by Gabbi Rose (guest author) on 10 November, 2011

Gabrielle Rose shares photographs from the reunion of former inmates of the Winlaton Youth Training Centre, held at Open Place, Melbourne, on 29 October, 2011. Continue reading “Reunited”

by Gabbi Rose (guest author) on 10 November, 2011

Gabrielle Rose shares photographs from the reunion of former inmates of the Winlaton Youth Training Centre, held at Open Place, Melbourne, on 29 October, 2011. Continue reading “Reunited”

by Christine Harms (guest author) on 3 November, 2011

Christine Harms is performing at the National Museum of Australia as part of Music to Remember, 16 November, 2011. This concert starts at 11am and has been scheduled to acknowledge the second anniversary of the National Apology to Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants.

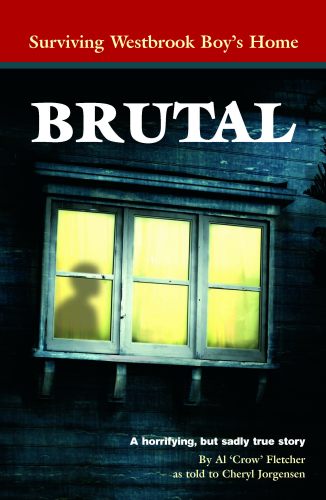

Hear her latest recording of her original song Give it Up, dedicated to Al ‘Crow’ Fletcher, the author of Brutal: Surviving Westbrook Boys Home by Al Fletcher as told to Cheryl Jorgensen.

Play Christine’s recording of: Give it up

by Rachael Romero (guest author) on 2 November, 2011

View the latest film by Rachael Romero depicting, through drawings and poetry, her experiences at The Pines in South Australia. Continue reading “Magdalene Diaries”

by Wilma Robb (guest author) on 2 November, 2011

Join the Forgotten Australians’ rally in Canberra on the second anniversary of the National Apology to Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants.

When: Wednesday 16th of November 2011 at 8.30am

Where: Meet in Civic Square outside the ACT Legislative Assembly, off London Circuit, Civic

Who are Forgotten Australians? They are approximately 500,000 Indigenous, non-Indigenous and former Child Migrant adults who were incarcerated as children in church, charity and state run orphanages, reformatories, training schools, psychiatric hospitals, children’s homes and in foster care during the 20th century from the 1930s – 1990s.

Please RSVP by Friday 11 November to admin@wchm.org.au or 6290 2166.

This event is supported by the Women’s Centre for Health Matters Inc. (WCHM), Woden Community Services Inc., and Women and Prisons (WAP). For more information please contact WCHM on (02) 6290 2166.

by Adele Chynoweth on 27 October, 2011

Listen to author Al ‘Crow’ Fletcher talk about his experiences at Westbrook Farm Home for Boys.

Al joined Adele Chynoweth at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra on 1 September 2011. He is the author of Brutal: Surviving Westbrook Boys Home by Al Fletcher as told to Cheryl Jorgensen.

Hear Al Fletcher’s perspective as a survivor or read the transcript on the National Museum website.

by Ann McVeigh (guest author) on 2 August, 2011

‘My identity was stolen from me’. Child Migrant Ann McVeigh shares her personal history and photographs of St Joseph’s Orphanage, Subiaco (now Wembley), WA.

As a child migrant my identity was stolen from me the moment I left my home land, without my mother’s consent. The name that I was born with was changed when I was put into Nazareth House in Belfast. I came to Australia on the [SS] Asturias when I was 5 years old in 1950.

On arrival in Western Australia I was sent to St Vincent’s Foundling Home in Wembley till I turned ‘a big girl’ 6 years of age. When one turns 6 one is sent to St. Joseph’s Orphanage which was next to St Vincent’s. Once placed there I still had my name changed and the date of my birth was changed also. Right away we were given numbers to answer to, put onto our clothes and lockers, my number being number one. Straight away you were expected to work always rising at 6 am every day for prayers and Mass. Duties being – sweeping yards, cleaning toilets, washing and polishing floors in the dormitories, classrooms and long corridors on hands and knees. Children were put in charge of children to be cared for in nurseries, kindergarten and foundling home. Laundry had to be done for private boarding schools and hospitals as well. Huge big washing machines, dryers and mangles which were like oversized irons for sheets and the like. The work was relentless and very tiring.

A lot of the child migrants were, I feel, abused both physically and mentally simply because we didn’t get visitors and had no-one to report the abuses to. Girls were constantly being told that ‘from the gutters of Belfast you came and to the gutters of Belfast you’d return’. Schooling was always under duress, beltings if exam results weren’t good enough or if you couldn’t understand what was being taught. To my mind it was likened to a modern day Oliver Twist, with all the cruelty that went on.

When I was in grade 2 I was informed that I was a very lucky girl because I received a letter from my mother. I was called up to the front of the class whilst the letter was read out to me. I never ever forgot that letter and always wondered when I would get a visit from my mother who said she’d try and come to get me to take me back to Ireland. Every time the door bell would go you’d stop and wait with hope, expecting your name to be called. In the end it would be a joke – yeah she’s walking across water to get me – not ever realising my letters that you wrote were never passed on. My education ended in second year high when I was 15 ½ years. I was sent 300 miles up north to look after 5 children and help around the house. One day I was with 200 kids, the next day 5 children and 2 adults. The quietness was frightening as I missed my school pals terribly. That job lasted six months and the second job for only one month, another country job doing housework for a very nasty and cold family. I was never ever greeted the time of day – just given orders on what had to be done for the day. No payment ever received. The third country job was as a shop assistant which I really enjoyed, but after 11 months I was very upset when told I would have to go back to St. Joseph’s. When her son came to pick me up I locked myself in the bathroom until I was given an assurance that I wasn’t going back. I was sent to a juvenile detention centre which scared me somewhat when I woke up the first morning as there were bars on all the windows and I thought that I had been sent to jail.

Because I rebelled I was given a welfare officer to help me out with jobs and accommodation. It was she who got my mother’s address and encouraged me to put pen to paper. Because I was eighteen I had to correspond by mail till I was allowed to go overseas and visit the family when I turned 21. When I first started to write, my mother told my siblings (2 brothers and 4 sisters) that I was their cousin from Australia. As they were still very young and still at school, not much explanation was needed. In 1967 I met my family for the first time. Being shy, I was very nervous, wondering if I was going to be accepted, but I needn’t have worried as everything turned out well.

When my mother passed away, I took my one year old son with me to the funeral. Sadly, she was buried on my birthday. When my son was eleven, I took him over again so he could meet all his cousins. It was wonderful to see them all together, it was like he belonged and was wonderful to see.

In 1988 I bumped into a school pal and she was telling me that when she received her personal papers from the welfare department, she had a breakdown. You see, because of her Afghan heritage she was dark skinned and in her papers said, although she was a very pretty little girl, she was unsuitable for adoption. We got talking and wondered how the other girls had faired when they got files. She told the doctors that …. the treatment the girls got at the home would come out – so he went to the Wish Foundation and formed an organisation called ICAS (Institutional Child Abuse Society). We went to print and on air and received a lot of support, especially after the radio interview. We got a lot of calls from the boys who were in Clontarf, Bindoon, Tardun and Castledare, telling us about the abuse that took place. We only heard from one or two other girls that they weren’t interested and just wanted to forget. After all this happened the boys formed their own organisations and the world got to hear of the terrible treatment the migrants and Aussie kids received in the institutions of the day.

I was on the committee that erected the child migrant statue in Fremantle, outside the Maritime Museum. My partner is a child migrant also and both our names are on the Welcome Wall, very close to the migrant statue. While on the committee, submissions were invited for the Child Migrant Memorial Statue, although my poem wasn’t accepted, these are my thoughts on the very sad history of child migration.

They did not know what lay in store

holidays abroad to far distant shores.

Yet in their memories as often recalled,

brothers – sisters

and friends what’s more.

Where are the families

that they once had

Back in their homelands,

How very very sad

Thousands of children crossing the line

Holidays and memories lasting a lifetime

Ann McVeigh 29 January 2011

by Darren Sugars (guest author) on 19 July, 2011

Darren Sugars sings ‘Sleep Well Tonight’, an original track which he says is ‘inspired by the personal narratives of two brave Forgotten Australians who are dear to him’.

Thanks to CLAN for providing the National Museum with a recording of the song.

by Wilma Robb (guest author) on 7 July, 2011

The Australian Senate recently voted against Senator Nick Xenophon’s motion that the Heiner Affair be referred to the Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee for inquiry and report. Listen to Bravehearts‘ founder Hetty Johnston’s response.

Download the Hetty Johnston interview with Michael Smith on the 2UE website.

Download the Hansard excerpt (PDF 263kb) to read the report of the Legal and Constitutional References Committee discussion and to see how senators voted on 23 June 2011.

by Gabrielle Short (guest author) on 27 May, 2011

Gabrielle Short has organised a reunion of former inmates from the Winlaton Youth Training Centre. The reunion will take place at Open Place in Melbourne on 29 October 2011.

Gabbi has announced:

We are holding a reunion for all those who spent time in Winlaton Youth Training Centre October 29th 2011. I think this will be a great opportunity to catch up with old friends and take a trip down memory lane. I’m sure there will be plenty of interesting stories to tell good & bad. Most of us were put there for no fault of our own, most of us were only running away from the system itself that failed to care for us in other homes, some because of being exposed to moral danger, some as a result of rape, pregnancy, poverty, the list goes on. We were not the bad girls that we were lead to believe and portrayed to the public. I know a lot of girls who still to this day will talk of other homes they were in but not Winlaton because of the shame and stigma that was once attached with being in Winlaton well it’s time to hold our heads up high and be proud of who we are and the fact that we have survived and are still here to tell our stories.

by Wayne Chamley and Tony Danis (guest author) on 23 May, 2011

Dr Wayne Chamley, an advocate from Broken Rites, shares the history of Tony Danis. Tony was held in the Mont Park Asylum after escaping from a home run by the brothers of St. John of God. Wayne did a lot of advocacy work for Tony and he now lives comfortably.

Wayne writes:

When I first found Tony, he was living in a horse stable, working 6 days a week, as a stable hand and being paid $300 for the week’s work! Tony has poor literacy skills because he has never received any education. He is actually quite smart and because of his life-journey, he is now very street wise.

This is the statement that he dictated to me and which he sent as a submission to the Forgotten Australians Senate inquiry. It is a very sad and disturbing recounting of his appalling treatment. You will see that he identifies a Br. F. as one of his abusers and then this same person has counter-signed his committal certificate, as was required under the Lunacy Act.

Tony Danis’ experience at a Home, in Victoria, run by the brothers of St. John of God:

I was born in 1946. I live alone. Since about the age of 16 years I have been able to work sometimes, in either full time or part-time work to support myself. I have worked in a range of manual jobs. At other times I have had to live on social security while experiencing serious depression. For most of my life I have suffered seriously from asthma and this has been getting progressively worse in recent over the last six years or so. At the beginning of this year I had to finish working because of this illness and ongoing depression.

Records that I have obtained about my childhood indicate that I was first placed into care in St Anthony’s and St Joseph Boys Home at the same time. We were later moved to a Home for Boys … that was operated by the St John of God Brothers. At times I was taken for holidays to the St John of God farm … and also to a house that the Brothers had …

Placement in [VIC] Institutions

- St. Anthony’s Home: 1950 to 1951

- St Joseph’s Home: 1951 & 1952

- St John of God Home: 1952 to 1960

Domestic Routine

As I recall, the domestic routine … as fairly constant. I was in an upstairs dormitory and as I recall all of the boys who slept upstairs were the ones who either never, or rarely, had adults visit on weekends. The boys who got visitors were on the ground floor.

Every day boys were woken early, they then dressed and went to the dining room for breakfast. After meals some boys were rostered to clear the tables, sweep the floors and help with dishwashing. Boys not rostered were allowed to go outside and play. Later a bell went and boys went into classes.

While many of the boys went to classes for most of the day, I only went to short classes in the morning. After this I was put onto other duties. These varied and included gardening, maintenance jobs, working in the kitchen after lunch and helping to prepare vegetables for the evening meal, cleaning the dormitories and making beds.

After school classes had finished we were allowed to play outside and then we would come in for tea. All boys had showers either before or immediately after tea and showers were supervised by the brothers.

After dinner, boys were allowed to watch TV until about 8.30 pm at which time they had to go to bed. Before going to bed, many boys upstairs were given a red medicine every night. This made me feel very groggy.

On weekends, boys were allowed to play various games and sometimes we were taken by brothers to a football match. Sometimes the brothers would get very drunk while we were at the football.

Experience of Abuse

I experienced severe and sustained abuse which was carried out by several of the brothers when I was in the Home … and at the … Farm and in the house …

I experienced the following abuses

- Sexual abuse

- Physical abuse

- Starvation

- False imprisonment

- Incarceration in a psychiatric institution sat the instigation of the brothers

- Deprived of an education and subjected to unpaid child labour

Sexual abuse

During my nine years (approximately) in the Home … I was sexually abused many times and by several of the brothers. I also experienced instances of harsh physical abuse. The sexual abuse varied from fondling by one and sometimes more brothers and it took place when I was in the toilets and during the night when I was in the dormitory. Over a period of 3-4 years I was abused frequently by five brothers.

On another occasion I was raped … by Brother F. in a toilet. All the time I was crying and in a lot of pain.

On another occasion when I was about 10 years old, I was held down by three brothers in the corridor of the dormitory and, while one continued to hold me on the floor, the others manually pulled out some emerging pubic hair and chest hair. As they did this, they joked and referred to my having “bum fluff” which had to be removed.

The sexual activities of the religious brothers were not confined to within the precincts of…[the Home]. On occasions boys were taken from Cheltenham for holidays. In my own case I was taken for holidays to the farm and to a holiday house.

The two brothers at the holiday house were Bro. H and Bro M. Both these brothers abused me and I was also abused by a Bro. B while I was at the farm.

Physical abuse

From the time I was placed into ‘care’ … I experienced physical abuse at the hands of various brothers and I lived in fear. I was not the only boy who was treated like this although I did seem to be singled out, on several occasions, for particular punishments. The abuse took the form being punched in the body and/or hit on the side or the back of the head. On other occasions I was beaten by an individual brother using a piece of cane and at times I was whipped by a brother using a leather strap.

Many times I received a beating when I arrived late at the breakfast room along with another boy, L. who had red hair. The circumstance that led to my often being late for breakfast is linked to the fact the L. and shared the same dormitory. Each morning L. had to put calipers on his legs on order to be able to walk and if L. was slow in getting ready, I would stay in the dormitory and help him to put on his calipers. Thus I was often punished for helping my friend L. while L. himself was punished for being late because of his having a physical disability. Another boy who was often punished for being late was L. W.

Starvation

Hunger was a constant companion while I was in the ‘care’ of the brothers. This reflected the fact that the amount of food made available to boys was insufficient and often the meals lacked any variety. Consequently, sometimes boys did not eat a meal then our hunger got worse.

When boys are staying at Lilydale we were allowed to help with some of the farm work including milking cows and feeding chicken and pigs. The pig’s feed included leftovers from the kitchens and this was transported to the piggery on a truck or a trailer. I can recall occasions when I and other boys would ride on the same vehicle going to the piggery and we would eat the best of the scraps before they were fed to the pigs.

False imprisonment

On one occasion when I was about 11 years old, I was whipped very heavily by a brother using a leather strap. Because the assault upon me and the pain that I was experiencing, I could not stop crying and so I was then locked in a dark room and left there for three days. Every now and again I was checked by a brother and during those days I received only bread and water.

When I was let out of the dark room I was crying and very upset. I learned that while I had been locked up, all of the boys had been given new leather scout belts. Later that evening, Bro. T. came to see me in the dormitory. He had brought me a new scout belt and the buckle had my own name on it. Bro. T. was a very kind person. Although he knew about the abuse that was going on, because boys told him, he did nothing about it.

This experience of being locked in a small dark room has had a profound effect upon me and to this day I experience uncomfortable anxiety if I am in a dark room and the door is closed.

Incarceration in the psychiatric institution at Mont Park

At the instigation of the Brothers of St. John of God, I was incarcerated in the Mont Park Asylum for more than two years.

The circumstances that led to my being incarcerated need to be explained. When I was 12 years of age I ran away from the Home on three separate occasions. My motivation each time was to try to escape from the abuse, the terrifying experiences, the persecution and regular beatings that I was getting at the Home. The sequel to each escape was for me to be returned to [the Home] and then I was punished for my action. Usually this took the form of further beatings by various brothers.

In one escape I managed to get to the Royal Botanical gardens and I entered the back of Government House. One of the gardeners met me and I was taken to a kitchen at the back of the large house. After a short time the wife of the Governor came and talked to me. She arranged for me to be washed and given food and I told her about being whipped and abused by the brothers. Her response was that I was making the story up. Soon after, a police car arrived and I was taken to a police station close by and I was questioned about my escape. After this I was driven back to [the Home] in a police car in the company of female police.

After my third escape I was sent away from [the Home] by the brothers and I was placed into a receiving house at Mount Park Asylum. This was a terrifying experience. I was first placed in unit M10 which was like a prison. During the day I was allowed to move around within large communal rooms and I could watch TV. As I was fairly small and only a young teenager (13 years old), I was sometimes physically attacked by some of the older patients with mental illnesses. I was not allowed out of the unit unless I was accompanied by a member of staff.

During the night I was locked up in a small cell that had bars on a window and a solid door with a small, barred, glass window in it.

I spent about two years at Mont Park until one day a Dr R. had a long talk to me. I recall this doctor made an assessment of me and then told me that I should not be in such a place. I was 14 years of age.

After my meeting with this doctor, arrangements were made for me to live in a private house in Preston where one of the nurses lived. After a short time I got a job in a local clothing factory and I continued to board at the house for a few years.

Deprived of getting a basic education and subjection to unpaid child labour

As I have outlined in the section that describes the domestic routine at [the Home], I was given little opportunity to get a formal education. This was not the case for other boys who spent several hours each day in school classes. The chance to learn to read and write was denied me by the brothers and instead I was kept in a situation of unpaid child labour. For most of the time at [the Home], I was required to do domestic work for the brothers.

In his Submission to the Senate Inquiry from Broken Rites, Wayne wrote:

We are aware of at least two statements made by different, former inmates who allege that two different boys sustained injuries, as a consequence of beatings, that probably resulted in death. One of these boys was thrown down a staircase (according to the witness) soon after he arrived at the [farm]. We are also aware of at least two boys who both experienced serial, sexual abuse and who were (as juveniles) certified under the Victorian Lunacy Act (1915) and then incarcerated within the Royal Park Asylum. This was the Order’s final response to each boy’s continuing efforts to abscond from the Home; his chosen strategy for escaping from his paedophile attackers. In one of these cases the brother who filled out and signed the committal report was the ‘alpha’ paedophile!

by Wilma Robb (guest author) on 11 May, 2011

Dianne McInnes, a PhD student at Bond University, Queensland, under the supervision of Dr Paul Wilson, is studying the adult criminological consequences of the boys at the Institution for Boys, Tamworth, 1948 to 1976. Spcecifically, the research concerns effects of instutionalised routine and enforced silence of juvenile males who did not have criminal records.

Dianne is inviting anyone connected with the Institution for Boys, Tamworth to participate in an anonymous questionnaire. Further details may be found at the questionnaire website.

by Barbara Lane (guest author) on 16 April, 2011

Barbara spent time as a child in Opal House, Opal Joyce Wilding Home, Wilson Youth Hospital, Vaughan House, The Haven and at Wolston Park Hospital (Osler House) between the years 1970 and 1979. Barbara is now the co-ordinator of the support group Now Remembered Australians Inc. In her poem One Man, Barbara pays tribute to Fr. Wally Dethlefs who helped to establish The Justice for Juveniles Group, previously known as the Wilson Protest Group. Wally also set up one of the first refuges for youth in Brisbane.

One Man

When I was young and in a place

Where no one seemed to care,

One man fought on my behalf

Though others would not dare.I’d been told I had no rights

For I was “just a kid”,

But one man fought on my behalf

And showed me that I did.They took away my childhood,

My freedom and the sky,

But one man fought on my behalf

When others would not try.They locked me up in Wilson

But now I have the key

For one man fought on my behalf:

His name is Wally D.

by Rachael Romero (guest author) on 13 April, 2011

Rachael Romero, who was in The Pines (Convent of the Good Shepherd, Plympton) shares one of her poems:

Rachael explains:

This was written right after I left the Pines, Convent of the Good Shepherd. My friend Agi and I decided to feign a religious calling so we could “do rosary” in the chapel before dinner. We had our eyes on a high window that was not barred. To escape through it was a dream, but we persisted for weeks before abandoning the idea.

Escape Attempt

Furtive, stealthy in the gloom

The noise and cracks of a silent room

Every step an inch to free life

Every inch a step to new strife

Fear, regret, anticipation

Throbbing, pulsing, circulation.

“The window’s high, the glass is thick.

All I need’s a heavy brick.”

“But what of noise? – Someone will hear

They’ll keep us here another year”

“Agi come back it is too late

I hear a key at the staircase gate

Kneel down, kneel down, make out to pray

They may not even come this way

Our chance has gone, perhaps it’s best

Let’s go back, sit with the rest

I had no-where to go anyway

Trust “Sour Grapes” to cause delay”

copyright Rachel Romero

by Adele Chynoweth on 13 April, 2011

A report, published yesterday in the Sydney Morning Herald, reveals abuse in NSW juvenile detention facilities. You may access the article here by clicking on the Sydney Morning Herald website.

by Rachael Romero (guest author) on 9 April, 2011

Award-winning film maker and visual artist, Rachael Romero, writes about the image of the knife that was used in a theatre production at the Pines (Convent of the Good Shepherd).

Rachael explains:

Imagery speaks to memory. Artifacts resonate meaning. In the Pines, (Convent of the Good Shepherd) year of 1968 we used this wooden knife in a play held as a charade for Welfare (as if we were provided for culturally). Never mind that there were hardly any books available; newspapers to read, radios to hear or any news crossing the barbed wire fences of our laundry prison. We were told to offer up our suffering for the saving of souls. I see this knife as a kind of Magdalene cross we were nailed to. After-all we were stigmatized and a regular cross would have been blasphemy. The knife was also the image of choice for home-made tattoo in the Pines; crudely drawn into cuts on the the leg in Indian ink–a form of self injury to reify the agony we felt .

I photographed the second image of my feet “on the cross” eighteen months after I got out. At sixteen–this is how I felt– crucified, but not redeemed from the extra judicial incarceration I had experienced. I had no-one to tell. Everyone looked away, pretended nothing had happened.We have only just begun to break this terrible silence in “the lucky country” so that other unwanted children will cease to be so savaged.

The knife was used as a prop for the production of HMS Pinafore (image of the programme below), performed by inmates from the Pines. Rachael recalls:

It was directed by Mother Lourdes I believe. I made the drawing and did the scenery and sang in the chorus. I don’t remember much about it except that I was always glad to make art instead of working in the laundry.

The welfare workers, priest and family members were invited. It was all a big show to look as if we were being cared for.After the performance the priest requested that my blonde curls be shaved and presented to him. I refused.

by Warren Porter (guest author) on 5 April, 2011

Following on from his autobiography, A Tormented Life, Warren Porter writes the story of his deceased brother, Graham Davis. Warren writes about their abusive stepfather, how Graham was sent to Westbrook Farm Home in 1961 and police violence. Warren argues the case for a Royal Commission into the treatment of children in Australian institutions.

Warren mentions several locations in the south side of Brisbane including “the Gabber (the Five Ways)” which refers to the then layout of the railway yards in the suburb of Woolloongabba.

Download Warren’s account of his brother’s history: Graham John Davis 12.3.1946 – 23.10.1974 (PDF 7mb)

by Maree Giles (guest author) on 2 March, 2011

On 17 February, 2011, author and Forgotten Australian, Maree Giles spoke to staff at the National Museum of Australia. Maree summarises the history of the Parramatta Female Factory Precinct and her experiences at Parramatta Girls Home when she was aged 16.

Click on the link below in order to listen to the recording of Maree’s presentation:

Growing up in Parramatta Girls Home.

You can read more about Maree’s work at her website.

by Rachael Romero (guest author) on 16 February, 2011

Rachael Romero shares two of her paintings which depict experiences at the Convent of the Good Shepherd, ‘The Pines’, Plympton, South Australia.

Freddie tried to rush up the wall over the barbed wire one night. The dogs were barking on the other side. We were all wishing her up and over and out, but of course she got dragged back.

She would keep trying.

Me and Lilly did this because we felt we had become sisters in horror. Lilly had been taken from her mother to a mission then The Pines. She didn’t remember where she was from. I didn’t want to be from where I remembered.

by Al ‘Crow’ Fletcher (guest author) on 10 January, 2011

Al Fletcher’s horrifying but sadly true story as told to Cheryl Jorgensen, Brutal: Surviving Westbrook Boys Home was re-released in 2010. With a foreword by former Senator Andrew Murray, this book can be purchased from New Holland Publishers.

by Adele on 18 November, 2010

Wilma Robb nee Wilma Cassidy held up this napkin in the Great Hall of Parliament House during the National Apology to Forgotten Australians and former Child Migrants on 16 November 2009.

Wilma Robb was first admitted to Dalmar Children’s Home, New South Wales, at the age of five when her mother became ill. During her primary school years Wilma was moved within various care settings within her family, foster care and later was committed to Ormond institution for girls as ‘Uncontrollable’ and ‘Exposed to Moral danger’. At the age of 14 she ran away from Ormond and slept in a phone box in Villawood. She was gang-raped by a group of bikies. A few days later she was picked up and admitted to Parramatta Girls Home where she was diagnosed with venereal disease. She was labeled a ‘loose girl’, without investigation of the circumstances in which she acquired the disease and never talking about her rapes till in her 50s. Her ‘unsatisfactory’ behavior there led to her being sent to two periods of detention at Hay Institution for Girls.

As a teenage girl in Parramatta, Wilma, had never been charged with a criminal offence, (only a Welfare charge) was treated she believes as a de facto criminal. She was assaulted by staff (one bashing by the Superintendent resulted in her having to receive a full set of dentures at the age of 15 after her face was smashed into washbasins. Girls were internally examined to assess the ‘status’ of their virginity on arrival to Parramatta girls home and Ormond institution for girls. –. Girls who were defiant received further punishments – solitary confinement and some put on medication with the psychotropic drug Largactil.

Because of her refusal to be broken by the system, Wilma was sent, from the Parramatta Girls Home to the Hay Institution for Girls which opened in 1961-1974 as a maximum security closed institution for girls aged 13 to 18. Girls were sent to Hay despite their having committed no crime and without a legal trial. Girls were never to speak, without permission, or to establish eye contact with anyone ever. This rule was enforced despite the fact that the ‘silent system’ was outlawed in New South Wales in the late 1800s. Girls endured a regime of hard labor without school education.

The bodies of these ‘incorrigible’ girls were controlled at all times by the system. Movement was with military precision and governed by a strict regime. Girls could only speak to each other for 10 minutes a day, while maintaining 2m distance; they were forced to sleep on their right side facing the door. Twenty minuet surveillances happened all night. Girls were surveyed 24 hours a day by male staff (who were the only ones with keys to the cells) and personal experiences such as menstruation were public and exposed humiliated and deprived of privacy . Wilma said on a visit back to Hay:

It was very Cruel, inhuman and sadistic. You can still smell, feel and hear the pain in that place still today.

In later life she took up an occupation as a housekeeper to the family of Manning and Dymphna Clark. Manning Clark was the author of the general history of Australia, his six-volume A History of Australia. Manning Clark is described in The Oxford Companion to Australian History as ‘Australia’s most famous historian’. Dymphna Clark was an eminent linguist and campaigned for the rights of Aboriginal people. Wilma Robb still works as caretaker of Manning Clark House.

The napkin itself is a significant object which holds other stories. It was part of Dymphna Clark’s household items originally brought to Australia from Norway by Dymphna’s mother Anna Sophia Lodewycz circa 1910. However, enough is known of the life of the Clarks to know that visitors, significant in cultural, political and academic worlds, both national and international, were part of their social life.

At the National Apology to Forgotten Australians and former Child Migrants, Parliament House, Canberra, November 16, 2009.

Prior to the National Apology, Minister Jenny Macklin contacted Wilma asking her to submit her personal history so that it may be considered as part of Kevin Rudd’s speech. In her letter to Kevin Rudd, she explained that the Hay Institution for Girls was the equivalent of a colonial jail in its use of silent treatment. Robb was concerned that Rudd’s use of the word ‘institution’ would not cover her prison experience. Robb realized that she may not have a chance to say this on the day, so she grabbed one of Dymphna Clark’s linen table napkins, and wrote ‘WHAT ABOUT CHILDREN’S PRISONS’ in thick ink marker on each side of the napkin. When the moment came, she was nervous about holding it up.

‘I felt sick in the stomach,’ she told the National Museum of Australia.

To support her, Keith Kelly a former inmate of the equally notorious Tamworth Institution for Boys who was sitting behind her took the other side of the napkin and held it up with her. He would have equal reason to refer to the institution he had been held in as a prison. This impromptu protest sign was one of many items made by Forgotten Australians and brought to the Apology.

by Adele on 18 November, 2010

This soft toy was donated to the National Museum by Jeanette Blick.

Jeanette was a resident of Orana Methodist Home for Children, Burwood Victoria. The toy was made by prisoners at Pentridge Gaol:

A Pentridge prisoner with a propensity for, say, woodcraft or textiles might have found himself encouraged to join the ‘Pentridge Toy Makers’, a group founded in 1961 to produce toys for ‘needy’ and ‘destitute’ children. Products of the Toy Makers’ labours (upwards of 6,000 toys and hobbies annually, at their peak) were ceremonially displayed and distributed at lavish Christmas events held in the jail, to which groups of children from refugee communities, orphanages, and so on, were invited.[1]

The teddy bear was given to Jeanette circa 1962. She recalls receiving the gift:

I can remember receiving the teddy one Christmas as I did not have a family to go to for the holidays, so I had to remain in Orana over Christmas. Christmas day, I remember finding the teddy on the bottom of my bed. I did not know where it had come from as it was not wrapped and there was no tag/card on it.

I took it to the cottage mother and told her someone had left this on my bed and she said it was for me. She also told me that the prisoners in Pentridge Gaol had made the teddy.

I think I cried most of the day. This was the first gift I had received in years.

In the New Year a family came and took me for the rest of the holidays. I left the teddy on my bed as I was instructed to do (I wanted to take it with me but was not allowed) and when I came back it was gone.

I never saw it again until I opened my suitcase when I arrived in Cobram at my mother’s house. Someone must have put it in the case with the toothbrush, pyjamas and knickers that were there as well. I do not know who had done this or why.

[1] Wilson, Jacqueline Zara (2004) ‘Dark tourism and the celebrity prisoner: Front and back regions in representations of an Australian historical prison’ in Journal of Australian Studies 82: 1–13. The activities of the Pentridge Toy Makers ended in 1976 as a result of fire in their storage shed. (ibid., p. 172).

by Lynn Meyers (guest author) on 15 November, 2010

Transcript

My name is Lynette Meyers. I became a ward of the state with the Victorian government in 1959, September 1959. I was there until 1963. I was sent back to my stepfather in Queensland by the Victorian government and, on the recommendations that I have now read in my file, he was the last person I should have been sent back to. So I ran away from him immediately and went back to Victoria. From then on it was a revolving door until I got to about 30. I was in and out of Fairlea women’s prison from then right up until I was about 30 on and off over the years.

I got my tattoos on my arms when I first went into Winlaton in the lockup block in Goonyah. The girls used to have Indian ink and to rebel against the screws everybody used to tattoo themselves. I my first one was on my hand and then all over.

They used to lock us up in our quarters, that’s all, in our cells. At one stage I was in my cell for three weeks, me and another girl in the X cell. We scraped the bricks away so we could talk to each other. We had nothing in there but the floor. If you wanted to go to the toilet, you used to have to scream out for one of the screws to come and let you out to go to the toilet. They would only come when they wanted to.

What it means to me, it means that somebody is taking responsibility for the cruel things that happened to us in there. The tattoos, the drugs, the hidings, on Sparine and Largactil so we walked around like zombies. If you ever played up you got a needle in the bum by the men and just locked up, you know, solitary.

But also it means to me that I want the government not to let this happen to the young kids that are in the homes now. That is more important. What happened to me and others, we can’t do much about. But let’s not continue it on. That’s what it means.

by Wilma Robb (guest author) on 15 November, 2010

Transcript

I am Wilma Robb and I live in Canberra. I am a Forgotten Australian. I went into care when I was five years old for around about 12 months. There is no record of me leaving the orphanage in Sydney, which is Carlingford. I went home and my Mum was chronically ill, so I sort of shifted around a little bit to my grandmother, back to my mother, foster care.

I got put into an institution which was Ormond and I broke out of there because I didn’t know what was happening to me. And I got sentenced through the courts for six to nine months to the Parramatta Girls Home, and that’s where my life spiralled out of control – the systematic abuse.

The significance is that we got the apology. We are recognised – that this is still happening so I hope people – the whole system – takes notice of what did happen in the past and it’s on record. A lot of people needed this apology. Personally it means nothing to me, even though I got emotional.

My life in the orphanage, I can’t really remember it. I remember a long driveway and being alone. That was when I was five. Life in Ormond was a big wire fence around us so I was caged. When I went into Parramatta, life in there was scary and you had to survive and no, we had no real close friends. We never spoke about anything. We used to get separated if we looked like making friends. So Parramatta was really bad.

I have three children – I have four children actually. I had one baby taken off me at birth and I found him in 2006, a week after his 40th birthday, and I have three other children. They all live in Canberra. I was married and I had three children to that marriage. But all I was interested in was my three children because usually what happens is if you are abused as a child, what you will connect with is another abusive relationship. And I have just stayed away from relationships. I am stronger by myself.

by Adele on 14 September, 2010

In an essay published in 2007, convicted bank robber, prison escapee and author Bernie Matthews discusses the tragic outcomes for former child inmates of prison-run institutions – the Parramatta Training School for Girls, Hay Institution for Girls, Tamworth Institution for Boys, Hartwell House, Kiama and Westbrook Reformatory for Boys, Toowoomba.

Read ‘Reap as you sow‘ on the Griffith Review site.

by Wilma Robb (guest author) on 20 May, 2010

Former resident of Hay, Wilma Robb, shares her photographs taken at the Hay Girls reunion in 2007.

The Hay Institution for Girls was opened in 1961 as a maximum security institution for girls, aged 13 to 18, from the Parramatta Girls Home. Girls were sent to Hay despite their having committed no crime and without a legal trial. Girls were not permitted to speak, without permission, or to establish eye contact with anyone. This rule was enforced despite the fact that the “silent system” was outlawed in NSW in the late 1800s. Girls endured a regime of hard labour without school education.

Further information and historical photographs about life at Hay can be read at the website concerning Sharyn Killens’ book An Inconvenient Child.

Wilma’s painting Black, Blue and Raw was hung in an exhibition “Forgotten Australians” at NSW Parliament house from 11 April-28 April 2005. Supported and Arranged by Forgotten Australians Jools Graeme, Melody Mandena, John Murray.

Black, Blue and Raw depicts my time in Parramatta and Hay.

At Hay, I experienced a sadistic, martial discipline the (Silent Treatment outlawed in the late 1800s) designed to break the human spirit. These days we would describe it as a form of ‘programming’. At Parramatta, I experienced psychological abuse, rape, neglect and other forms of violent torture at the hands of state employees.

My torso

No-one sees what is hidden inside me. Here are the memories I have tried to suppress. Here is the sub-conscious record of life-destroying events, festering.

The little girl at the centre is me. The eyes overseeing the evil are those of one of my abusers, captured by camera from a television screen.

My baby

When I was 18, my baby was taken from me by Welfare, within minutes of his birth.

The colours

To me, yellow and purple signalled hope. At Hay, we experienced regular solitary confinement, enforced silence and regimentation. Also, they took our eyes.

The mask

At Hay, they tried to turn us into unthinking robots by brainwashing and deprivation. The Hay mask has a robotic expression and a head that has been messed with severely. My memory of Parramatta is dominated by the violence of the staff – I lost my teeth and had my face smashed. The mask has had its features flattened and is flesh softened by fists.

Wilma Robb (Cassidy) 2005