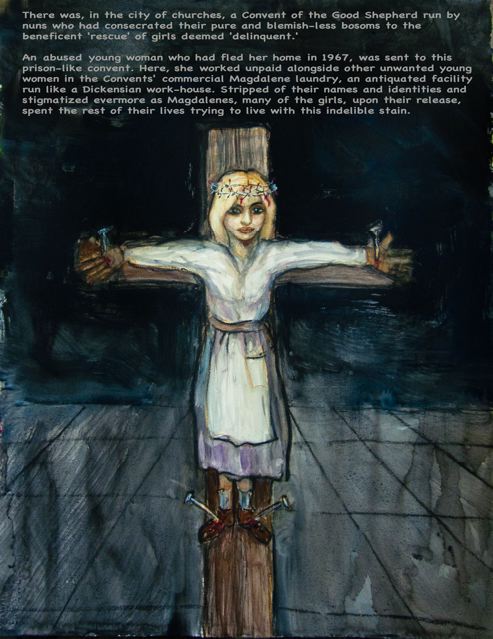

Interdisciplinary artist Rachel Romero is currently creating the Magdalene Laundry Diary drawings for her forthcoming film.

Here is one of these works, Stigmata: The Indelible Stain.

Copyright Rachael Romero 2011

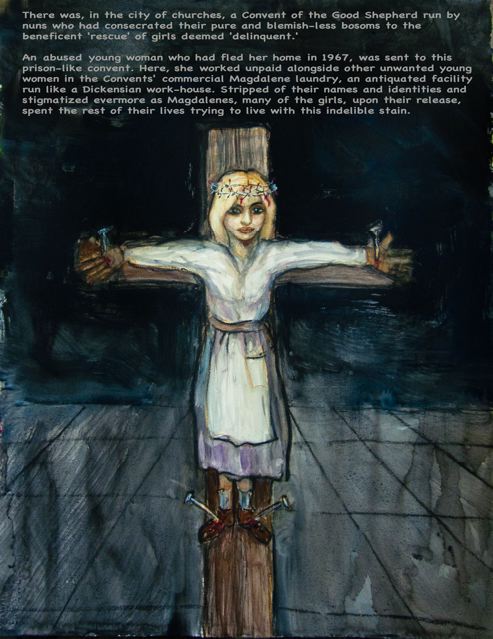

Interdisciplinary artist Rachel Romero is currently creating the Magdalene Laundry Diary drawings for her forthcoming film.

Here is one of these works, Stigmata: The Indelible Stain.

Copyright Rachael Romero 2011

by Ann McVeigh (guest author) on 2 August, 2011

‘My identity was stolen from me’. Child Migrant Ann McVeigh shares her personal history and photographs of St Joseph’s Orphanage, Subiaco (now Wembley), WA.

As a child migrant my identity was stolen from me the moment I left my home land, without my mother’s consent. The name that I was born with was changed when I was put into Nazareth House in Belfast. I came to Australia on the [SS] Asturias when I was 5 years old in 1950.

On arrival in Western Australia I was sent to St Vincent’s Foundling Home in Wembley till I turned ‘a big girl’ 6 years of age. When one turns 6 one is sent to St. Joseph’s Orphanage which was next to St Vincent’s. Once placed there I still had my name changed and the date of my birth was changed also. Right away we were given numbers to answer to, put onto our clothes and lockers, my number being number one. Straight away you were expected to work always rising at 6 am every day for prayers and Mass. Duties being – sweeping yards, cleaning toilets, washing and polishing floors in the dormitories, classrooms and long corridors on hands and knees. Children were put in charge of children to be cared for in nurseries, kindergarten and foundling home. Laundry had to be done for private boarding schools and hospitals as well. Huge big washing machines, dryers and mangles which were like oversized irons for sheets and the like. The work was relentless and very tiring.

A lot of the child migrants were, I feel, abused both physically and mentally simply because we didn’t get visitors and had no-one to report the abuses to. Girls were constantly being told that ‘from the gutters of Belfast you came and to the gutters of Belfast you’d return’. Schooling was always under duress, beltings if exam results weren’t good enough or if you couldn’t understand what was being taught. To my mind it was likened to a modern day Oliver Twist, with all the cruelty that went on.

When I was in grade 2 I was informed that I was a very lucky girl because I received a letter from my mother. I was called up to the front of the class whilst the letter was read out to me. I never ever forgot that letter and always wondered when I would get a visit from my mother who said she’d try and come to get me to take me back to Ireland. Every time the door bell would go you’d stop and wait with hope, expecting your name to be called. In the end it would be a joke – yeah she’s walking across water to get me – not ever realising my letters that you wrote were never passed on. My education ended in second year high when I was 15 ½ years. I was sent 300 miles up north to look after 5 children and help around the house. One day I was with 200 kids, the next day 5 children and 2 adults. The quietness was frightening as I missed my school pals terribly. That job lasted six months and the second job for only one month, another country job doing housework for a very nasty and cold family. I was never ever greeted the time of day – just given orders on what had to be done for the day. No payment ever received. The third country job was as a shop assistant which I really enjoyed, but after 11 months I was very upset when told I would have to go back to St. Joseph’s. When her son came to pick me up I locked myself in the bathroom until I was given an assurance that I wasn’t going back. I was sent to a juvenile detention centre which scared me somewhat when I woke up the first morning as there were bars on all the windows and I thought that I had been sent to jail.

Because I rebelled I was given a welfare officer to help me out with jobs and accommodation. It was she who got my mother’s address and encouraged me to put pen to paper. Because I was eighteen I had to correspond by mail till I was allowed to go overseas and visit the family when I turned 21. When I first started to write, my mother told my siblings (2 brothers and 4 sisters) that I was their cousin from Australia. As they were still very young and still at school, not much explanation was needed. In 1967 I met my family for the first time. Being shy, I was very nervous, wondering if I was going to be accepted, but I needn’t have worried as everything turned out well.

When my mother passed away, I took my one year old son with me to the funeral. Sadly, she was buried on my birthday. When my son was eleven, I took him over again so he could meet all his cousins. It was wonderful to see them all together, it was like he belonged and was wonderful to see.

In 1988 I bumped into a school pal and she was telling me that when she received her personal papers from the welfare department, she had a breakdown. You see, because of her Afghan heritage she was dark skinned and in her papers said, although she was a very pretty little girl, she was unsuitable for adoption. We got talking and wondered how the other girls had faired when they got files. She told the doctors that …. the treatment the girls got at the home would come out – so he went to the Wish Foundation and formed an organisation called ICAS (Institutional Child Abuse Society). We went to print and on air and received a lot of support, especially after the radio interview. We got a lot of calls from the boys who were in Clontarf, Bindoon, Tardun and Castledare, telling us about the abuse that took place. We only heard from one or two other girls that they weren’t interested and just wanted to forget. After all this happened the boys formed their own organisations and the world got to hear of the terrible treatment the migrants and Aussie kids received in the institutions of the day.

I was on the committee that erected the child migrant statue in Fremantle, outside the Maritime Museum. My partner is a child migrant also and both our names are on the Welcome Wall, very close to the migrant statue. While on the committee, submissions were invited for the Child Migrant Memorial Statue, although my poem wasn’t accepted, these are my thoughts on the very sad history of child migration.

They did not know what lay in store

holidays abroad to far distant shores.

Yet in their memories as often recalled,

brothers – sisters

and friends what’s more.

Where are the families

that they once had

Back in their homelands,

How very very sad

Thousands of children crossing the line

Holidays and memories lasting a lifetime

Ann McVeigh 29 January 2011

by Rachael Romero (guest author) on 8 June, 2011

Rachael Romero, who was in the The Pines, the Convent of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd in Plympton, South Australia, shares her drawing A Severed Life.

Rachael writes about her art work:

Those responsible for our incarceration were looking in the mirror.

How many lives cauterized?

How many hands maimed?

Girls not protected but stained by unwarranted and self-righteous religious and civil presumption of guilt.

Their persecuters were looking in the mirror.

by Rachel Romero (guest author) on 18 May, 2011

New York artist and film-maker, Rachael Romero, and former resident of ‘The Pines’, Sisters of the Good Shepherd Convent, Plympton, South Australia shares a page from her book which will be published this year.

Rachael’s book is a series of prints documenting the life in the Convent of the Good Shepherd. Regarding her work below, The Mangle, Rachael says,

You … need to imagine immense heat, little ventilation and the din of thundering machinery.

by Rachael Romero (guest author) on 2 May, 2011

In 1971, Rachael Romero, soon after her release from The Pines (Sisters of the Good Shepherd Convent), Plympton, SA, wrote a poem about how it felt to be indoctrinated.

Of Pines Indoctrination

A tattooed mind

with fear and cold

and logic warped

to please false aims

a cringing heart

a slaughtered soul

a bleeding confiscated mind

Deadened, buried lay my will

Hushed with fear and violent threat

Unwanted, stifled, broken, ill

stumbling on a stormy deck.

copyright Rachael Romero

by Raymond Brand (guest author) on 13 April, 2011

Former Child Migrant Raymond Brand writes about his experience as a child migrant from Britain, growing up in Castledare and Bindoon, WA. Ray describes the abuse he suffered and how education and medical care were low priorities at Bindoon.

by Janice Konstantinidis (guest author) on 10 March, 2011

In January 2010, Janice Konstantinidis returned to her former “Home”, Mount Saint Canice, Sandy Bay, Tasmania to witness its redevelopment into luxury apartments.

Janice describes her feelings returning to Mount Saint Canice:

I am walking about the grounds….a first as a free person [and then] I sat here for a long time, trying to get my mind around it all. It was so weird to be free, even at fifty nine. In all seriousness I had flashbacks and wondered if I could be made stay.

by Rachael Romero (guest author) on 10 March, 2011

Rachael Romero who was sent to the The Pines, Plympton, SA, run by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, recalls the importnace of holy cards:

Holy cards were currency -emotional currency–in a place where expressions of contempt are the norm; where you can’t trust anyone because of co-ersion and it is unwise to share secrets, the holy cards where a sanctioned (because purified) way of showing loyalty and caring between people–to say what otherwise may not be said–to give each other courage. We weren’t allowed to speak more than an hour a day–otherwise we were in silence and the thundering noise of the Laundry Mangle or being raved at by the head nun as we ate the rotten food. Allways watched, we could buy the cards for pennies from the nuns and sometimes we were given them as gifts. We could not pass notes or letters unless the nuns read them first but the holy card was ok. It carried our “voice” however coded, however muffled.

They were given on Feast Days and Birthdays because we had no other gifts. We got 20c every week towards buying our own shampoo, soap, tooth paste–and holy cards, from the nuns.

by Rachael Romero (guest author) on 2 March, 2011

Rachael Romero shares her original art work which she painted in 1973.

Rachael recalls:

We couldn’t make noise in that cement quadrangle.We screamed in aching silence.

Silent Scream

copyright Rachael Romero 1973

by Rachael Romero (guest author) on 2 March, 2011

In these two original poetic works, Rachael Romero reflects on her experiences at The Pines, an institution for girls in Plympton, South Australia.

What is wild? by Rachael Romero, reflecting on entering The Pines

What is wild

Child

Not meek, not mild

Defiled

Exiled

Reviled

Child

MAGDALENE LAUNDRY

The stigmata of

religiously tattooed

Magdalene slaves

scourgings of

“fallen women”,

scars from

inmate labour

laundry work

hard physical

against the will work,

disfiguring injury

to hands and minds

now and always

Branded and

besmirched by

vituperative

nails-through-the-palms-

language

religious scourgings

marks of experience–pain

onto legs

bellies

Branded by injurious insult

religious tattooing of the mind

forced

physical labour

such as laundry work

agains- the-will,

side-by-side nail marks

Christ inflicted pain

Magdalene self-injury

cigarette burns to

know what Jesus felt.

PENITENCE

the identifiable stigma of slaves

hard labour institutions,

stigmata people

ancient

branded.

on my body

the same wounds

symbols of pain

and slavery

marks of ancient inmate identification by order of the church, state order.

by Rachael Romero

by Janice Konstantinidis (guest author) on 28 February, 2011

Janice Konstantinidis, shares a current photograph, as well as her detailed history of her time from the age of 12 working in the laundry of Mount Saint Canice, Tasmania, one of the Magdalena laundries, nicknamed “The Mag”. Janice also includes recollections of the lengths some girls would go to in order to escape.

Mount Saint Canice

At the age of twelve, I was taken by my grandparents and father to Mount Saint Canice, one of the Magdalene Laundries. The laundry was run by the Order of Good Shepherd Nuns in Hobart, Tasmania. There were a number of these laundries in Australia, as well as in other parts of the world. I am not sure how or why it came to pass that women and children were taken in by the nuns, but I know that the courts had no hesitation in sending adolescent girls to these homes for punishment. It was also common for parents to place their children in these homes when they could no longer house them, or for any number of reasons. It is not my purpose to speculate here as to why the state allowed this and, indeed, there has been an inquiry and subsequent public apology to all of us who were incarcerated in this manner. It is important for me to write my own record of my experiences so that it can become public knowledge. In doing so, I hope that no child now or in the future ever has to experience the horror I did.

I had been told that I was going to Mount Carmel, a Catholic boarding school in Hobart. My father had been asked to find a school for me as his parents, who were unwell, were no longer able to care for me. My father was a sadistic alcoholic, and he had lied to my grandmother about where I was going. In her mind, the nuns could do no wrong.

My first day at Mount Saint Canice began at six a.m. It was pitch black and cold. The lights were turned on, hurting my eyes, as a nun came through each dormitory calling out loudly “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit”. All of the inmates got out of bed and fell to their knees. I was to learn that this command was to be obeyed immediately upon penalty of losing a mark. I will talk about marks later.

I also got out of bed and dropped to my knees. We said the Lord’s Prayer in unison. I was then told by a girl next to me to make my bed, and to get washed and dressed. We lined up at the unlocked door and waited until all were assembled, before filing through the next dormitory and down two flights of stairs. As I type this, I look back and realize that there were no exit signs and no fire escapes in that particular area. Even so, the doors were locked at every turn. We would have been in serious danger had a fire ever broken out.

We walked silently through two more doors, our numbers growing as each group joined us. We eventually ended up in the convent church. We, the girls from the home, had a part for ourselves that had been sectioned off, although some of the older girls sat in the public area. The nuns had their section as well. We had to attend Mass each morning. I was Catholic, so this was not new to me; but many girls were not and, therefore, resented having to attend Mass. I have to say that I resented this as well, as I did not have a strong belief in God.

We were not allowed to speak at all. When Mass was over, we filed back in order, based on who had come from where. Once assembled, we made our way to the refectory for breakfast, which was usually oatmeal with milk, and toast with butter and jam. After breakfast, we filed out of the refectory. I was escorted to a huge room by Judith, who was an auxiliary nun, and told that it was the ironing room. There, I was introduced to Mother Marguerite, who was in charge of this area. I had never seen anything like it. There were ten large cloth-covered ironing tables that ran through the middle of the room. These were duplicated, so there were twenty places at which the girls would iron. There were huge steam pressers and steam egg-like implements used for pressing clothes. These ran along either side of the tables. There was also an area that led to the next room, and just nearby, there were many bins of wet clothes waiting to be ironed.

I was shown to a table near Mother Marguerite, who was ironing. She pulled a bin towards me and informed me that it was my job to iron handkerchiefs until the bell rang, and that I would then be collected for school as I was a school girl. Once again, I was told that there was to be no talking. I was shocked, to say the very least, at this turn of events. I had no idea what was going on, but I began to iron the handkerchiefs obediently. This and other laundry work would be my employment until I left Mount Saint Canice at age 15 and a half.

We were pretty much governed by bells. They would be rung late at night and first thing in the morning for the nuns, the first one being at 6 a.m. These bells became a way of life for me. They also corresponded with my need to perform rituals, so I was able to put a lot of my existing obsessive compulsive disorder into the various bells as they sounded. All nuns immediately stopped whatever they were doing at the sound of the bell; even if they had been in the process of dotting an “i”.

At nine a.m., I was called out by a girl in school uniform. She told me her name, and took me to the area of the convent in which the school-aged girls were given lessons. At that point, I was still of the belief that I would find myself at Mount Carmel. But this was not to be the case.

The school room and general area was divided into three rooms. We used one for the classroom, one for sewing, and the other for cooking. Our teacher was Mother Claver, a small but plump nun with a sharp tongue, whose bark was a bit worse than her bite. I was shown some navy skirts, white blouses, and navy sweaters to see which would fit me. I tried as hard as I could to find the right size, but nothing fitted me very well. I was given some white socks and told that I would get a pair of lace-up shoes when my size came in. I was then taken to the room where the cooking was done. Another nun, Mother Philip, was teaching cookery there, so I joined a girl at a table. I felt uncertain about all this as I knew that I was in the wrong color uniform for girls from Mount Carmel. They wore light brown tunics with sky blue blouses.

As I looked around me, I saw, in the distance, what I thought was a long, blue swimming pool. I asked the girl next to me if we were going to swim in it at some point. She looked at me peculiarly, and asked me to repeat myself. The class was silent and everyone was looking at me. I think there were about 15 of us who were of school age. When I repeated myself, I was told, amidst roars of laughter, that that was no pool, and to go and have a proper look. I walked over to the windows, which were huge and took up one entire side of the building. One girl said to me, “Can you see now?” I could see that what I had thought was a pool was actually blue corrugated iron. She asked me if I could see the rolls of barbed wire on top, and I told her that I could. I could also see that the windows through which I was looking were barred; ornate, but barred nonetheless. Someone asked me where the f****** I thought I was. I told her that I was at the Mount Carmel Boarding school for Catholic girls. Huge peals of laughter followed. I was then informed that I was in the “Mag”. I asked what that was, and was told that it was the Magdalene Girls’ Reformatory – otherwise known as Mount Saint Canice. I then asked why there were bars on the window, and was told they were there to prevent us from jumping out, and that the fence was there to ensure that we would not run away. I could not absorb what they were saying, and I suddenly began to feel unwell; I was having an anxiety attack. Mother Phillip guided me into the next room to sit down. I thought that my heart would break. I felt very betrayed and humiliated, and I began to cry. I told Mother Phillip that there had been a mistake made, and that I had been sent to the wrong school. She told me that I had been placed with them by my family, and that I had to stay. I asked her when I could go home, but she told me that it would be some time before I would be allowed to leave. It turned out that it would be eight months before I was allowed a break for Christmas. I can’t describe the turmoil engulfing my mind at that point. The reality was simply too sad for me to contemplate.

My memories of my early days at Mount Saint Canice are not consistently vivid, although I am not sure why. I recall that the first night was exceedingly frightening for me. Due to my extreme anxiety, my face was going numb quite a lot. I had been given a seat at a table with three other people in the refectory – which, by the way, was a new word for me. There were about 200 girls inside. The first thing that I noticed was that they were not all young, and I was puzzled by this. The refectory was divided into three areas, one of which had women who were quite old. It turned out that some of these were the women who ran the convent farm; some were intellectually challenged; and some had been in the convent for most of their lives. I would learn all about this later.

I felt quite uncomfortable as I sat in the dining room. I felt as though everyone was looking at me, and I suppose they were. After all, I was the new girl. I was seated at a table with Judith, the auxiliary nun mentoned abive. These women wore grey habits with grey stockings and black lace-up shoes. They also wore veils with a light blue strip of fabric around the head area, although it was not a full-faced coif like those worn by the other nuns. They also wore light blue and grey belts, and had large silver crucifixes hanging from their necks. These nuns took yearly vows and were usually the product of a lifetime in the institution. While not considered for ‘proper’ orders, they were nonetheless nuns as they saw it; and some, like Judith, were in charge of a group of girls.

Mealtime was unusual. In the afternoon, we had bread with butter and jam, along with cups of tea. Sitting at my table was a young woman who was about 18 to 20 years old. She was profoundly intellectually challenged, and she carried her teddy bear with her at all times. Judith cared for her; in fact, she was like her child. Her name was Kerrie Anne. She could not speak, and was very myopic. I was frightened of her at first because Judith told me that she bit people if she was annoyed.

There was no speaking allowed while eating. I later learned that one could speak if it was the feast day of a saint. Whenever she came into room, the nun on refectory duty would say “God be blessed”, and the room would buzz with chatter. When we finished eating, we washed our cutlery in colored plastic bowls which were bought to the table by the girls whose turn it was to do so. The bowls were filled with hot, soapy water from a large jug, which was also brought to the table. We reset the places, wiped our placemats with a cloth, and dried the cutlery with a tea towel. Our plates were taken away when we were finished. We all took turns at these jobs.

After tea that first afternoon, I went to what was known as a group room. I was allocated to a group called the Rosarians. There were about thirty girls to a group, and we had four groups. The nun in charge of my group was Mother Magdalene. The group room was used for recreation, and had chairs and tables for crafts and puzzles. We also had a TV and various other bits and pieces. We took turns to clean the group room.

On my first night in the dormitory, I recall being very frightened. I had been allocated a bed in a huge room which was shared by about 40 girls. All the women at the home were referred to as girls, regardless of age. I was not able to sleep in the two rooms that the other group members used as they were short of a bed for me; so I slept in the dormitory used by some of the older girls and auxiliary nuns. My bed was in the centre of the room in the middle of a line of beds. I recall the main lights going out as it was my turn to shower. It would have been nine o’clock. My shyness about going to the shower made me late. I was also extremely nervous and I dropped my new shampoo and watched helplessly as it spilled all over the tiles. The bottle, which had the name Blue Clinic on it, was made of glass. I was so upset that I had spilled it. Thankfully someone came to help me to clean it up. I also recall going to bed with wet hair that night. I could still see the moon through the windows. I noticed that these windows were also barred, but I tried not to pay too much attention to this. I cried that night; it was all very, very strange to me. I was also particularly upset because I could not perform my rituals in case I was seen, so I had to do them in my mind. I had developed OCD when I was nine years old and I hade developed a need to perform many rituals as a result of this. My time in Mount Saint Canice made all this considerably worse, as I was constantly anxious.

The curriculum at the school at Mount Saint Canice could have been worse. It covered basic arithmetic, spelling, and the usual subjects up to about grade four level. I recall being annoyed that we had to learn about Burke and Wills. I tended to do my work and say very little. After some weeks, Mother Claver asked me to help some other girls, and I did this throughout the rest of the school year. I was very sad about this, as I knew that I was not learning and the thing that had been so very important to me since I began school, was to absorb myself in my school work. Most of the girls found their schoolwork to be very hard. There was one other girl of my age who was unable to manage her schoolwork. I will refer to her as Lucy, although this is not her real name. Lucy and I became friends and have remained in contact to this day. She had been placed in the home because her parents were heavy drinkers and her mother had thrown her into a fire.

I kept hoping that I would be able to go home to tell my grandmother about all that I was experiencing. My watch had been stolen in the first week, as had my underwear. The latter were, however, replaced by Mother Anselm from the reserves that she had. These clothes were new, but were very old-fashioned; they were made of pink cotton, and the bras were unlike any I had ever seen. I later discovered that they had originally been purchased for the nuns. Long pink petticoats and white ankle socks were the norm. Lucy had come to the home as an emergency placement and had no clothes on arrival, so the pink clothing was not new to her.

During my first week at Mount Saint Canice, my neck was burned. All girls had to be deloused and checked for fleas. I was aghast at the very notion, but had no choice but to go along with it. On my second day, I was given a bottle of vile-smelling liquid by Judith, and told to shower with it. I think this was usually done on the first day, but I had arrived late the previous day. Judith also delegated an older girl to wash my hair with kerosene, and this is what burned my neck. There was also no treatment for this.

We all had to take a glass of Epsom salts once a week. This was to ‘clean us out’ and, in fact, usually gave us diarrhea. We all hated drinking it, but we would lose a mark if we refused. There was also no sense trying to write home about our circumstances, as all our mail was read. This applied to both incoming and outgoing mail. Some girls had to rewrite their letters, while others found pieces cut out of the mail that they received from home and friends. We were allowed to read and write letters on Saturday afternoons in our group rooms, and all letters had to be shown to the group nun.

School ended with a bell at 3 p.m. We filed out in line to the refectory. After having our afternoon tea, we went back to work in our respective places in the laundry until 5 p.m. when we finished work. We were allowed back into the dormitory to have a quick wash before having dinner at 5.30 p.m. As usual, there was no talking, except when we were given permission to do so. The meals, while fattening, were generously proportioned and always warm. I have to give credit here; no one went hungry.

There was even a convent cat to feed. My grandfather had been in the habit of drowning my cats whenever they had kittens. I would come home to find my cat gone and sometimes only one kitten left. I grew to like the convent cat. It belonged to Mother Phillip and I used to amuse Lucy by writing poems about it.

The laundry was huge. There was the ironing room where I worked when I was not in school, the machine room where Lucy worked, the folding and packing room, and the drying rooms. The machine room was very large and contained two enormous mangles and rows of large washing machines. These machines were operated by one man who had been employed by the convent for years. He was unfortunate enough to have his daughter come to the home a year or so later. He was not allowed to speak to her, but they would look at each other from a distance.

The laundry provided services to hospitals and many other institutions. It also offered private laundry services, mainly to the priests, as well as to the archbishop’s residence. To my knowledge, it was the biggest commercial laundry in southern Tasmania. The mangles, which pressed all flat items, were so large that it took two girls to feed a wet sheet into one, and two on the other side to remove and fold it. The heat was so intense that a wet sheet would only need to be fed through once. The work that we did in the ironing room was different, and consisted of tending to smaller items such as underwear, shirts, and hankies. There were dozens of shirts and hundreds of hankies per day. This work was done every weekday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., and girls who were aged over 14 worked on Saturday mornings as well.

I was allocated a place in a new dormitory in time for my 13th birthday. I recall being glad that I could finally see out of a window. Our dormitory was three storeys high, and although my window had bars, I could see the moon and some of lower Sandy Bay, and for this I was immensely grateful. There were nine beds in the room, which was one of the smaller dormitories, and Judith and Kerrie Anne were my roommates. I had a bed, a single locker, a chair, and a mat. Our beds had to be made to army standards, and we had to keep our area clean and tidy. There was an inspection every Saturday afternoon, after which we were given our marks.

Sometimes the girls would try to escape. In fact, on occasion they were successful. But they were invariably caught by the police and brought back to the home. Their hair would be cut roughly within an inch of their scalps, and their fingernails would undergo similarly harsh treatment. “Punishment frocks”, which were dresses made from hessian with bias binding trim, would also be worn for some months. The girls could wear a skivvy under them, but all of their own clothes, with the exception of socks and underwear, were confiscated. These punishment frocks had to be worn to “parlor,” much to the humiliation of the girls. Parlor was the room in which the girls saw their family on the second and fourth Sunday of the month. Some girls who were nearing the end of their sentence would be allowed home for a weekend. This was an extremely special event. In all my time at Mount Saint Canice, I never went to parlor. I had no visitors, with the exception of one visit from relatives from the country who had heard that I was at the home.

There is one particular incident that I will never forget. A group of three girls was planning to escape one Sunday night while the rest of the girls were watching a film. I was in my dormitory helping to bathe Kerrie Anne when they attempted to escape. I had gone to the window to see if I could see them jump. They had planned to jump from the third floor bathroom window – this was one of the few windows that had no bars – to a ledge, to another ledge, and then to the roof of the first floor, which was concrete and had been added on to the home in its later years. The first girl jumped, but lost her footing when attempting to land on the ledge. She kept falling until she landed on the concrete roof. I heard her fall and saw that she lay still. The alarm was sounded by someone and the flood lights came on. An ambulance and the police were called. We soon learnt that the girl had broken her back. We never saw her again. We were told that after being discharged from the hospital, she was sent to Lachlan Park, which was a mental institution. We were all very upset by this. I felt awful because I had known that they were intending to escape, and I repeatedly wondered if perhaps I should have informed one of the nuns. Then again, to do so would have led to a physical thrashing for me and I was afraid of the bullying that took place in the home.

The other girls who wanted to escape from the home would cut themselves or take some other action that would require admission to hospital, as this was seen as preferable to being at the home. One girl who had escaped, been recaptured, and whose hair had been cut off as a result, was working with me in the ironing room one day. Mother Marguerite had gone out for a few minutes. The girl was working on a press for shirts, and I saw her lay her hands on the press as one would do to flatten out a shirt. I then noticed with horror that she let the press down on her hands. I ran to her, thinking that it must have been a terrible accident, and I stepped on the release foot pedal. But this was a mistake as her hands were stuck to the top lid of the press. She screamed, I screamed, and an older girl raced to help us. The burned girl was taken to the hospital and did not return until sometime later. Despite the trauma that I experienced, I was expected to carry on with my work, and to eat my afternoon tea as if nothing had happened. I had nightmares for a long time about the girl who had jumped, and the girl who had burned herself.

I was terrified of the times that I spent as a carer for three girls who had epilepsy. I was terrified of seizures, but was given the job of watching these girls – some of whom were over 21 years old – at night. We slept in a room with nothing but mattresses so that, in the event of a seizure, no one could do themselves any harm. When a girl had a seizure, I had to run from the room – I was given trustee privileges for this – and I had to pull hard on the rope that rang the bell. Mother Marguerite was the convent nurse and, after a time, she would appear with an injection for the girl or girls, as sometimes another girl would have a seizure as well. I was so horrified that I could hardly speak. I would even have anxiety attacks of which they were completely unaware. To say that I lived my life in constant anxiety and fear while in the convent would be an understatement.

There were times of incredible sadness for some of the girls. Sometimes a girl would come to the home pregnant, or another might escape and become pregnant. Although she would try to hide her condition for as long as possible, she was eventually sent to Elim House in West Hobart, which was a Salvation Army home for unwed mothers. The girls eventually came back to us after they had delivered their babies. Some of them were over 18, but remained wards of the state until they were 21 years old. They, therefore, had no say in what happened to them or their babies. To see their sorrow at having lost their children was heartbreaking. To see them punished for what, in hindsight, seems to have been depression was also devastating. Worst of all was the news that one girl had hanged herself, which was such a shock to me that I felt unable to breathe for some time. She had been a lovely person. She had come to the home in the very early stages of pregnancy and had been sent to Elim. She’d come back to tell us that she’d had a baby boy.

On Saturday mornings, we were allowed to sleep in until 7 a.m. We went to a later Mass, had our breakfast, and came back to the dormitories to clean them. We would even wash and polish the floors on our knees. Everything in the convent was always spotless, and we took turns cleaning the bathrooms, which were then inspected.

We were expected to shower every night and again in the morning if we wanted to. Due to my constant efforts to get the kerosene out of my hair, I began to wash it every day, and I have continued this practice to this day.

We worked in our dormitories until lunch time. After lunch, we went to our group room and we were allowed to talk or play a game until Mother Magdalene came, at which point we had other activities to do. Every second Saturday, Mother Anselm would come to the groups as well. She would be told about us and would give us marks and pocket money according to how many marks we had received. I believe that these marks were a way of maintaining some degree of control over the girls. Three marks were to be given to each girl; one for work/school, one for our general care of ourselves and cleanliness, and the other for our general behavior. If we were ‘good’ in all three areas, we received four shillings. If we lost a mark, it would be three shillings. The loss of two marks meant that we got only two shillings, and the loss of all three marks meant that we received no pocket money and no special privileges such as being allowed to go to the movies, which were shown on Sunday nights.

Other forms of punishment took the form of the extra cleaning of the dormitory floors. Used tea leaves were thrown over the floors, which we would then have to sweep and polish. There was a large, red cement hallway that ran through various areas of the home. Scrubbing this hallway while on my hands and knees was a job that I came to know well. It would take me over two hours, and I was expected to use a toothbrush for the grouted areas. I would be given this punishment for simply asking “why?”, or for taking too long in the toilets. They did not consider the fact that I suffered from constipation and that hurrying was, therefore, impossible for me. Furthermore, the red corridor was cold and draughty most of the time.

We always referred to ourselves as slaves, and, looking back, I can see that we were. All the girls who could work, worked long and hard hours, and the sum of four shillings was an insult to them. I had never had any money and was often away in my fantasy world; so it did not occur to me to be less than grateful for anything that came my way that was not going to hurt me. It is hard for me to look back and adequately explain this, but it is how I felt. We were expected to use this money to buy our own toiletries and other items for our personal use. Some girls had parents who provided for them, while others did not. In any case, the nuns took everything that came into the convent and dispensed it as they thought appropriate. Only sanitary pads were provided and we had to ask Mother Marguerite for these. They were known as a packet of “Bunnies” and we were only allowed one packet per menstrual cycle. My periods were heavy and I suffered chapping due to changing napkins infrequently.

We would go up to the dormitories at 7:30 p.m. each week night and lights were out at 9 p.m. I was always excited to get into my bed. I had the most wonderful fantasy life that anyone could imagine and I could not wait to get lost in it. My fantasies were many and varied, but a common theme involved having a large family.

The population of the home consisted of many different girls. There were older girls — women — who no longer worked in the laundry; they would sit outside in one particular corridor where there was sun, in their own group rooms, or perhaps in bed. Some of these girls had not been outside of the home for many years. I knew one older woman who told me she had not been outside for over twenty years. There was another woman in her late thirties whose job it was to care for these girls. As far as I know, this woman had come to the home in her youth, and had never left. Every so often, one of the older women would die, and we were allowed to visit her bed if we wanted to. This was so we could say goodbye to her before she died. I was also terrified of this.

Other girls were younger and suffered from various forms of developmental delay. These girls would often work on the convent farm, which was huge and very productive. They were often overweight, and smelled of cow manure, as I recall. They did not suffer any nonsense from the younger girls. They would clip our ears as we walked past, or hit out at us. Some of these girls had been in the home for as long as they could recall. There was a family of three girls who lived in the home with their mother. I am not sure how this came to be. Then there were the girls who were sent to the home for various so-called crimes — the fallen, the wretched, and the shamed. I have to say that I can’t recall any bad girls at the home. Rather, as I see it, their behavior was the product of being institutionalized. Of course, I did not know any of this then, and I saw myself as bad, and without worth or entitlement.

I have never really recovered from my years of living in Mount Saint Canice. I lived in fear of being locked up again, and maybe, at some levels, I still do. After leaving the home, I went on to make some extremely poor life choices. I was unhappy for most of my life, suffering from profound depression and anxiety. It was not until I was diagnosed with Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in therapy in my late fifties that I began to think and feel like I could actually control my own life. To this day, I believe that someone should be accountable for the tragic occurrences that I witnessed and underwent at that time. When I recall these incidents, I do not believe that any apology given by the government is of any value at for me.

I enjoy a good quality of life now, but I know many women who suffered the same fate in these homes. These women have not been able to lead happy or productive lives. I can only hope that my story will serve to remind people what can happen when children are not cared for or shown the respect and love that they need.

Janice Konstantinidis (nee Exter)

February, 2011

by Rachael Romero (guest author) on 16 February, 2011

Rachael Romero remembers those women, admitted as children, to the Convent of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, ‘The Pines’, Plympton, who had stayed on in the institution well into their adulthood. Why didn’t they leave? What became of them?

Gaylis

copyright Rachael Romero, 1973

Gaylis was a ‘lifer’, a sweet-hearted person left there by her family. She was made to slave in the kitchen with no idea how to be the cook, but she did her best.

I still remember the chunks of lard and the bubbles of powdery flour that had not been stirred together sufficiently before baking a crust for that terrible gravy pie with junks of leathery kidneys swimming in it. I want to retch.

Having once seen ‘Little Jo’ on Bonanza, Gaylis was forever besotted with him – it was all she spoke of. Oh Gaylis what became of you when the place closed and the nuns fled? Slaving was all you knew.

There was also a woman with Downs Syndrome who folded hankies in that thunderous laundry. She waited on a Sunday with her handbag for someone to take her out. No one ever did.

by Rachael Romero (guest author) on 14 February, 2011

Rachael Romero’s artistic talent enabled her to have time away from slaving in the laundry at The Pines. Here is one of the bookmarks that the Sisters of the Good Shepherd asked her to make.

Rachael recalls:

So here’s the rub. When the nuns found out I had talent I was asked to make book marks and cards for them to use.

This way I got out of the laundry for an hour or two a week. What relief they locked me in a room alone to paint!

Peace–quiet!

I feigned a religious conversion in order to escape their radar and plot my escape.

The Sisters of the Good Shepherd ran commercial laundries which serviced many businesses, including hopsitals, hotels and wealthy households. Doing all the unpaid, hard labour in hot conditions were teenage girls who were sent the convent because they were considered to be in ‘moral danger’.

The Good Shepherd laundries operated at the Mt Maria Centre, Mitchelton, Brisbane; Abbotsford Convent, Melbourne; The Pines, Plympton; Leederville, Perth and Mount Saint Canice in Hobart.

Rachael Romero, in 1968, aged 15, was an unpaid labourer in the laundry while resident at The Pines. Below is a laundry slip she kept – one of those used by the Good Shepherd Sisters to charge for their laundry services.

For more information on the commercial laundry services run in Catholic Children’s Homes, see Allan Gill’s 2003 article in the Sydney Morning Herald, Bad girls do the best sheets.

by Rachael Romero (guest author) on 14 February, 2011

Rachael Romero shares the map she drew at the age of 15 while living at the Convent of the Good Shepherd also known as “The Pines”. Rachael’s map includes the site of the laundry where the young female residents worked.

Interestingly, Senator Andrew Murray referred to The Pines in his speech to the federal Senate on 12 March 2008, in which he urged the Australian Government to make an apology to Forgotten Australians and former Child Migrants:

[There] were systemic floggings and beatings with a variety of weapons for the most minor misbehaviours. All these acts amounted to criminal assaults punishable by law at the time. And that is the important point. These things that were done to the children were not lawful at the time and yet there was a conspiracy of silence between churches, health authorities, police and others which mostly kept these incidences under cover.

This appalling treatment of vulnerable kids has its match in prisoner of war camps. Places like Bindoon in Western Australia; Goodwood and The Pines in South Australia; Westbrook in Queensland; Box Hill and Bayswater in Victoria; and Parramatta and Hay in New South Wales were akin to concentration camps that incarcerated and brutalised far too many young people in 20th century Australia. Some beatings even resulted in physical impairments later in life.

by Rachael Romero (guest author) on 10 February, 2011

In her short film In the Shadow of Eden, filmmaker Rachael Romero comes to grips with the physical, sexual and emotional abuse she suffered at the hands of her religion-fixated father while growing up in rural South Australia. The film includes Romero’s memories of her time in the Good Shepherd Sisters’ laundry at The Pines in Plympton, Adelaide.

In the Shadow of Eden premiered at the Yale Center for British Art in September 2003 where it won a Short Film Prize from Film Fest New Haven. Since then it has screened at the Cleveland International Film Festival, the Santa Fe Film Festival, Moondance (where it won the Spirit Award for short documentary) Boulder, Colorado and The Full Frame Documentary Film Festival in Durham, North Carolina where, with the help of The New York Times and a board that includes Martin Scorsese, Jonathan Demme, Ken Burns, and Barbara Kopple it was among six shorts chosen from over 100 ground-breaking documentaries available now on DVD – Full Frame Documentary Shorts, Volume 4, the best of the festival.

Ironically, given all these accolades in the United States, In the Shadow of Eden has been rejected for inclusion in the the Sydney, Adelaide and Victoria Film Festivals.

View In the Shadow of Eden on YouTube.

by Fred Wingrave (guest author) on 6 December, 2010

In this excerpt from Burnside from the Inside 1916 – 1926, Fred Wingrave describes his experience in working in the laundry at Burnside Children’s Home and his affection for Mrs Bunker, one of the women who worked in the laundry.