by Graham Evans (guest author) on 26 March, 2010

The Journey

Here it is – 1958 – my first experience away from home, the big adventure into the wide-open spaces of life itself.

I was seven years old then; it was a glorious day, early morning sun shining brightly through the side window of my Dad’s old Plymouth, the sounds of birds whistling in the trees, and the sweet scent of wild country flowers.

I sat there pondering; it seemed like ages, wondering where this journey was taking me. We drove on when suddenly I realised something was wrong, then Mum said, “We won’t be long, we will pull over and have a picnic lunch”.

We had our lunch, it was by a stream, such beauty I’ve never seen. I suddenly thought, “Where was Dad?” Mum said, “Don’t worry son, you’re just a lad, and one day when you’re big and strong, I’ll tell you of things that went wrong”.

We sat there having this picnic lunch under a tall chestnut tree, I suddenly looked up and there was Mum, staring at me with tears I’d never seen, such beauty and radiance, just like a queen.

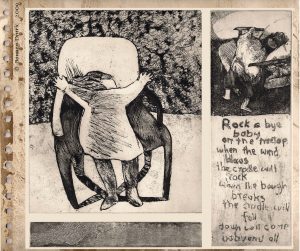

I ran to her side and embraced her tight, when she whispered “Son, it will be all right”. I looked again, and said, “I love you Mum”. She replied, “I hope so, you’re my youngest son”.

I couldn’t stop wondering, “Where was Dad?” It seemed a lifetime and I began to grow sad. So weary my eyes became, I fell asleep.

When I awoke, much to my dismay, we had entered this large school where children played. There were hundreds of them, women in black. My heart told me, I want to go back; to that country town by the dust track, to the place that I loved, to the fields and the trees and most of all to the birds that talked to me.

I stood there so scared and embraced my Mum, when suddenly this woman said, “Come here son, your Mother has to leave on her journey again”. My eyes filled with tears and I started to cry. As she drove off, I heard her say, “I love you son, I’ll be back one day, to take you out in the glorious sun, we’ll have a picnic and have lots of fun”.

As time went by my eyes still filled with tears, here it is now three long years. “I’m never going to see her again”, I said, when Sister Anne called, “It’s time for bed!”

Here is another day, a little schools and lots of play. With the friends that I made, time soon flew by, those tears I cried were deep inside, my heart grew strong, for that place that I loved, the trees, the birds and the stars above, to that country place I once called home, with my Mum and Dad, I was never alone.

As these lonely years rolled over again, I suddenly thought I’m nearly ten, those junior days will soon be gone, to another school, where I had to belong. Four years had gone by, and not once did I see the parents I loved, what was to be.

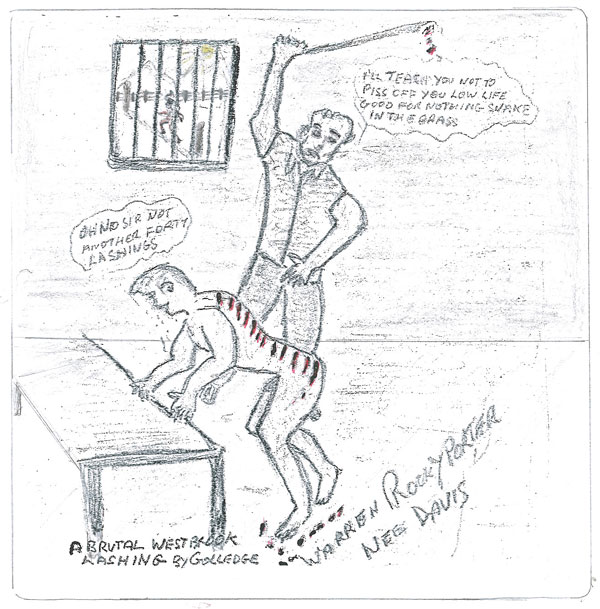

Sister Anne cried out, “Come have a feed”, then it’s off to the new school they called ‘Westmead”. This school was so different, there was no love, do this, come here, and given a shove, bend over and touch your toes, a whack with a stick or a hit on the nose.

Those Brothers I really started to hate, and they had the audacity to call me ‘mate’.

I never learnt much in all those years, but to stand up for your rights and show no tears.

It was not like the Nuns, I was the teacher’s pet and the love they showed, I soon had to forget. In this school, it was do or die, there was moments I remember I had to cry, to myself you see, that’s the way it had to be.

As time went on I joined the band, to do something to forget, if you could understand. The drums I played to my heart was content, I feel this time was worthwhile spent.

At times I wondered why these Brothers were so cruel, there was something not seen, hidden within this school. A brother of mine was expelled, he stood up for his rights, but didn’t tell, we all punished it was like a living hell.

It went on for years, no one could see, for this brother of mine, they punished me. He did not know, for he’d already gone, away from this place, where no one belonged.

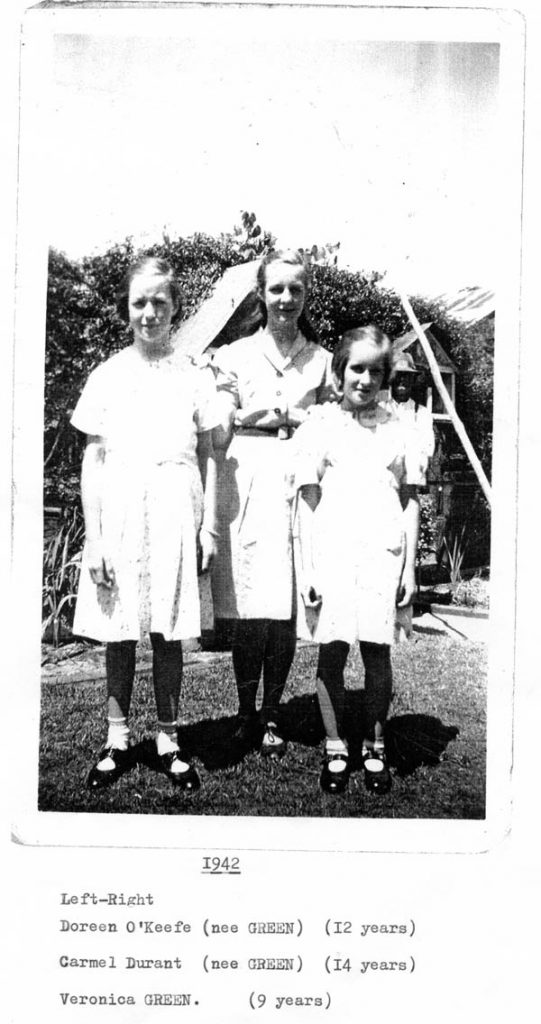

It was 1966, and I loved to run, when all of a sudden this man said, “Son, we’re looking for a child around your size, we’ve been looking for ages, if you can’t realise. His name is Graham, and this is his Mum, if you know him, can you tell son?”

Briefly my heart stopped, much to my dismay. This couldn’t be the woman who put me away. When I turned around she was gone. But I heard her say, she won’t be long. I’ll be away next week, you won’t be alone. I will be back soon, I’m taking you home. Away from this school and their punishing eyes. I’m sorry son I never realised.

I was fourteen when I left and couldn’t look back. The man who spoke to me, his name was Jack. He was to replace the father I never had. I soon became to call him Dad.

As I grew older, we grew apart, but I loved that man with all my heart. He was always there to teach me right, and give me a hug and say goodnight. You know I loved this man called ‘Jack’.

I soon forgot that dusty track, the fields and the tress, and most of all, the birds that talked to me, and the scented breeze.

I went to a new school at Lithgow High, got into some fights, but didn’t cry. They said I was new in town, for this they tried to put me down.

They called me names, but they did not know the troubles I’ve seen down below. I got back up and stood my ground, they tried no more to push me around.

I’m almost twenty-one now and out of play. I got a new job to pay my way. I stayed at Woolies for a couple of years, ‘til I met a girl, who brought me tears.

We all make mistakes, it happened to me. We had a baby and named her Sherie. This woman I love, but it wasn’t to be, a crucial mistake, what is happening to me.

I stayed in touch because I loved the girl, she didn’t want to go out into the great big world. She stayed with her Mum, something I never had, if I took her away, she would only be sad.

So off I went again, to sort out my feelings and get in touch with my brain. I knew I had done wrong, but what could it be, and couldn’t stop thinking of our daughter ‘Sherie’.

Almost twenty-two and I’ve travelled around trying to make ends and settle down. I bought a guitar and I sang around, here and there in these country towns. I was offered a job to pay my way, and this place I thought I’d stay. At least for a while ‘til I got my grips, I played for the love of it and got some tips.

I wrote songs from the heart, you know, and lots of feelings from down below.

I sit here in the loneliness of this room, a vision unveils itself from the gloom. Long red hair, a pretty face, skin as soft as lace. I recognised her instantly. She was a girl so dear to me but she would go and I would know. Yes! She’s gone and left me to the loneliness of this room.

Life goes on, and so must I, it sees the birth of a thousand unwanted lies, but she would stay embedded in my mind, so I could never forget her, and the loneliness of this room. Words like this stuck in my mind, I’d knew I’d forget, but it would take time.

Here it is now nearly December, you know these words I still remember. Now I’m twenty-two and life’s still cruel, I thought: ‘Why did Mum ever choose this school’. I had no friends, they were too far away, no one to talk to and too old to play. What did I do that was so bad, why do I feel empty and sad.

The big twenty-two, it’s a bright new day, I packed my things and on my way. I went back home to Mum and Jack, they were so pleased to see me back.

It was that very night that I had a drink, and I had some more, ‘til I couldn’t think. I started home ‘cause it was so far, in those days I never owned a car, and as I wandered down the lonely road, someone came by in a very slow mode. A cry called out, “Would you like a ride?” I said yes thanks and swallowed my pride. For there was not many people I really knew, you could count them on one hand, there was just a few.

There wasn’t a day that never went by that I didn’t stop and have a cry, or at least a tear, but what could you expect after seven long years. People would say ‘stop’ and ‘don’t be a fool’. I’d like to see them, just one day in that school.

I tried to look back on some good days we had, there wasn’t too many, which was rather sad. We were fostered out on weekends a lot, to different families, whether you liked it or not. I’ll go back to Westmead School and find out why they were so cruel, and why they treated us they like they did, because after all we were only kids. I’d like to see them do it in this day and age, I know you parents would put up a rage.

I’ve seen psychiatrists ‘cause I felt the need, something that was caused by that school ‘Westmead’. I’ve often thought; ‘what was in their mind? To treat us like they did most of the time. What benefit did they really get, to leave us with memories we can’t forget? I am not the only one who is in need, there were lots of us from that school ‘Westmead’.