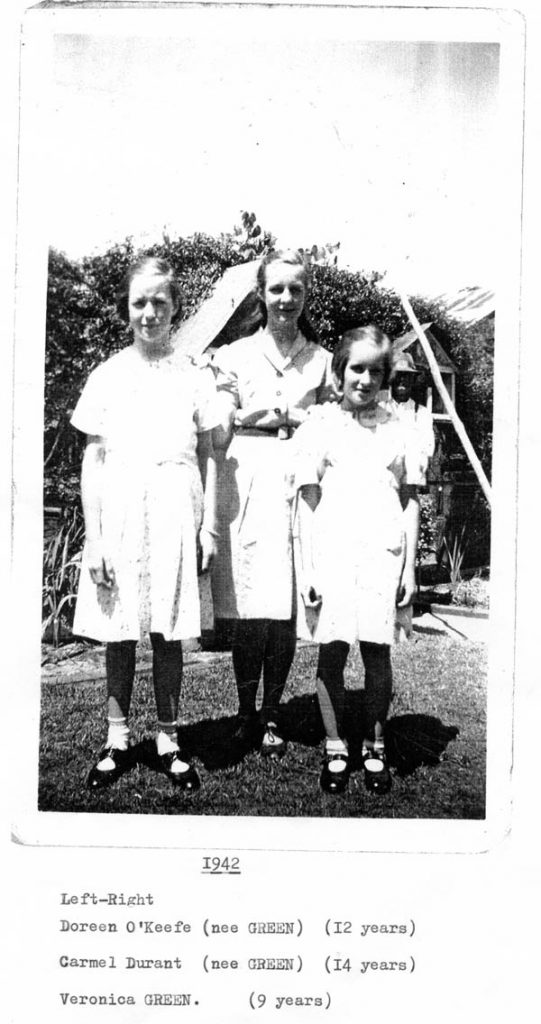

by Carmel Durant (guest author) on 5 March, 2010

LOST CHILDHOOD

The Great Depression of the late 1920s–1930s not only deprived hundreds out of work but also redundancy. This had a flow on effect of poverty and sickness.

Both our parents were very sick, due to poverty and malnutrition. To help out families with children, soup kitchens were established at the schools.

Indelibly etched in my memory was seeing my Mother very sick in hospital. Within a few days of this visit, my two sisters and myself and a very small suitcase were put on a train with woman we did not know, nor did we know where we were going, and that would be the last we would ever see of our home for life. We were now ‘STATE WARDS’. I was eleven years old.

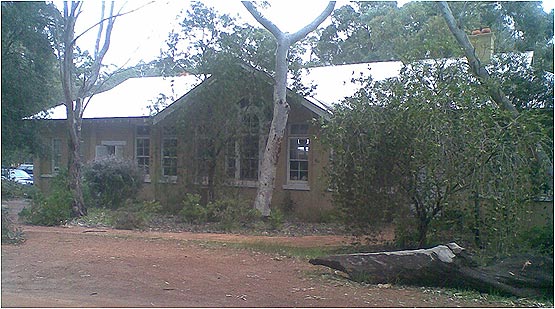

We arrived at ‘Bidura’Home in Glebe. It was all so different, as we had never been to the City or away from our country town. On arrival our small suitcase was taken, were issued with blue uniforms and black stockings. We were chastised for not saying ‘thank you’ to the person in charge when we received our outfits. Most embarrassing, was having to strip in front of at least six complete strangers … walk up three steps to the bath and, as a matter of routine, having your head ‘treated’, no matter what your age.

Within a week or so we were taken to Camperdown Hospital to have our Tonsils and Adenoids removed.

Chores were allocated in the Home. My job was to make numerous beds in the dormitory, sweep and scrub the floor, then asked the supervisor to inspect it and if passed then you could go to ‘SCHOOL’. This was one room in the grounds with no qualified teacher. We did craft, mainly puppets.

Saturday came and we would be fitted out from the ‘clothes cupboard’, containing frocks, shoes etc. What looked OK, is what you wore to Church on Sunday. Another child would have that outfit next Sunday. We were marched in line to the church, then back to the Home and back in uniform.

We hadn’t been in the Home very long when our Dad came, and talking us onto the Black and White tiled verandah, at the front of the Home, he told us our Mum had died. She was only thirty six. There was no support or gentleness from those in charge!

Came the day and down to the ‘store room’ we went to be fitted out with a new set of clothing and off to our ‘Guardian’ [or ‘foster mother’]. She was a lady with her grown son, at Waverley. Her husband was a train driver up Newcastle way.

We three shared a double bed and on Saturdays we would spend the day burning the bed bugs with a lighted candle. We did not sit at the dining table; we sat at a small table in the laundry. The drink that we had was made from discarded tea leaves with hot water poured over them.

I remember the cases of tomatoes kept under the bed. They were kept so long they were unfit for consumption, but they were good enough as far as our Guardian was concerned to be put in our sandwiches for school. The Nuns, at Holy Cross, noticed that we were not eating lunch and throwing the sandwiches in the garbage. They gave me money to buy either a pie or a sandwich, which I broke in three and shared with my sister, so that we all had a small amount to sustain us. The episode was reported to the then called Child Welfare, with the result that we were returned to ‘Bidura’.

My next job at the Home was to help in the kitchen. I spread bread with Golden syrup (no butter) for the children coming back from ‘School’, help prepare meals, help feed the small children, help prepare the food and to do the washing up.

It was time to go back to the ‘store room’ for a new set of clothing. This time we were headed off to Mittagong. Our ‘Guardian’ this time, in my opinion, was a very caring person. We all worked together in our little garden. She took us up to see our Dad, who was in Randwick Hospital. We could only see him from a distance as he had a contagious disease. She let us be children. However, this was short-lived. I came home from school one afternoon to find her lying on the bedroom floor, she had had a Stroke and later passed away.

Back to ‘Bidura’ … we knew the routine by now. My allocated work at this time was, wake up at 5.30 am and wake the staff with their morning tea. 6am, set the table in their dining room, bring their meals, clear the tables, clear the dining room and wash their dishes. Then there was the Black and White tiled verandah out in front to be scrubbed. This was the daily routine, then go to the ‘School’.

Back to the ‘store room’ for another outfit, this time we were off to Mascot.

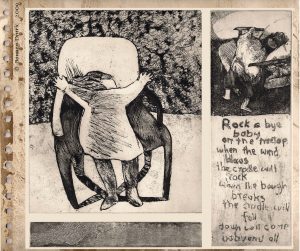

We were not allowed to go inside the house only for meals and to sleep. We spent the majority of our time in a little tin shed in the backyard that had a piece of hessian covering the entrance. We were there even when it was raining. We occupied ourselves by making small craft. My youngest sister had been given a small toy which she loved, she dressed it. One afternoon after arriving back from school we were devastated to find the toy and the little bits of craft had been burnt or thrown away. You daren’t ask ‘why?’.

Saturdays were spent cutting the lawn down on our hands and knees, as all we had to cut it with was a pair of hand shears and scissors. Also down on our knees we swept the kitchen floor with a dust pan and brush, and then we had to scrub it. We also had to make sure there was enough coal inside for a fire.

Our Dad, who was ill in Randwick, sent us lollies from time to time. These would be rationed out to us; also the letters he wrote would be opened and censored. Then came the day when the ‘Guardian’ told us there would be no more sweets or letters as our Father had died … There were no hugs or soothing words.

On my sister’s tenth birthday we were sent out to the Cemetery, out Malabar way, to place on our ‘Guardian’s’ husband’s grave. He had passed away three weeks after we arrived. While we were there the wild yellow flowers were out, so we picked some and went around putting them on other graves. What child has ever spent a birthday like that?

During all these years we were not encouraged to have friends around or go to anyone else’s place. No one to play with nor did have any celebrations such as birthdays or Christmas. We were at ‘Bidura’ for one Christmas and we were given two boiled lollies … no toys or anything we could cherish.

Our younger brother was placed in a different Home; he was only five years old. Then he was placed in a Remand Home (only five) … he had not done anything wrong. He was then place in the care of a very wealthy family in Bellevue Hill. We did not see him for some years. At this family home (who entertained a lot) he was expected to carry chairs and down flights of stairs. He had contracted TB of the ankle and had one leg in a caliper, so this was difficult for him. Our Grandmother who came down from the country to see him was horrified and eventually gained ‘Guardianship’ of him and took him back to our country town. He was now seven years old.

For me, all this Trauma came to an end the day I turned eighteen, but my two sisters remained on for a while. My second sister went back to ‘Bidura’ and my youngest sister entered the Convent.

Through our adversities, we all achieved our ambitions. My second sister and I became Trained Nurses and our youngest sister became a Teacher, also helping out the homeless and a mentor to many. Myself, I became an In-charge Nurse of the Operating Theatres and Emergency Department for many years. Our youngest brother became a Motor Mechanic.

Our Parents would have been proud of what we achieved.

I am now Eighty-Two years old and these memories remain very clear. What happened to our Childhood?

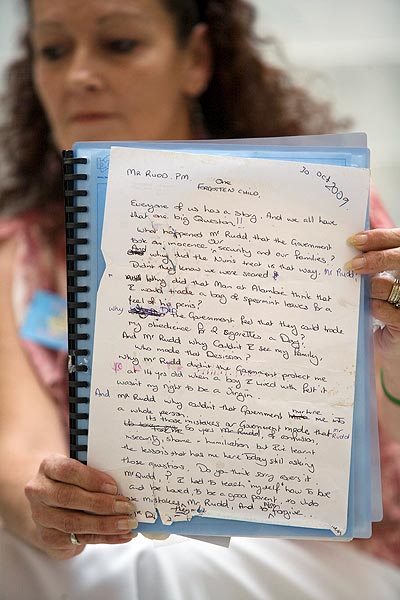

My young brother was fortunate enough to go to the Apology given by the Prime Minister Mr Kevin Rudd.

These are not just stories, they are FACT and now all of these events will be believed!

Written by Carmel Durant (nee Green) January 2010