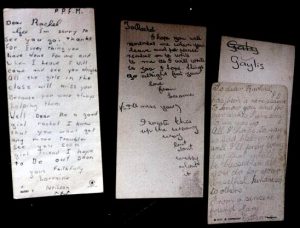

Dr Wayne Chamley, an advocate from Broken Rites, shares the history of Tony Danis. Tony was held in the Mont Park Asylum after escaping from a home run by the brothers of St. John of God. Wayne did a lot of advocacy work for Tony and he now lives comfortably.

Tony Danis’ experience at a Home, in Victoria, run by the brothers of St. John of God:

I was born in 1946. I live alone. Since about the age of 16 years I have been able to work sometimes, in either full time or part-time work to support myself. I have worked in a range of manual jobs. At other times I have had to live on social security while experiencing serious depression. For most of my life I have suffered seriously from asthma and this has been getting progressively worse in recent over the last six years or so. At the beginning of this year I had to finish working because of this illness and ongoing depression.

Records that I have obtained about my childhood indicate that I was first placed into care in St Anthony’s and St Joseph Boys Home at the same time. We were later moved to a Home for Boys … that was operated by the St John of God Brothers. At times I was taken for holidays to the St John of God farm … and also to a house that the Brothers had …

Placement in [VIC] Institutions

- St. Anthony’s Home: 1950 to 1951

- St Joseph’s Home: 1951 & 1952

- St John of God Home: 1952 to 1960

Domestic Routine

As I recall, the domestic routine … as fairly constant. I was in an upstairs dormitory and as I recall all of the boys who slept upstairs were the ones who either never, or rarely, had adults visit on weekends. The boys who got visitors were on the ground floor.

Every day boys were woken early, they then dressed and went to the dining room for breakfast. After meals some boys were rostered to clear the tables, sweep the floors and help with dishwashing. Boys not rostered were allowed to go outside and play. Later a bell went and boys went into classes.

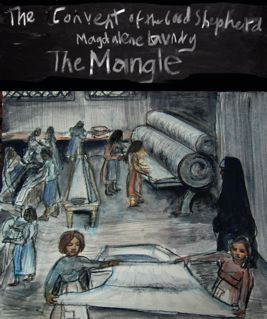

While many of the boys went to classes for most of the day, I only went to short classes in the morning. After this I was put onto other duties. These varied and included gardening, maintenance jobs, working in the kitchen after lunch and helping to prepare vegetables for the evening meal, cleaning the dormitories and making beds.

After school classes had finished we were allowed to play outside and then we would come in for tea. All boys had showers either before or immediately after tea and showers were supervised by the brothers.

After dinner, boys were allowed to watch TV until about 8.30 pm at which time they had to go to bed. Before going to bed, many boys upstairs were given a red medicine every night. This made me feel very groggy.

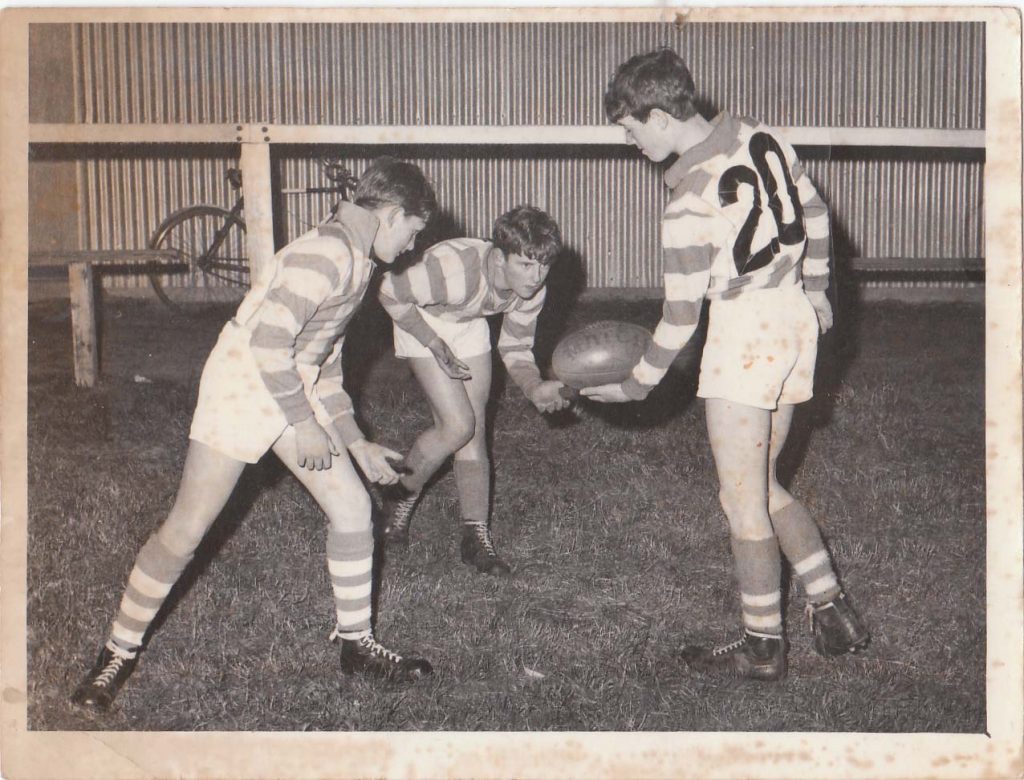

On weekends, boys were allowed to play various games and sometimes we were taken by brothers to a football match. Sometimes the brothers would get very drunk while we were at the football.

Experience of Abuse

I experienced severe and sustained abuse which was carried out by several of the brothers when I was in the Home … and at the … Farm and in the house …

I experienced the following abuses

- Sexual abuse

- Physical abuse

- Starvation

- False imprisonment

- Incarceration in a psychiatric institution sat the instigation of the brothers

- Deprived of an education and subjected to unpaid child labour

Sexual abuse

During my nine years (approximately) in the Home … I was sexually abused many times and by several of the brothers. I also experienced instances of harsh physical abuse. The sexual abuse varied from fondling by one and sometimes more brothers and it took place when I was in the toilets and during the night when I was in the dormitory. Over a period of 3-4 years I was abused frequently by five brothers.

On another occasion I was raped … by Brother F. in a toilet. All the time I was crying and in a lot of pain.

On another occasion when I was about 10 years old, I was held down by three brothers in the corridor of the dormitory and, while one continued to hold me on the floor, the others manually pulled out some emerging pubic hair and chest hair. As they did this, they joked and referred to my having “bum fluff” which had to be removed.

The sexual activities of the religious brothers were not confined to within the precincts of…[the Home]. On occasions boys were taken from Cheltenham for holidays. In my own case I was taken for holidays to the farm and to a holiday house.

The two brothers at the holiday house were Bro. H and Bro M. Both these brothers abused me and I was also abused by a Bro. B while I was at the farm.

Physical abuse

From the time I was placed into ‘care’ … I experienced physical abuse at the hands of various brothers and I lived in fear. I was not the only boy who was treated like this although I did seem to be singled out, on several occasions, for particular punishments. The abuse took the form being punched in the body and/or hit on the side or the back of the head. On other occasions I was beaten by an individual brother using a piece of cane and at times I was whipped by a brother using a leather strap.

Many times I received a beating when I arrived late at the breakfast room along with another boy, L. who had red hair. The circumstance that led to my often being late for breakfast is linked to the fact the L. and shared the same dormitory. Each morning L. had to put calipers on his legs on order to be able to walk and if L. was slow in getting ready, I would stay in the dormitory and help him to put on his calipers. Thus I was often punished for helping my friend L. while L. himself was punished for being late because of his having a physical disability. Another boy who was often punished for being late was L. W.

Starvation

Hunger was a constant companion while I was in the ‘care’ of the brothers. This reflected the fact that the amount of food made available to boys was insufficient and often the meals lacked any variety. Consequently, sometimes boys did not eat a meal then our hunger got worse.

When boys are staying at Lilydale we were allowed to help with some of the farm work including milking cows and feeding chicken and pigs. The pig’s feed included leftovers from the kitchens and this was transported to the piggery on a truck or a trailer. I can recall occasions when I and other boys would ride on the same vehicle going to the piggery and we would eat the best of the scraps before they were fed to the pigs.

False imprisonment

On one occasion when I was about 11 years old, I was whipped very heavily by a brother using a leather strap. Because the assault upon me and the pain that I was experiencing, I could not stop crying and so I was then locked in a dark room and left there for three days. Every now and again I was checked by a brother and during those days I received only bread and water.

When I was let out of the dark room I was crying and very upset. I learned that while I had been locked up, all of the boys had been given new leather scout belts. Later that evening, Bro. T. came to see me in the dormitory. He had brought me a new scout belt and the buckle had my own name on it. Bro. T. was a very kind person. Although he knew about the abuse that was going on, because boys told him, he did nothing about it.

This experience of being locked in a small dark room has had a profound effect upon me and to this day I experience uncomfortable anxiety if I am in a dark room and the door is closed.

Incarceration in the psychiatric institution at Mont Park

At the instigation of the Brothers of St. John of God, I was incarcerated in the Mont Park Asylum for more than two years.

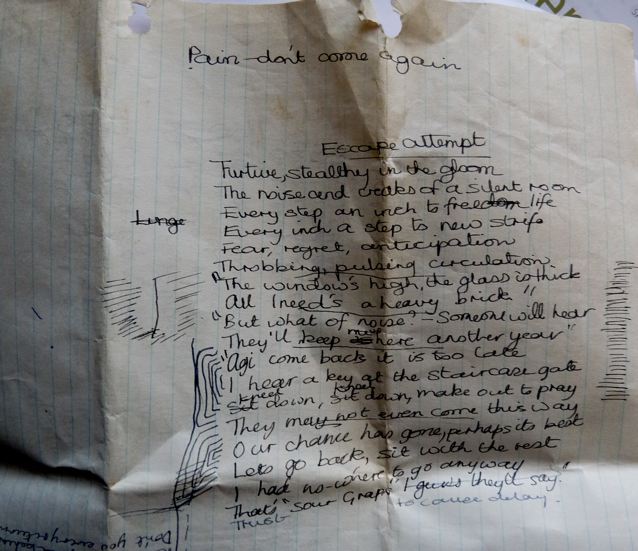

The circumstances that led to my being incarcerated need to be explained. When I was 12 years of age I ran away from the Home on three separate occasions. My motivation each time was to try to escape from the abuse, the terrifying experiences, the persecution and regular beatings that I was getting at the Home. The sequel to each escape was for me to be returned to [the Home] and then I was punished for my action. Usually this took the form of further beatings by various brothers.

In one escape I managed to get to the Royal Botanical gardens and I entered the back of Government House. One of the gardeners met me and I was taken to a kitchen at the back of the large house. After a short time the wife of the Governor came and talked to me. She arranged for me to be washed and given food and I told her about being whipped and abused by the brothers. Her response was that I was making the story up. Soon after, a police car arrived and I was taken to a police station close by and I was questioned about my escape. After this I was driven back to [the Home] in a police car in the company of female police.

After my third escape I was sent away from [the Home] by the brothers and I was placed into a receiving house at Mount Park Asylum. This was a terrifying experience. I was first placed in unit M10 which was like a prison. During the day I was allowed to move around within large communal rooms and I could watch TV. As I was fairly small and only a young teenager (13 years old), I was sometimes physically attacked by some of the older patients with mental illnesses. I was not allowed out of the unit unless I was accompanied by a member of staff.

During the night I was locked up in a small cell that had bars on a window and a solid door with a small, barred, glass window in it.

I spent about two years at Mont Park until one day a Dr R. had a long talk to me. I recall this doctor made an assessment of me and then told me that I should not be in such a place. I was 14 years of age.

After my meeting with this doctor, arrangements were made for me to live in a private house in Preston where one of the nurses lived. After a short time I got a job in a local clothing factory and I continued to board at the house for a few years.

Deprived of getting a basic education and subjection to unpaid child labour

As I have outlined in the section that describes the domestic routine at [the Home], I was given little opportunity to get a formal education. This was not the case for other boys who spent several hours each day in school classes. The chance to learn to read and write was denied me by the brothers and instead I was kept in a situation of unpaid child labour. For most of the time at [the Home], I was required to do domestic work for the brothers.