by Freda Briggs (guest author) on 26 March, 2010

Ninety-three percent of 4007 self-confessed child molesters claimed to be religious (Abel & Harlow, 2001, p39).

Predators in the Roman Catholic Church

It is now recognised that the sexual abuse of children by Roman Catholic clergy and monks is neither a new problem nor is it caused by ‘celibacy’; it has an extraordinary long history that goes back 2000 years as shown by Dominican priest Father Thomas Doyle, and two former Benedictines, celibacy historian A.W.R Sipe and theologian and canon law expert Patrick Wall in their meticulously researched book, Sex Priests and Secret Codes (2006) . They show that the Venerable Bede, (AD 672/3-735) decreed that clergy who committed sodomy with children should be given increasingly severe penances commensurate with their rank. Laymen would be ex-communicated and made to fast for three years while deacons, priests and bishops had to fast for seven, ten and twelve years respectively (p19). In the 12th and 13th centuries, the crime was labeled as sacrilege, then heresy. Penalties became harsher, including fines, castration, exile and even death. Accused clergy were dealt with by church courts then handed to secular jurisdictions for further punishment. That did not stop the crimes.

Celibacy was discussed from the C4th but only in the Western church. It wasn’t imposed until the second Lateran Council in 1139. One of the explanations presented for the introduction of celibacy was to prevent widows from inheriting church resources.

The introduction of celibacy removed legitimate outlets for sexual release and child abuse continued despite the threat of severe consequences. Reformers such as Martin Luther (1483–1546) and John Calvin (1509 –1564) rejected celibacy given that they could see no biblical or theological justification for it and there was widespread evidence that clergy were hypocritical sinners who violated their vows with men and young boys.

When face-to-face private confessionals were introduced, priests were allowed to hold them in their own homes. They were also given the authority to determine what constituted a sin. This increased the power that sex offenders needed to use young people for sex. Victims were threatened that they would not receive absolution if they were not compliant. It seems that they were afraid of the threat even more than they were afraid of being raped given the church’s teaching that without absolution they would go to everlasting purgatory. An additional hazard was that if victims reported the priest for abuse, they risked being accused of ‘false denunciation’ resulting in ex-communication and that, in turn, would send them to hell. The threat of ex-communication is still used by the Roman Catholic church to control the masses.

On May 30th 2008 it was reported that the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano proclaimed that the Pope would automatically ex-communicate bishops and anyone who attended or was involved in the Ordination of women. This was meant to control and silence, through fear, the growing number of Catholics who favour women being admitted to the priesthood.

The culture of ‘blame the victim’ evolved as priests became more powerful. The Code of Canon Law 982 contained a canon stipulating that if victims confessed to being sexually abused by priests, the penitents were not to be absolved of sin until a retraction had been made and ‘damages repaired’. This code did not suggest that the priests who coerced and blackmailed parishioners to provide sex should be punished.

Doyle and colleagues claim that, in 2000 years all that changed about child sexual abuse by clergy and monks was the emphasis on secrecy to protect the church hierarchy. They show that this began in earnest in the Vatican in 1922. In 1962, church legislation gave bishops the right to process cases of sex crimes committed by clergy. All those involved, including victims and witnesses, were committed to total and perpetual silence with automatic excommunication if they revealed the abuse to other authorities.

On April 24th 2005, The British newspaper The Observer reported that the Pope was facing allegations that, as Cardinal Ratzinger, he ‘obstructed justice’ by issuing an order to ensure that the church’s investigations into child sex abuse claims be carried out in secret. The order was said to have been sent in a confidential letter to every Catholic bishop by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. The letter extended the church’s jurisdiction and control over sex crimes. It was said to have been co-signed by Archbishop Bertone who, in 2003, said that the expectation that a bishop should contact police to report a priest who confessed to paedophilia was unfounded.

The letter allegedly stated that the church can claim jurisdiction in cases where abuse has been ‘perpetrated with a minor by a cleric’ and the church’s jurisdiction ‘begins to run from the day when the minor has completed the 18th year of age’ and lasts for 10 years. Ratzinger ordered that ‘preliminary investigations’ into any claims of abuse should be sent to his office, which has the option of referring them back to private tribunals in which the ‘functions of judge, promoter of justice, notary and legal representative can validly be performed for these cases only by priests’. ‘Cases of this kind are subject to the pontifical secret’ Breaching the pontifical secret at any time while the 10-year jurisdiction order is operating carries penalties that include excommunication. A lawyer acting for American victims criticised the letter. He said, ‘They are imposing procedures and secrecy on these cases. If law enforcement agencies find out about the case, they can deal with it. But you can’t investigate a case if you never find out about it. If you can manage to keep it secret for 18 years plus 10 the priest will get away with it’.

It is ironic that six months previously, Pope John Paul stated publicly that the church was seeking open and just procedures to respond to complaints of sexual abuse and was committed to compassionate and effective care for victims, their families and communities. This was obviously not taken seriously given that a year later, the Dean of Canon law stated that church leaders should resolve abuse cases themselves without involving police.

Roman Catholic predators in Canada

In the meantime vast numbers of allegations were made public in Canada. On January 12th, 1988, Father James Hickey pleaded guilty to twenty counts of sexual abuse against boys in the various towns where he served as a parish priest over an 18-year period. In the following year, several other clergy were charged. For generations there was an unwritten rule that crimes involving Catholic clergy were dealt with by bishops but when Hickey’s crimes appeared in the news day after day, more victims found the courage to speak out. The church’s response was described as one of ‘self-interested chicanery’ with no concern at all for the victims. As time went on it became increasingly obvious that bishops knew what was happening and had ignored many sexual crimes committed by clergy. This fuelled the anger of the community .

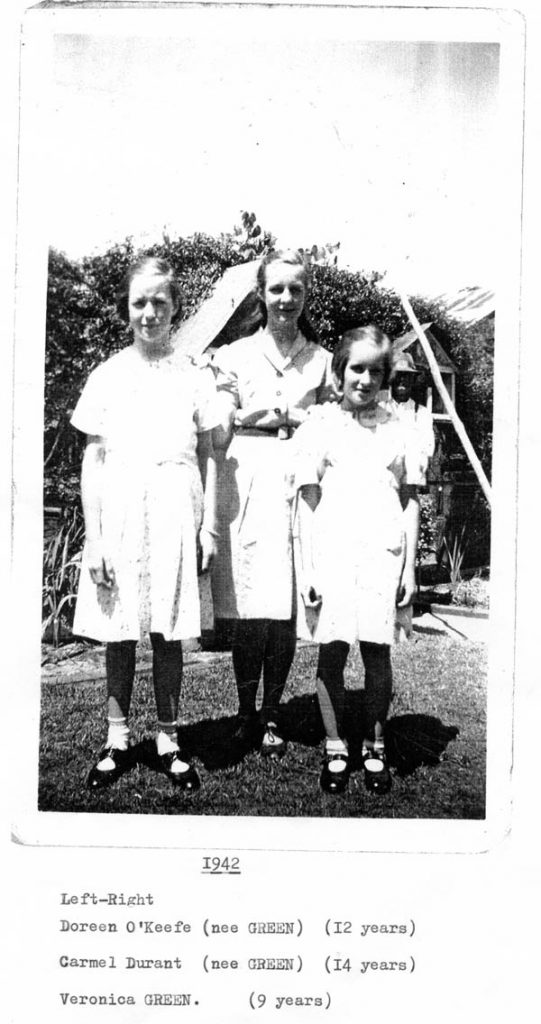

In 1989, the Christian Brothers Mount Cashel Orphanage in St John’s, Newfoundland, was the subject of a state investigation (the Hughes Inquiry) over claims of severe physical and sexual abuse stretching back over decades. In 1975, detectives ‘bucked the system’ to uncover the abuse of the ninety-one young residents but higher authorities terminated their investigations and tried to have the words ‘sexual abuse’ removed from reports. Concerned adults who reported to police were allegedly shown the door with ‘How dare you make up such allegations about the good Brothers’. Fourteen years later, a clergy abuse survivor named Shane Earle called the newspaper office and met journalist Michael Harris. Shane was the first of many victims of the Christian Brothers’ Orphanage to go public. There was such an outcry that the state had little choice but to establish a Royal Commission.

The Hughes Commission proceedings became prime-time viewing throughout Canada. They laid bare a shining example of collective indifference, hypocrisy and failure of the police, judiciary, church and social services to protect the interests of hopelessly vulnerable children. It was revealed that over a 14-year period, 87 persons in positions of power had learned of the happenings at Mount Cashel and did nothing to stop the abuse of boys. Was this because these children, being without parents, were viewed as less than human or was it because, if their claims were taken seriously the state would have had to find alternative, more expensive accommodation; or was it because no one wanted to upset the monks who were held in high regard because they took in disadvantaged children?

In 1990, Harris published Unholy Orders, a best-selling detailed account of the widespread abuse and scandalous cover-ups of criminal behaviour by the Catholic Church and state government. Civil and criminal proceedings followed and 26 priests and Brothers were convicted of sex offences against children in Newfoundland alone, nine of them associated with Mount Cashel Orphanage. The Archbishop resigned and, over time, the provincial government arranged an out-of-court, $18C million settlement for victims and tried to recoup the money from the Brothers.

Roman Catholic predators in the USA

In the US, Catholic dioceses have paid millions of dollars in compensation settlements and some went bankrupt as a result of child sex abuse being covered up by bishops who simply moved accused priests to other parishes where they abused more children. It was reported that some dioceses had to sell schools in poor areas to pay compensation bills and even the poorest of parishioners were asked to contribute to the costs of the defence of clergy and contribute to the compensation bill.

It was reported that 600 children were known to have been abused during the period when Boston’s now notorious Cardinal Bernard Law was in office. He resolved the problem by moving paedophiles to other parishes. He allegedly assured concerned parents that these same priests had unblemished records. Although the Archdiocese closed 65 parishes before Cardinal Law stepped down, his name became synonymous with the nationwide church scandal. Law resigned on December 13th 2002. He moved out of the $20 million three-storey house and initially took a lowly position with Sisters of Mercy. In 2004 victims were further angered when Pope John Paul rewarded Law with a prestigious appointment in Rome which provided its previous incumbent with a salary of US$12,000 a month. In addition to a long interview on ABC news and lots of photo opportunities, Law was invited to a US Embassy reception for President and Mrs Bush. He was even selected for a role at Pope John Paul II’s funeral. According to a report in the New York Times, when asked whether his concealment of child sex offences entered into the decision to give him new visibility, the Vatican spokesperson said: “I don’t think so.” Cardinal Law is now said to live in opulent surroundings far from unpleasant reminders of his past transgressions. Given the cost of compensation to victims, his successor in Boston had to be satisfied with more modest quarters. Those representing the victims of abuse tolerated by the Cardinal concluded that the Vatican either doesn’t understand the problem of clergy sex abuse or the damage inflicted on victims’ lives, or it simply doesn’t care.

Religious predators in Australia

In 1993–94, Briggs, Hawkins and Williams researched with 198 self-selected male victims of child sex abuse including 84 convicted sex offenders in seven Correctional Centres in Western Australia, New South Wales and South Australia. We asked them how old they were when they had their first sexual experience and overall 15% revealed that they were abused by Catholic priests. In the case of prisoners abused by religious figures when they were aged 11–15 years, one third said they were abused by house-masters in Christian Brothers’ schools and 17% by Catholic priests. In the group of men who had no convictions for sex offending, 29% of those abused between the ages of 11 and 15 years claimed to have been used for sex by Catholic priests, 10% by Christian Brothers, 10% by church youth leaders and 10% by clergy in other denominations. In other words, 59% of the 11–15 year old boys who were abused were the victims of religious figures. Prisoners were 23% more likely than non-offenders to have been abused by monks in school settings.

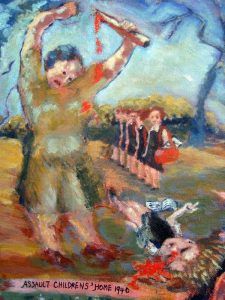

All those abused in institutions regarded the sex as one comparatively minor aspect of a totally violent and damaging environment that exposed boys to emotional and spiritual abuse, sadism, bestiality, violent and senseless punishments and a continuous process of dehumanisation. When this finding was published with sensationalist headlines a year later in The Australian, the Archbishop of Sydney’s media secretary Fr Brian Lewis told the media that he had conducted his own investigation and found that the researchers’ methodology was unscientific and only Roman Catholic subjects had been interviewed. This was a classic case of ‘dismiss the message and shoot the messengers’. First, it was physically impossible for Father Lewis to have checked out the subjects in three states between the arrival of his newspaper and going to air a few hours later given that interviews were one-hundred-percent anonymous and prisoners were interviewed when they were about to be released. Second, Father Lewis had clearly not read the report published a year earlier by the Australian Institute of Criminology (Criminology Research Council (CRC)) in July 2004 or he would have known that only 21% of subjects interviewed claimed to be Roman Catholics. Third, to receive CRC funding, the methodology obviously had to be approved not only by the university’s ethics committee but by Correctional Services in three states.

Fr Doyle et al (2006) noted that lying by Catholic clergy is supported if it is to protect the institution of the church.

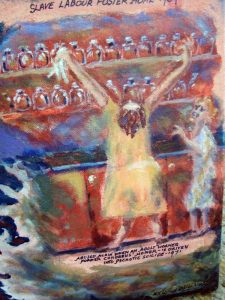

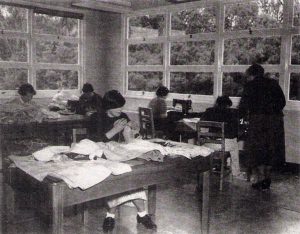

Boarders in West Australian Christian Brothers schools said they were sexually abused from their day of arrival by both housemasters and older boys who, as a rite of passage, were required to become abusers at the age of twelve for the sexual and sadistic pleasure of the monks . Having served their apprenticeship as victims from age 5–12 years, they were required to sexually abuse younger children. In some boarding schools where there were farm animals, monks engaged in bestiality. Not surprisingly, we learned that brothers and priests recruited victims for the brotherhood and priesthood, thus ensuring that child abuse became inter-generational. At the age of eighteen, residents had no experience of relating to the opposite sex or the outside world and remaining in the organisation became an easy option. Some victims said that, after they left boarding school, they were shocked and disgusted to learn about heterosexual sex.

Western Australia’s Christian Brothers’ victims said that abuse was confined to residents who had no visitors. Day boys seemed to have been unharmed and, of course, they supported the Brothers when their crimes were eventually revealed.

The greatest confusion was experienced by boys who were subjected to appalling acts of sexual and physical violence and degradation in the name of God. Victims also carried a great deal of guilt because they experienced jealousy when they saw monks picking up other children from their beds to take to their offices for sex. Although they hated what happened, they said this was the only time they could please the monks and the boys were desperate for approval given that at other times they were beaten with belts with crucifixes until they bled. Some had elastic bands tied tightly around their penises overnight as a punishment for bed-wetting. This practice caused great pain and embarrassment. As adults they continued to suffer from flashbacks, low self-esteem, night-fears, nightmares, mental and physical ill health, depression, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, feelings of inadequacy and self-destruction. Some could not cope with tenderness or being touched and some became (convicted) child sex offenders.

Only 26 of the 198 Australian male victims interviewed by Briggs et al tried to report one of 1700 offenders. Only one succeeded. The parents reported a priest to a senior clergyman and, typically, the priest was sent to a retreat for a few months then moved to another parish. The remaining mothers disbelieved their sons and punished them for dirty talk. A trusted grandma told her grandson that God would rip off the victim’s arms and legs if he told anyone about what the priest had done. When a West Australian social worker reported the Christian Brothers to senior police, she received the same treatment as her Canadian counterparts. State wards in boarding schools were trapped and had no one to tell. A boy in a Catholic College confided in a friend and learned that he, too, was a victim. They reported this together but no action was taken.

On rare occasions, Brothers were moved to other schools in Western Australia then South Australia where they allegedly continued to abuse boys. If bishops knew that child sex offending is lifelong habitual behaviour, they ignored it. More recently, instead of sending them interstate, some have been sent to work with disadvantaged children in Papua New Guinea, Cambodia and developing countries where justice systems can sometimes be manipulated.

Christian Brothers were not the only Australian monks involved in hiding sex crimes. Court reports show that Marists allowed one of their Canberra teachers to continue teaching long after they knew that he was a sex offender. Documents tendered in court revealed that a teacher and one headmaster were told by victims that Brother Kostka had molested them, but the school allowed him to teach for many more years. One alleged victim told police that he reported Kostka because he was concerned that the monk was spending a lot of time with another young boy. He said he was told the next day that “nothing was going to be done regarding his allegation and concerns”. The victim said he returned to the school several years later and told the then-headmaster of the assault. Court reports show that the headmaster challenged the offender who denied the crime and the matter was passed on to Kostka’s “superiors”, not police. The alleged victim was so intent on preventing Kostka from re-offending that he met a senior Marist, Brother Alexis Turton, who became professional standards officer for the organisation. The witness said he was asked “what he wanted” from the Brothers, and was offered counselling. Brother Turton later informed him that Kostka had retired to the Marist’s Mittagong farmhouse. The alleged victim’s brother visited the farmhouse and found Kostka running a drop-in centre for boys. Victims told police he won their trust and confidence before developing a pattern of systemic abuse, some boys being molested on a daily basis. He would often put his hands down boys’ pants while other students were in the room. At other times, he exposed himself and forced boys to touch his genitals. One victim, who was molested in the school cinema, told his parents who, instead of reporting to police, told the headmaster. He is said to have offered to handle the matter “in-house” and Kostka taught for another seven years. Another victim, to whom six of the admitted eleven offences relate, said Kostka abused him for three years “almost daily” and sometimes in the classroom while other students were present. In turn, Kostka “showered him with kindness”. On one occasion, the teacher threatened another victim with expulsion if he told anyone. Kostka’s offences are also the subject of a civil claim for compensation. He pleaded guilty to offences committed in both his office and residence.

Patterns in offending

The sexual abuse of children by Catholic clergy and monks follows set patterns:

- The priest is perceived as God’s representative on earth which places him in a uniquely powerful position, causing immense fear and confusion for the victim.

- The child is powerless and under tremendous pressure to keep the abuse secret.

- The child gains the impression that the abuse is his or her own fault and s/he is bad.

- Abusers choose compliant children whose parents are devoted to their church and are unlikely to believe complaints or report to police.

- When abuse has been revealed to church administrators, their response has seldom been responsible and sensitive to victims.

- The parents’ trust in the bishop makes way for manipulation, intimidation and even deceit leading to further damage to children.

- A community that is uninformed about child sex abuse supports offending clergy and church leaders and denigrates victims.

Naïve, trusting parents have allowed priests to occupy the same room and even the same bed as their sons when they’ve had too much whisky. Parents were flattered when priests chose their children to be altar boys. They were prouder still when their sons were chosen to accompany priests on outings to other parishes or have sleep-overs in seminaries . Parents did not listen when the boys said they didn’t want to go. Some hoped that the priests’ attention might lead to their children choosing a religious vocation. Others hoped it would provide them with a place in heaven.

Such is the power of the church that when parents in Adelaide and rural Victoria reported priests and monks for sex offences against their sons, the families were ostracised by their Catholic communities and they, not the offenders, were deemed to have brought the church into disrepute. Despite the publicity given to reports of child sex abuse, the idea that clergy can harm children is completely alien to those responsible for their safety, The author was present when a priest walked into a Catholic school at lunchtime, saw a group of eight year old boys in the corridor and asked them if they would like to go to McDonalds. He opened the staff-room door, called out that he was taking kids for Big Macs and away they went. Staff said, ‘Isn’t he cute’. When the author asked whether he had parents’ permission to remove children unsupervised and whether he was insured in case of an accident, the principal said she should conduct her research elsewhere.

Protestant predators

The author was co-author of the Inquiry into the Handling of Child Sex Abuse Cases by the Diocese of Brisbane and the then Governor-General Peter Hollingworth in his capacity as Archbishop. In addition, she acted as consultant to lawyers and professional witness for very large numbers of boys who were abused by clergy and teachers while attending elite church schools in Adelaide and Queensland. All except two cases involved the abuse of boys. We know from Abel and Harlow’s (2001) research with 4007 child sex offenders that men who abuse boys start at a younger age and abuse many more victims than those who abuse girls. The abusers were mostly single; colleagues thought they were gay. While Roman Catholic, Anglican priests and Christian Brothers used their authority to abuse children in state care and were often sadistic and violent, the Protestants tended to have less power than Roman Catholics and were more likely to have to resort to the grooming methods commonly associated with paedophilia.

Paedophile priests and church leaders typically befriended the parents of selected victims, choosing those most dedicated to their church. This improved their access to boys and greatly reduced the risk that parents would report them to police if their behaviour was discovered. They visited the families, stayed for dinner and found ways to involve prospective victims in activities outside their homes. Adelaide Anglicare worker Robert Brandenberg attended the author’s local church and ran the Church of England Boys’ Society (CEBS) for 37 years. The Society accommodated a tri-state paedophile network. The published history of CEBS in Tasmania includes the names of at least four men who were subsequently charged with child sexual abuse. Tasmania’s former Archdeacon Louis Daniels pleaded guilty to thirteen counts of sex offences against young boys between 1973 and 1993. Abuse survivor Steve Fisher said that priests would go to each other’s houses taking boys with them to be sexually assaulted. Victimised by the Rev. Garth Hawkins, Fisher alleged there was an organised paedophile ring in Tasmania involving doctors and MPs as well as clergy.

In 2003, the author was invited to provide seminars for clergy and parishioners in the Hobart Diocese. The request was made because, uninformed about the nature of sex offences and the grooming methods used, clergy and the church community found it difficult to believe that their beloved and highly respected Archdeacon led a double life.

Robert Brandenberg also gained everyone’s trust. He asked parents’ permission to take groups to football matches. Some parents were suspicious about a single man spending all his time with boys instead of adults and when their sons returned home, uneasy parents asked, ‘Is everything alright (or OK)?” They later learned that young people don’t associate ‘alright’ and ‘OK’ with sex. Assured that everything was alright, they gradually relaxed and when Brandenberg sought permission to take boys to a camp in the country, parents agreed, assuming (wrongly) that there was ‘safety in numbers’. Sadly it is as easy to abuse a group of boys as it is to abuse an individual .

Brandenberg made his home attractive to young people with poker and pinball machines, alcohol, pornography and popular music by the Clash, the Buzzcocks and Sex Pistols. He took kids to Chinese restaurants and let them drive his Datsun (illegally). He also had a spa pool that he used to persuade new victims to undress. A victim described him as being ‘really good if you did what he wanted but he would dump you if you didn’t’. Brandenberg routinely gave boys marijuana and alcohol before abusing them at home, in his Anglicare office and at three camps in South Australia and interstate. He displayed photographs of an estimated 200 victims on a 3m by 1m notice board in his home.

“It was a trophy room, there were about 200 photographs of boys,” a victim said. “He used to brag about how many boys he had done it to and then dumped.”

Brandenberg suicided (1999) after being charged with offences against 26 boys,) It was later estimated that he had abused and raped more than 200 boys aged from 7–15 years.

In 2003 the rector of the parish, the Reverend Donald Owers and the brother of a victim, the Reverend Andrew King were concerned that the authorities had known about Brandenberg’s crimes for several years and chose to ignore them and his victims. They called for an independent inquiry to investigate the response of the Church, saying they had raised concerns for the past four years, only to be ignored. Finally, the synod decided to establish a two-person board of inquiry to deal with the claims . One outcome of the public call for an inquiry was that the South Australian Police set up a task force to investigate 65 complaints involving 17 different child sex offenders connected with the Anglican church.

In the meantime, it was alleged that, despite mandatory reporting legislation, an accused chaplain at Adelaide’s prestigious St. Peter’s College, the Rev. Mountford, had been given the opportunity to leave the country before police were informed of reports of sexual crimes involving students.

In 2003, Governor-General Peter Hollingworth submitted to pressures to resign one month after the publication of the report by O’Callaghan and Briggs on the handling of child sex abuse by his diocese when he was Archbishop of Brisbane. It was widely thought that Hollingworth ‘shot himself in the foot’ in media interviews where he was perceived as blaming victims. A year later, Adelaide’s Archbishop George also took early retirement following pressure to resign.

So why did sex offenders get away with their crimes?

First, according to Doyle et al (2006) Catholic church was only interested in the preservation of the institution and its assets. They saw the wave of bankruptcy as a means of concealing assets and the colossal sums spent on defending criminal clergy. Legislation dating back to 1517, provides an interesting definition of the roles of priests presented in the following order:

- preserving the image of the church

- protecting the finances of the church

- protecting the property of the church

- to hear confessions, distribute communion, administer last rites and instruct the flock

- to ‘function as an agent of the bishop, transmitting and receiving information concerning the desired diocesan order”

The diocese ‘had no need for laity interference’ (Doyle et al p280)

Second, too many bishops and clergy were seen to have violated the celibacy rule and through their violations, they relinquished moral credibility in every aspect of sexuality. Evidence also shows that clerical candidates were often subjected to homosexual sex in seminaries – both Catholic and Anglican. Corruption does not stem from the bottom up; it rains down from the top (Doyle et al, p278). However it is not celibacy that causes paedophilia; rather it is that paedophiles are unaffected by the ban on marriage and are attracted to positions that give them power over people and children in particular. Third, the grooming process targets devout families. Parents who felt honoured that their children had been chosen for special attention unwittingly facilitated the abuse by permitting overnight stays and encouraging their children to take on a role beyond that of the alter boy.

Fourth, when the cleric introduces sex, victims typically freeze and are paralysed or stunned into cooperation and disbelief. Moral and spiritual confusion are inevitable when a child has been reared in an environment that teaches that any form of sexual expression outside marriage, (especially homosexuality), is a sin. And yet here we have the priest – God’s representative and the personification of strict sexual morality – demanding sinful sexual acts. Confusion, guilt and shame are especially toxic if victims’ bodies respond to sexual touch… as most do. An additional dilemma is that the sinner is expected to confess to the priest who, being supposedly the very source of relief from sin is also the cause of it.

Fifth: Many victims felt powerless as they became trapped in ongoing abuse that often lasted for years. They could not report it because they thought (often rightly) that they wouldn’t be believed or, when in orphanages, there was no one to report it to. Those who tried to make reports were disbelieved, returned to the monks and beaten. They had to accept abuse as normal because they had to live with it. Unfortunately acceptance is linked to victims becoming victimizers.

Sixth: Apart from fear and shame, victims had to deal with the church hierarchy. Those who made reports to bishops were often treated as the victimizers and sinners. In other religious organizations (eg Jehovah’s Witness), some victims were made to forgive their abusers in public but the latter did not have to apologise to them.

Seventh: Some abuse, such as that experienced in some Christian Brother Orphanages, met the definitions of terrorism and torture. Victims were terrified into submission.

Eighth: There were often strong traumatic emotional ties based on an imbalance of power. The victim suffered intimidation, threats and violence combined with awe and fear.

Finally, when abusers were church organists, choirmasters and teachers, they provided something that victims needed such as a mastery of music, a place in a coveted team or they professed to love their victims.

In Anglican church schools there appears to have been a great deal of ignorance relating to the habitual nature of abuse and its damaging effects. Church responses were typically directed by insurers’ lawyers who instructed bishops and archbishops not to apologise to victims. Happily, the current Anglican Primate chose to ignore this tradition that caused so much distress and anger.

When child sex abuse occurred in religious schools, it was invariably facilitated by unsafe practices. The schools lacked child protection policies and child protection/personal safety curriculum that has been available in some state schools since 1985. Uninformed staff and principals seem to have been ignorant of grooming methods and the harmful effects of abuse on victims’ lives. Perpetrators gained their trust so that they missed or ignored the cues. The counsellor who abused hundreds of boys over many years was not monitored. With 50 minute lessons, he was able to remove students for hours at a time because teachers did not talk to each other and check absences. He was able to lock his room. When victims exhibited angry behaviours and were suspended he was able to provide counselling in his home where he lived alone and, of course the abuse continued. Being a counsellor he saw the most vulnerable children. He indicated to staff and victims that he was a friend of the headmaster and that gave him power. Teachers didn’t report their suspicions. When he suicided after being charged, the school held a memorial service that angered victims because it lauded him and ignored the circumstances of his death.

Ignorant head teachers often give evidence in court that the accused was the most enthusiastic and popular teacher the school ever had. They then describe the typical paedophile/pederast. He provided a range of out of school activities that gave him unsupervised contact with students at camps, drama and choir rehearsals and weekend sport. He related to the children at their own level. Kids vied to go on his camps; of course they did, he provided alcohol, dirty-talk, cigarettes and porn. When offenders present the image of being dedicated to the community, colleagues and parents support them even when they have been apprehended.

At a world conference in 2007 the author chaired the presentation of American research findings showing that child sexual abuse by clergy causes more long-term psychological harm than intrafamilial or stranger abuse because of the spiritual dimension and the fact that when they disclosed abuse to trusted people, they were not believed or supported. In a survey of 342 male victims 34% said that the person to whom they turned for help ignored them and only 7% experienced any action to protect them from religious offenders.

Are we there yet?

Have the churches learned their lesson from the massive compensation payments they have had to pay – the buildings they had to sell and the schools they had to close? Abuse survivors are under the impression that church authorities ‘still don’t get it’. There is evidence to suggest that complacency quickly returned. Last year when the author was invited to present child protection seminars for schools that paid out vast sums in compensation, staff didn’t think they needed to attend because ‘it happened a long time ago and he’s dead (or moved on)’. Some of the offender’s peers didn’t believe he was guilty anyway so child protection wasn’t perceived as relevant. Although child protection protocols had been introduced, child protection curriculum for children had not.

Since 2004, dioceses have been adopting policies for the reintegration of convicted sex offenders. The rationale is that they cannot prevent people from attending church other than by obtaining restraining orders via the courts and someone banned from one church could join another. A convicted priest who sought the retention of Holy Orders, had received no treatment in prison and continued to blame the victim but was welcomed into a church choir that included children and, from the responses on the Internet, he quickly groomed the congregation. Other parolees suggested that he had not been rehabilitated because treatment helps offenders to avoid places of temptation, not return to them.

Churches are wonderful places for paedophiles because they attract good-hearted people who believe in forgiveness and give others the benefit of the doubt. Offenders can say sorry on Sunday and re-offend on Monday confident that God will forgive them again next week. We know that offenders are highly skilled manipulators who will groom whole congregations. Some church leaders don’t seem to realise that paedophilia is not akin to a traffic offence or even robbing a bank; convicted paedophiles and pederasts may have paid their debt to society according to law but that doesn’t mean that they won’t re-offend. There is no evidence to show that religion cures paedophilia – to the contrary – and the church’s eagerness to follow the teaching of Jesus and forgive offenders could prove to be yet another costly exercise, placing it and children at further risk.

It seems that we have a long way to go before those responsible for church communities have a sound understanding of child sex offending. Quite clearly, there needs to be an educational programme of substance for church leaders of all denominations as well as for new recruits in theological colleges. All schools need child protection curriculum for children from pre-school through to secondary as has been available in New Zealand and, to a lesser extent, in state schools in New South Wales since 1985 and now in South Australia. All teachers need to be trained to recognise abuse and the grooming methods used by abusers. Community education would also be helpful.

On June 17th, 2008 the Premier of South Australia and heads of all the churches apologised to victims of abuse that happened while in their care. The Premier said that ‘sorry’ is not enough. There has to be action too. The families of victims made it clear that they are a forgotten constituency and there needs to be church-sponsored research into their needs. In terms of possible re-connection with their faith and the possibility of finding healing in that re-connection, there needs to be research into what abuse victims, family members and other ‘church damaged’ people would find helpful.

Four years ago, church leaders saw the need for research into the methods used by convicted clergy and church personnel in both Anglican and Roman Catholic churches to seduce children and their families. They needed to know what power structures helped to perpetuate abuse and how the church could re-organise itself in order to prevent a re-occurrence in the future. Has that research been done? If not, why not?

No doubt some think that churches have moved on… that there is an awareness of the prevalence and destructiveness of abuse and that protocols are in place to make children safer. The churches can’t take credit for that. In Queensland it was the persistence and courage of journalist Amanda Gearing, Bravehearts’ Hetty Johnston and survivors such as Beth Heinrich, who, often at great personal cost, led to the Inquiry into the church’s handling of abuse. In SA it was the Rev. Don Owers and (now deceased) the Rev. Andrew King, survivors and the media who forced the church to live up to its values.

Recent changes and new measures must not be seen as an end in themselves but as an intermediate stage in an organisational process. The next stage must be to ensure that espoused aims in responding to victims are adopted in church culture. Owers points out that there is little evidence of the Anglican church being willing to engage realistically with survivors, their families or advocates. Despite the apology, the Healing Steps protocol was launched in Adelaide without any consultation with survivors . Despite protests there was no attempt to create structures that would allow stakeholders to have any input into relevant church policy. Owers found that, at best survivors were only asked to comment on documents already written. And were survivors involved in the production of the draft on the reintegration of convicted sex offenders into their parishes.

Sadly, from the victim’s perspective the church response is characterised by controlling, paternalistic attitudes that assume the right to impose solutions, thus continuing the pattern of disempowerment that contributed to their victimisation in the first place. This creates barriers to healing and deprives the church of unique opportunities for learning. Genuine and committed dialogue between survivors and church leaders would offer the promise of new knowledge, better prevention and capacities for healing. Church leaders could then hold up their heads and truthfully say that they have taken the complaints seriously.

About the author

Emeritus Professor Freda Briggs AO is a researcher and lecturer in child development at the University of South Australia, Magill Campus. In 2003 she was co-inquirer into the handing of sex abuse cases by the Diocese of Brisbane. She is the author of 17 books relating to child protection and has researched in Australia with child sex offenders, victims, their families and professionals reporting abuse. Her awards include:

- Order of Australia, 2005

- Rotary International Service Award, 2005

- Queen’s Centenary Medal, 2003

- Senior Australian of the Year, 2000–01

- inaugural Australian Humanitarian Award, 1998

- ANZAC Scholarship for research of value to Australia and New Zealand, 1997