by Sconey (guest author) on 20 January, 2010

It was one of those days when I didn’t want to talk to people. I just wanted to be left alone. It was a grey cold day in the city of churches. I walked down Hindley Street. The place has changed. It has been many years since I said I would never come here again. All my old squats are gone. New shops are everywhere; all the old hang outs are long gone, just their shells remain with different faces. But the memories are so strong. It feels like the street is still a part off my blood. The doorways I used to sleep in, the smells and aromas set off flashbacks and instincts in my brain. I felt like a homing pigeon coming home. I had a lot of good times living here as a kid and many bad times. I was a ward of the State, on the run most of the time and in those days I was not the only kid hanging out there. Many kids were there. All surviving in one street, living any way they could. We were there through family and systems abuse.

We all had our tricks to getting money to survive. Begging was one of them. A pie or pasty was under a dollar then. Some nights the street had kids on every corner begging for food, cigarettes, drugs or money. Many kids sold their souls there as well. The street was a meat market for the predators and pimps.

The things we did to survive! We were so young. We did not know how we were being abused by those who so cunningly took advantage of our situation. We could not even fathom how it would leave scars so deep in us; that the nightmares and memories would last a life time. This street had all of the seven deadly sins in it. It took many lives in many ways.

Strolling past the big M on corner of Hindley and Bank Streets, I turned towards the railway station and an old friend walked past. This blew me away. He was still walking the street after thirty plus years and going through bins. He was hanging out in town many years before my time in the street. This just saddened me even more. I walked up to him and called his name. I was one of only a few that this person ever spoke to. No one ever knew his name except me. He turned and looked shocked that someone recognized him. He realized who I was after a good long stare at me. The feelings were racing through my mind. I quickly opened my wallet and said to him, ‘My friend, the system is still failing you. You can have what ever is in my wallet’. I had two fifty dollar notes. He took both of them. Immediately after that my eyes hit the ground. I was in tears and I couldn’t even look him in the face as I did not want him to see my tears running down my face. I mumbled, ‘Take care of yourself, my friend’, and turned towards the railway station.

The day rapidly went from grey to very dark after that. I walked over the River Torrens bridge on King William Road and looked at the toilet block in Jolley’s Lane. Many kids hung around there in the old days, trying find places to sleep late at night. This was a dangerous place to sleep. You were often woken by men playing with themselves, enticing you with money to come with them to their houses and with cold frozen backs most of us went with them.

Well, with all those old memories I really needed something I gave away a long time ago – alcohol. So I quickly found the nearest pub with an auto teller machine and started drinking heavily. I found the need to gamble and sat at a poker machine and a started playing. However, losing was more like it.

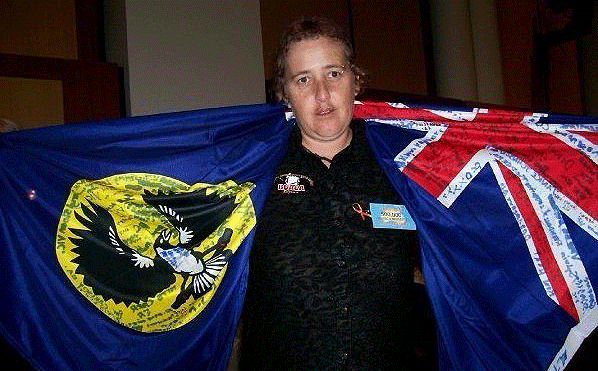

Sitting besides me were three old fellows yakking away. I have big ears and don’t mind old fellow stories, so I listened to what they were saying. The subject was the Mullighan Inquiry and the wards of the State. They were also talking about things that happened to them in the past. Their stories were not too bad. They had homes and families in their day, whereas we did not. Some of their comments were along the lines of, ‘They expect us tax payers to pay for those rotten criminal kids; I would have snotted my kids if they were like that; They’re still alive today so they must have been treated all right; The joke of it!’ This subject went for another ten minutes with them knocking us wards. The last comment was, ‘I reckon they are all liars!’

After this I was boiling. I had to say something to these silly old fools and I had to keep my cool in my intoxicated state. Still I stood up proudly and said, ‘I am one of the Forgotten Australians you are talking about. You think because of what happened to you, we do not deserve retribution or compensation some how. Well let me tell you something fellows? Your generation denied what was happening to us; you closed your eyes and let it happen and you say you are not to blame as well. You are idiots and you should be ashamed. Until you have walked in our shoes and walked down our paths, you know little about us and our lives. You are here in the pub spending your government pension, with obviously not a worry in the world, knocking the disadvantaged and underprivileged’, I went on to tell them, ‘It was in papers many times back then and in your face, when you could have done something about it. But what did most of the public do? They closed their eyes and looked the other way or abused us. Yes old fellows, you are to blame too, along with the Government’.

That shut them up.