Every morning we were woken early and had to stand at the end of our beds and display our sheets to an officer, to make sure that we had not soiled or wet them. We would then make the bed to procedure and head of to our pre breakfast work.

We started our hard working day early, some went off to yard duty to pick up rubbish or sweep, others cleaned and scrubbed the dormitories before breakfast muster.

We would muster each time the bell rang and would stand to attention while being yelled at or belittled. Left Right Left Right Left Right we marched, we didn’t go anywhere with out some officer marking time.

In the morning we would be marched to breakfast to porridge with weevils, sweet warm white tea and white bread that every one said was made at the prison next door and they had ejaculated in it.

If we needed medical assistance or had our periods and wanted a pad, we would have to wait for help then it was a public ordeal, having to show the pads to prove if we were having a heavy period or not. There was no privacy at all.

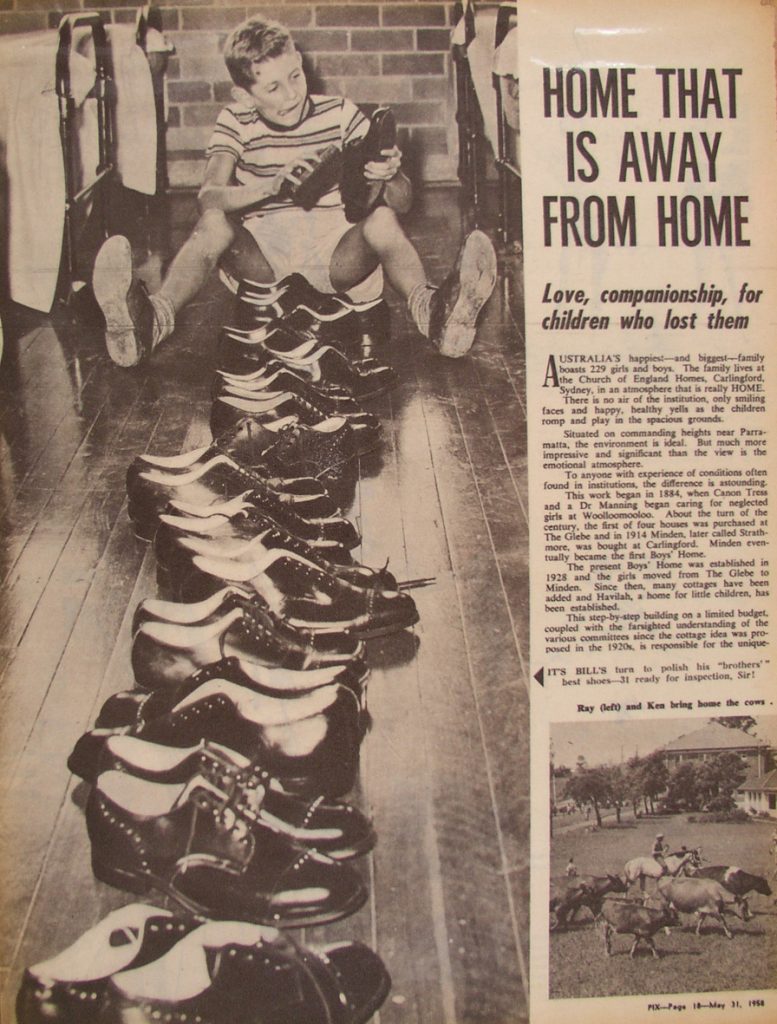

After breakfast and a quick recreation break we were assigned to a variety of Jobs a few were able to continue their education but nearly all were trundled off to the kitchen sewing room or laundry to Iron, wash, scrub or fold, a thankless task as was anything we did at Parramatta, I never heard praise for a job well done.

The laundry was a hard place to work we worked at the same pace as adults, it was hard on your legs and back and the temperature was unbearable, if you behaved you could get the opportunity to change jobs. Generally most of the girls were standing at ironing boards ironing from morning till late afternoon the work was repetitive and caused aches and pains to the body.

While in the laundry the job that I aspired to was to use the large industrial washing machines as I was bad at ironing, this was also hard work lifting heavy bundles of clothes.

After my time in the laundry I got a job painting the dormitories and other areas of the home, we worked in a small group and I painted one dormitory after another. It was sad to have to paint over the written history the girls had scratched on to the dungeon walls.

The painting job saved me from more trouble as I had to behave to keep the job and the officer that was with us was a very old lady who gave us a bit more freedom to talk, than anyone else there.

We were given chocolate cake and milk to absorb the lead paint we used.

I often heard my name called “under the bell” that would mean punishment either Isolation or scrubbing.

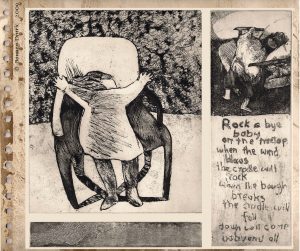

I spent time in Isolation; I actually liked the 24 hour stint, time to be on my own, I vented my anger, pain, frustration and confusion in written form on a blackboard which was the only thing in the room.

It was during these times I would think about the events that lead me to Parramatta and my drug addiction, why after so much pain, why more was being inflicted, Isolation was where I cried.

Scrubbing was the most common punishment and we often scrubbed the pigeon loft or cover way in groups called scrubbing parties.

The pigeon loft and I were common companions I remember the bird poo running down my arms and upsetting my eyes, kneeling scrubbing boards then standing scrubbing rafters, till my knees were raw for days on end from early morning till late at night depending on which officer I upset. Often we were set to work scrubbing the cover way with a scrubbing brush or toothbrush.

This cold lonely punishment was quite frightening at night for a 14-15 year old; often a girl could be left there scrubbing and almost forgotten about.

Punishment seemed to be given out at random, one time I spent 3 days with steel wool shining a rubbish bin with no cover during winter and another time I had to stand face to face with another girl and not smile or laugh for a whole day.

One time I was grabbed by the ears and my head was bashed up against a wall, this was a regular occurrence for many of us girls.

One cold night I was scrubbing on my own on the cover way and was called into the office I then had my head bashed into the wall till I cried.

That night I decided I wasn’t going to be bashed again so set up a devious plan.

The first chance I got I found a rock and smashed my head with it, so there was blood dripping down my face, I screamed and yelled, that It was caused by the bashing.

I had been pushed too far and my time as a street kid had taught me to protect myself.

I get sad when I think of this moment the fact, that I had to inflict self harm to myself to protect myself from my carer still gives me a chill to this day.

We lacked any privacy to undergo personal hygiene the toilets had no doors and we were given only a few sheets of toilet paper, a humiliating event.

I also remember the fear that welled up, during the time we would stand naked in a cubicle and an officer would walk around and have us drop our towels and inspect our naked bodies for tattoos, scratching and pins.

Some officers were creepier than others in the way they did this task and made you feel very uncomfortable or quite terrified.

Before we had a shower of an evening we also had to scrub the crutch of our underwear and show it to an officer.

All these sanctioned acts were degrading and have haunted me all my life…

Our escape from misery and brutality as young girls was to each other; our friendships were often intense and emotional. We crocheted hankies and wrapped soap in them as gifts to our special friends.

During our short recreation time, records and dancing under the cover way was how we spent our time, being careful not to be caught doing anything against the rules.

We danced the Parramatta Jive to songs such as blue angel and band of gold.

During this time we almost felt normal.

During dinner if you dropped your peas off your plate, talked or did anything menial you washed all the dishes, when everyone had finished.

There was always an officer on the prowl to look for someone to punish.

After dinner, if a dormitory had behaved overall 1 to 5, except 3, were able to use the recreation or TV room sitting on cold hard metal chairs in a cold hall watching a show that you never got to see the end. Usually dormitory 3 were standing at the end of their beds; during my time there this was the group punishment.

I only got to go in the rec room once, so we lost privileges easy.

Not many girls had visitors as many girls had spent there lives institutionalised or in foster care.

Those that did have visitors would meet them, on the cover way on a Sunday and many girls were randomly body searched after the visit.

There were certain girls that officers would take a dislike too, if you were singled out for punishment you would most likely end up at Hay. So the threat of more brutality was always hanging over our heads.

During my stay I spent time in dormitory’s 2,4,3,5,6 I saw a lot of injustice.

We as children needed protection and nurturing we were not given that protection and were often abused and degraded by the officers and treated like hardened criminals. Most girls in Parramatta were committed because they were neglected, abused or unloved.

The courts would then charge the girls with exposed to moral danger and commit them to a 3,6,9 or 12 months committal period. I saw many girls return after a few weeks of being let out as they were sent back to their abusers and didn’t cope. Life was tough and unjust for a Parragirl.

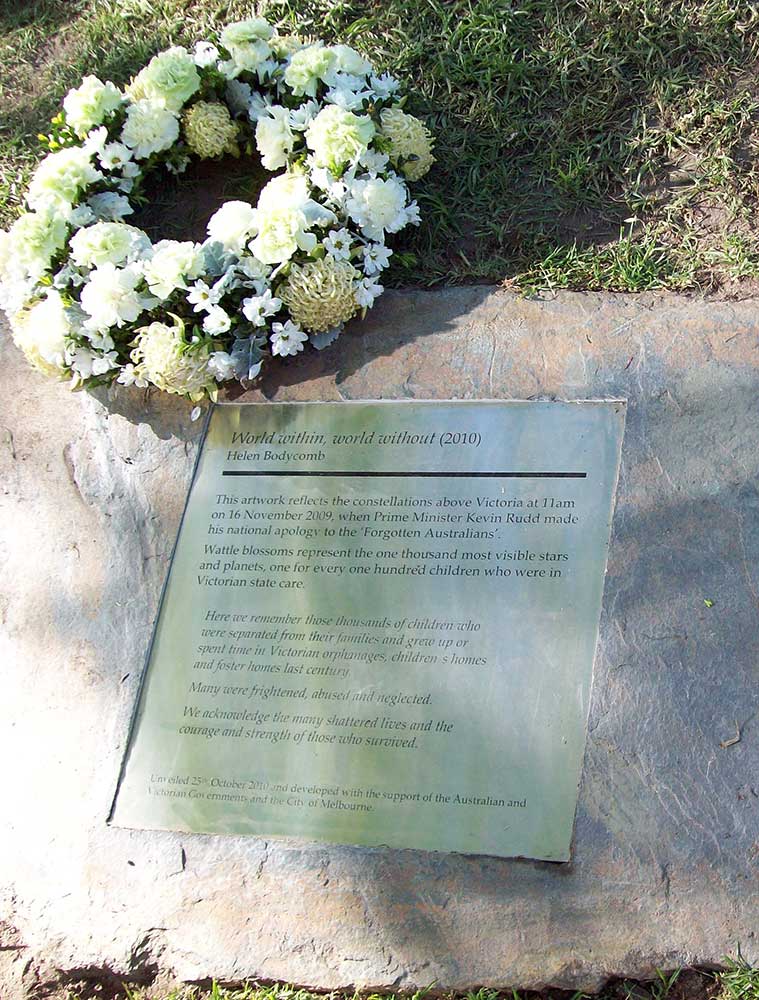

On the 16th of November Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made an apology to the “Forgotten Australians”

I welcomed this apology as my time in care has haunted me my whole life.

For me this apology is life changing, it validates the abuses of my child rights that occurred and gives me back my self worth.

I was a small child subjected to harsh punishment; criticism and lack of nurturing that affected my development and sent me spiralling into despair for many years.

It created family disengagement, lack of education and left me with low self esteem, and the inability to feel any belonging.

It created in me an outcast a loner, hiding in shame that did not fit in with others.

An apology cannot fix the damage already done but it creates in me a feeling of relief because it removes the feeling of guilt and shame I have lived with.