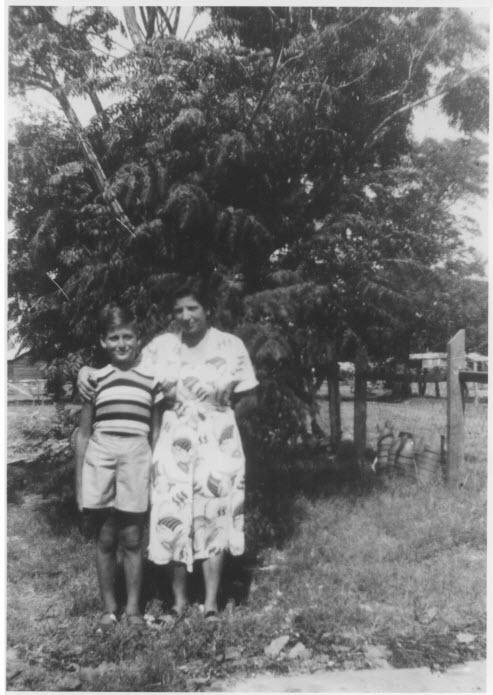

Carole May Smith shares a poem written by her deceased brother Christopher Peter Carroll. Chris grew up in homes in three states. He died just before Carole was to meet him after a 15 year separation.

Chris grew up in Largs Bay Cottage Home, SA; St Michael’s Home, Baulkham Hills, NSW; Bridgewater Care and Assessment Centre, WA; and, Hollywood Children’s Village, Hollywood WA.

Carole writes:

My brother wrote this poem in 2001 not long after the Salvation Army found him for me after some 15 yrs at least apart.

He wrote these words while in rehab in a bout of depression trying to deal with the horrors and terrors inflicted on him, me and our other brother and sister in our childhoods.

Bro passed away in Feb 2004 of a massive heart attack before we had the chance to meet again in person.

These are his story through his own words …

The Crucifed

What are they that we bear them in mind?

Welcome us no!

They pay us no mind.

Here is a question to ponder aloof _

Is Man kind?

Harken to me quickly truth,

for it has nought to do with mankind.

Tales of woe and rusty knights,

To fearful dreams and sleepless nights.

Of things etheral and in silhouette,

Only ethetics,

vain,

slimy

silly and wet.

What will befall me this awful morn?

When will they gather?

and who for me will mourn?

Surely keep my mind and heart

rock steady and able,

So to keep me from murder intent,

of the likes of Cain and Abel.

For fiery arrows at me they have threw,

Forgiven me not,

they pierce me through.

Truly this morning is both dire and grave,

They have conspired together,

and have already dug my grave.

What have I done for this to earn?

If they only knew –

Behold!

When will it end?

For they now have bound me

in this dark dank hold.

This time I was broken,

busted

and kneed,

They never once showed pity,

or tended to my earnest need.

Kicking and bashing me

they thought it light,

Keeping me imprisoned,

they are blinded

and cannot see the Light.

The assaults and insults,

my body torn,

it bears the score,

They slashed and hacked,

laughing and mocking

as they added their score.

Hear the screech of the baleful crow,

How they mocked me,

and stupendously did crow.

It was terrible indeed to pay this fare,

Ignoble and ignorant

they despised

what was honest and fair.

Dear sweet mankind,

who cut and vexed me to the vein,

Dead ears to listen,

all given freely and truly not in vain.

Splintered and shattered

they pummel me to an un-Godly site,

Satanic untold horrors are my plight,

as I now fight what defies sane sight.

Please forgive them Father

and be not cross,

Pagan rituals they rather,

as they hammer me to a cross.

Father keep me true

and in fair stead,

For they dishonour me,

and defy logic instead.

Likened as a dog,

they hung me from a tree

at a place called the skull,

Loathesome men,

their crime is clear,

while cavorting

and drinking wine did scull.

So now here I am,

I beseech Thee

with my voice

and arms out-stretch,

So be it,

I can do no more,

for I have done my stretch.

I go now to a glory

where everything is majestic

and bright,

I truly forgive them,

for they are slow witted,

dull

and not quite bright.

Dreadful men what have you done?

I will surely mark your crowns.

desire me,

and wake up to be ready

in time to receive

the promised golden crowns.

Come be with ME

and I will let you ascent,

Can you understand ME

or the energy I’ve spent,

all I ask is an oath of accent.

All things must be

and will be

to MY true accord,

Any who defy ME,

I will accordingly sever the cord.

I AM who I AM,

and there is nothing

that I do not know,

If you ask ME properly

and truthfully

I would never say no.

I was and AM

even before time began to flow,

I will let you drink from the waters

that will never cease to flow.

by Christopher 2001