Graham Budd recalls the influential staff at Northcote Farm School during his residence from 1939: Colonel Heath as a man in the wrong place, “but a man for all that”, old Wally the bootmaker, and Mrs Odgers, with a great affection:

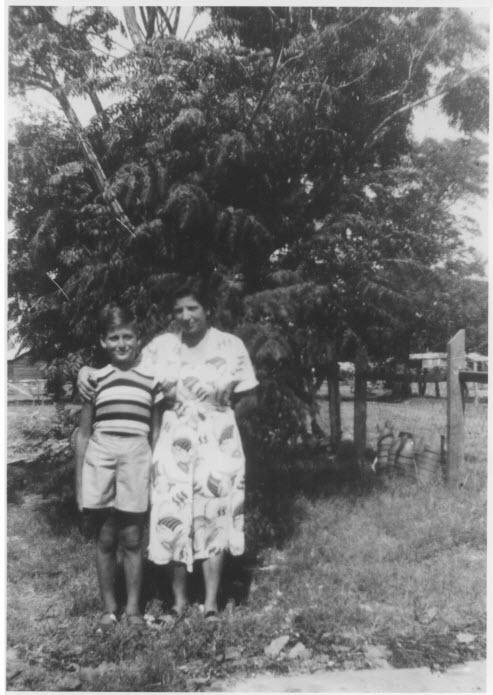

The second personality that concerned me was Mrs Patricia Violet Odgers, nee Herr. My cottage mother. Married an Australian army officer after WWI, they moved onto a bush block at Renmark SA, cleared the block and planted it down for grape vines, he was filling in his time doing odd jobs during that period of time waiting to pick his first crop. No-one knows exactly what happened but he was putting gravel on his driveway using a shovel and a horse and dray. He was found lying on the driveway – the dray had gone over his head.

The settlement commission decided that Violet could not manage the block and that since they had not paid for the block perhaps it would be best to send her back to her parents and give the block to someone else. This is as far as I know what happened. Her father Mr Warren Herr, a well known Melbourne business man, a fine example of the ultimate Victorian gentleman, didn’t want a weeping woman under his feet all day so sent her off on a world tour which lasted quite a long time. While having breakfast in a London hotel one of the quests told her of this strange children’s home in Kensington where young children were collected into groups and sent off to Canada, Australia or South Africa. Violet found it hard to believe so set out to find the place. I remember the day she visited us. Mainly because we got very few visitors and those that did come spent their time talking to the staff and only looked at us kids in the manner of an auctioneer looking over a mob of cattle. Violet did the reverse and spent the day talking to us. She told me years afterwards that she was horrified at what the children said to her that day and decided somebody should do something about them. In the end the penny dropped and she thought, “Why not me?”, a decision that I firmly believed saved me from going barmy.

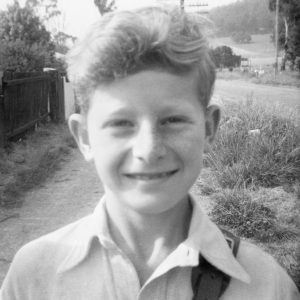

She volunteered to help supervise a gang of 28 boys and girls of whom I was one, being sent to Northcote School, Bacchus Marsh, Victoria. Upon arrival, January 6 1939, she asked Col. Heath for a job. He of course was delighted, Violet being a very different type of person usually found in such places. Well educated, old enough to have experience, in her forties, young enough to keep up with the kids. Obviously wasn’t there because she had to work somewhere and couldn’t get any other type of job, which would describe most of them. She was given No. 12 cottage, 16 boys of whom I was one. A very lonely boy of 11 years. A country boy as opposed to the city breed type, which was the average. Very homesick. Missed my Grandfather, who had opposed very strongly my being sent away. Missed by stepfather a TPI from WWI who had died in March 1938, a man I was strongly attached to. He had been a sergeant in the Coldstream Guards and I adored him. I think that is why I took a different attitude to the Colonel, there was a similarity between them. Mrs Odgers quickly recognised that I wasn’t interested in sports or skylarking as most boys are but I lived in a world of books. She did everything possible to encourage me.

The place was run on a presumption that “an idle boy is a troublesome boy” which is true, but Northcote took it to extreme lengths. The only time we got to ourselves was from 1pm to 5pm on a Sunday. A period spent wandering all that area between the Werribee Gorge and the Brisbane ranges. Sometimes even wandering as far as Bacchus Marsh, a distance of a very hilly 7-8 miles by the shortest but hardest route. It was of course a region considered “out of bounds” and beyond all the youngest of us. The rest of the week was rise, 7am cold shower, do whatever work you were rostered for after making your bed military style. The work would be half an hour of housework, then 20 minutes physical exercise down near the central dining room, run by the Colonel himself. Then community breakfast, plate of porridge with milk but no sugar, two rounds of bread and dripping, one glass of milk. Back to cottage on the double, nobody ever strolled. Finish whatever you started before the physical jerks session, collect school books, homework, etc. and off to the state school, a half mile down the road. At 12 pm back to dining room dinner, mutton stew with rice and tapioca, alternate days except Sunday when it was dried apricots and custard. 1pm back to school. 3 pm hurry home put school books away in your personal locker, which contained just about nothing else, bags etc. were unknown. Out at the run where the Colonel stood blowing his whistle. Then all working together under his watchful eye planting trees, digging drains, digging gardens, building a tennis court, cleaning drains, etc., etc. After which, back to the cottage evening meal at 5pm. Two rounds bread and dripping, two rounds bread and jam, melon and lemon – I cannot remember anything else. One glass of milk. At this meal we were permitted to talk at the other two, silence was the rule. But in your cottage we all listened to The Argonauts children’s session on Mrs Odgers’ wireless. I think it was actually given to us by her father. The meals never varied the three years I was there as far as I remember.

Mrs Odgers received the newspaper The Argus sent in the mail each day and she contrived to see that I had time to read it each day. I was the only one that received this luxury. The evenings were spent attending scouts, boxing lessons run by the Colonel, farm lectures from the farm manager – we had 3600 acres. Choir practice, Mrs Odgers was the organist, or anything else anyone could think up to keep us occupied. 8 pm bed. The beds were army style cots, no glass in the windows just fly wire with a canvas blind that was not allowed to be lowered unless it was actually raining. No talking in bed. That was that. We had to write home once a month. I discovered years later that they did not receive a single letter neither did I receive a single reply. What happened to our letters is anyone’s guess.

After leaving 8th grade, moved to No 8 cottage where 14 boys were kept to provide weekly labour working in the kitchen, the Colonel’s personal garden, the bootmakers staff dining room, laundry etc. etc. A year at that then moved down to the farm a quarter mile away in opposite direction to the state school. Then we milked 100 cows. Northcote is listed in dept agriculture records as one of only two dairies that milked over 100 cows in 1938/39 in Victoria. Worked a large piggery, several hundred pigs. , a chicken farm, grew all our own vegetables and killed six sheep a week, hence the mutton stew. The 20 biggest boys did all that sort of work, aged 14 to 16 years, all living in what was known as the Bunkhouse with a married couple in charge. These boys were paid 6d per week. The younger ones were paid 2d, 1d must be put in Sunday’s church plate. Boy-girl relationships were strictly taboo. A rule which concerned me seriously as Dorothy Barber was my best friend. Much effort was put into keeping us apart. A thing we both strongly objected to. Mrs Odgers came to the rescue after I left her cottage by occasionally invited the two of us to her cottage for Sunday night’s tea, not sure the Colonel was game to take her to task for it. I eventually married her. We had nine children, not having a family of her own, Dorothy was determined to create one. Looking back I think we overdid it a bit, but Dorothy was happy. Unfortunately she died in 1976 in a road accident and took our youngest daughter with her. I have never forgotten her.

This gives something of the skeleton of our lives. It of course, raises many questions but Northcote’s main faults if one can call it that was total lack of personal relationships with anybody. Unless you were lucky enough to have a brother or sister then the feeling of being deserted by the world was very strong. Mrs Odgers realised that. It was perhaps the thing that differentiated her from the run of the mill staff. The fierce, physical punishment dished out to some of the boys was criminal to say the least. But that was the standard old fashioned army way. But we were children, and children who had many hurdles in life to jump over at that. I never received any such treatment at the hands of the Colonel, in fact, I got along well with him, but I witnessed many of his sins which horrified me, especially as no-one ever bothered to tell us what the victim had actually done. Neither did I ever witness or knew about any sexual crimes, rumours of which surface now and again. But Dorothy did fill me in about things like that many years later. So they did happen. Twice, however, I was physically bullied by adult men on the staff and once threatened by a school teacher in the staff dining room when working as a waiter there. She demanded I serve her first as she had to get back to school.

I replied, “So do several people”.

She jumped to her feet and threatened me.

Old Wally the bootmaker spun around in his seat and glared at her and said, “You touch that boy and I’ll box your ears until they fall off. If you’re in such a goddam hurry, why don’t you go get it yourself? No-one is stopping you!”, a speech that forever fixed him in my memory.

by Graham Budd, February 2011.