by Adele on 29 September, 2010

Father Wally Dethlefs is Project Officer for Marginalised Students at Catholic Education in Brisbane but his involvement with the homeless and marginalised began way back in 1973 when he set up one of the first refuges for youth in Brisbane.

In an excerpt from Fr Wally Dethlefs’ book: Journey into Gospel Justice: The Faith Development of a Diocesan Priest (1998) (unpublished) Wally describes his experiences as a chaplain at Wilson Youth Hospital and his establishment, with Father Pat Tynan, of Kedron Lodge.

A History of Wilson Youth Hospital

1928 – The Queensland Government bought a property called ‘Eildon Hill’ for £1400 and established the Wilson Ophthalmic School and Hostel – named after the then Minister for Public Instruction, the Honourable T. Wilson.

1930s – The Wilson Hospital was a specialised facility where eye diseases in children from country Queensland could be diagnosed and treated.

1950s – During the Second World War patient numbers at the Hospital fell drastically and it was due to the diminised numbers that the Wilson Youth Hostel began to treat orthopaedic, rheumatic and crippled children.

1961 – By this time the original purpose of the Hospital had been subsumed. In its place a remand, assessment and treatment centre for young males between the ages of eight and fourteen was established – The Wilson Youth Hospital. Initially intended to accommodate trouble-makers, emotionally disturbed children, and those who had broken the law, the Wilson was also ‘home’ to many orphans and homeless children.

1971 – A section was added to the Hospital to accommodate girls aged twelve to sixteen. Girls were often held not for committing offences but for being ‘emotionally disturbed’, ‘exposed to moral danger’ or ‘incorrigible’. In the 1973–4 financial year, for instance, only 57 per cent of Wilson girls had committed offences.

1977 – The Justice for Juveniles Group, previously known as the Wilson Protest Group, was established to bring about much-needed changes in Wilson through community education and action. This group conducted successful campaigns around such issues as lack of education, solitary confinement, lack of legal representation in the Children’s Courts, etc.

By this stage the ‘Hospital’ accommodated 68 boys and 32 girls. It was considered a ‘closed’ institution meaning that children were not free to come and go at will.

1980 – The Justice for Juveniles Group assisted with formulating the proposal and seeking funding for the establishment of the Youth Advocacy Centre.

1981 – The Juveniles for Justice Group were eventually successful and Brisbane’s Youth Advocacy Centre was established.

1983 – Responsibility for the Wilson Youth Hospital was transferred to the Department of Children Services and it was renamed the Sir Leslie Wilson Youth Centre after the Governor, Sir Leslie Wilson.

1993 – The Centre was again renamed: Sir Leslie Wilson Youth Detention Centre.

1995 – The Wilson Detention Centre became the only facility in Queensland to accommodate young females.

1999 – The Forde Inquiry into the Abuse of Children in Queensland Institutions recommended that the Sir Leslie Wilson Detention Centre Close as a matter of urgency.

2001 – The Wilson Detention Centre was closed on February 7 by the local member Premier Peter Beattie. Later that year the Centre was demolished

An excerpt from Fr Wally Dethlefs’ book: Journey into Gospel Justice: The Faith Development of a Diocesan Priest:

Wilson Youth Hospital

In August 1973, we became involved in Wilson Youth Hospital, a remand, assessment, and treatment centre for young people, in fact a prison for juveniles, in the nearby suburb of Windsor. It was to change my life drastically. A woman phoned the Lodge. Her fourteen year old niece who was in Wilson and who wanted to see a Catholic priest. When Pat went to Wilson, he was told a Catholic priest had not visited for some six months. When he came home, he told me about his visit and asked me if I would be prepared to share the chaplaincy with him. I agreed.

In early September 1973, Pat and I formally applied to visit Wilson, as chaplains on a regular basis. In December 1973, permission was given for Pat “to visit when required” and for me to “visit at the present time whilst Father Tynan is on annual leave and also when Father Tynan is unavailable”.[1] It was never made clear that I was to be merely a stand-in when Pat was not available.

From August 1973 until December 1974, Pat and I shared chaplaincy responsibilities at Wilson Youth Hospital – a juvenile prison for young people between the ages of eight and seventeen years for girls, and eight and fifteen years for boys.

On my first visits to Wilson, I could not believe what I saw taking place. Most, but not all, of the young inmates found their way into Wilson through the Children’s Courts. Many young people – in fact, most of the girls on their first admission – were placed in Wilson for non-criminal offences. These were called ‘status offences’, like running away from home, being uncontrollable, living in moral danger, or likely to lapse into a life of vice or crime.[2] If these offences were proven, and hearsay evidence was sufficient, the young people often received a Care and Control Order, which meant that they were placed under the Care and Control of the Director of Children’s Services until they were eighteen years of age. Under this Order, the Director could place his charges in secure custody. Most of these young people were leaving home because of violence. For the young women, the violence was often sexual.

I found many things which horrified me in Wilson.

Indeterminate sentencing was one of them. Since most Care and Control orders were valid until the young person reached eighteen years of age, they could in theory, stay in custody until their eighteenth birthday. Indeterminate sentencing meant, in practice, that young people never knew when they were to be released. Their release depended on a number of factors: the way they responded to the ‘treatment’ they received while incarcerated, the availability of accommodation on the outside, and the way they reacted to being locked up. Once they were placed on a Care and Control Order, they could, after release, be placed back in Wilson without reference to the Children’s Court.

There was solitary confinement, either in Open Tantrum or, as it was often called, “the fish bowl” (a room with a glass wall), or in Closed Tantrum which was simply a cell with a bed base built into the floor and a small window high up on the wall. Regulations prescribed that young people should be placed in seclusion for one hour, and then only with a staff person in close attendance. However, these regulations were often contravened. In fact, many young people spent days at a time in solitary confinement. One fifteen year old girl, Teresa, spent three and a half weeks in solitary before she was certified as being mentally unbalanced and transferred to Osler House at Wolston Park Mental Hospital, the lock-up section for adult women who were judged to be criminally insane. But that was another long and sad story.

There were no trained teachers in Wilson and, therefore, no schooling, an obvious breach of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child, as well as of a State law requiring compulsory education to the age of fifteen.[3] In the words of the psychiatrist in charge of Youth Welfare and Guidance in the Health Department, Dr B.J. Phillips, “education for these children was contra-indicated.”[4] In fact, many children in Wilson were illiterate, but even they were not helped to gain basic literacy-numeracy skills. Moreover, even a young person who had not been truanting and had been coping well at school was way behind his or her classmates when he or she returned to school because he or she was unable to continue with schooling while in Wilson. Even if a young person spent only three months in Wilson, he/she was so far behind his/her classmates that he/she effectively lost a year of schooling.

Julie was fourteen years when she went to Wilson. She was doing quite well at school in Year Nine, and wanted to continue with her schooling while in Wilson. At first, she was refused. After six weeks of persistent requests, she was allowed to do her schooling by correspondence, which meant that she had to sit in a room by herself all day, without any assistance. She approached me, to see if I could obtain a book she needed for her French studies. She also needed a tutor for maths with which she was having some difficulties. I was able to obtain the book she requested and to enlist the voluntary services of a qualified teacher who was prepared to tutor her in maths one or two hours per week, at the convenience of management and staff at Wilson.

I approached the manager of Wilson, the Major, (he was a retired Army Major), to arrange for the handing over of the book and to organise for her to be tutored. The Major said neither was possible – it would establish precedents. “Other children would be wanting books and tutors,” he said, “and the whole thing could get out of hand very quickly.” Unbelievable stuff.

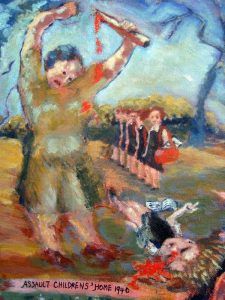

Wilson institutionalised violence. Most children had not committed serious crimes, contrary to what the Minister for Children’s Services, Mr John Herbert, often used to say: “Wilson is full of murderers, rapists and arsonists”. In the three years I worked there, I met two arsonists, but never a rapist nor a murderer. Most of the young people had run away from violence at home, been deemed uncontrollable by the court and incarcerated. Many young women I met in Wilson had been victims of sexual violence in their homes.

The young people who were sent to Wilson were dehumanised, brutalised, victimised and criminalised. On a number of occasions, staff told me that their young charges were “savages”. I saw young people with broken arms which they had received from staff who were supposedly “restraining” them. One girl suffered a fractured skull when staff dragged her upstairs by her legs. Her head bounced on the edge of the steps, and she was later admitted to the Royal Brisbane Hospital for treatment.

Vicki, a very intelligent and courageous girl, told me about this incident. She was so enraged by the violence of some of the staff that she fully intended to report the incident to the visiting magistrate who appeared at Wilson once every month. However, she was prevailed upon by staff not to take any further action. They told her, “Remember you have to live here. Staff will not take kindly to you reporting them. Also, staff members have families and your action could result in them losing their jobs and, if their families suffered, that would be your fault and on your conscience.” When Vicki told me that she did not have the courage to write up a report for the magistrate, she broke down and cried.

There is no doubt in my mind that some of the staff were sexually abusing both boys and girls. I knew of several cases that came before the courts, when staff were charged with sexual offences, but, as the courts were closed when minors were giving evidence, I was unable to find out the determination of the court.

In my opinion, staff were also using drugs to control the young people. Young people were often injected with sedatives. If some staff wanted to have a quiet shift, they were not above giving sedatives to their young charges. Some young people who did not have a drug problem when they entered Wilson certainly had a raging habit by the time they were discharged. I often spoke publicly about what I termed the misuse of legal drugs in Wilson. On one occasion, I was given a verbal warning, supposedly from Dr B.J.Phillips, saying that if ever I mentioned it again I would be brought before the courts. That worried me for a short time, but then I reasoned that a court case would be worth losing: the associated publicity would surely highlight the terrible things which were occurring in Wilson. I continued to speak publicly about the misuse of drugs in Wilson and heard no more from “B. J.”

In Wilson, all young people were ‘treated’ with incarceration, and seen by psychiatrists. If a young person was incarcerated for truanting, running away from a violent home situation, shoplifting, or a serious criminal offence, she/he was treated psychiatrically, with the result that the young person regarded themselves as “mad” because they had been treated by psychiatrists. And, because they had been incarcerated, most young people upon release were also convinced that they were “bad”. So the result of their time in Wilson was the double stigma of being “mad” and “bad”. Years later, many young people are still struggling with this slur on their character and their consequent negative self-images.

I must admit that I found it difficult to believe that our so-called civilised society could treat vulnerable young people in such a harrowing way. The only parallel situation which I had heard of was the psychiatric treatment of political prisoners in Siberia, by the government of the former Soviet Union. On many occasions, I was all but reduced to tears by the stories I heard from young people in Wilson.

One story, one of many similar stories, may illustrate what I have been saying. Glenn (a pseudonym) was the eldest of four children. His father had left the family home soon after the youngest was born. His mother battled on alone. When Glenn was twelve years old, his mother had a nervous breakdown and could not get out of bed. Glenn assumed responsibility for his mother, his brothers and sister for the next few days. He cut lunches, got the children off to school, did the cleaning and the cooking, but his mother seemed to be getting worse and Glenn did not know what to do.

He spoke to his class teacher, who couldn’t assist him in any practical way. He spoke to the neighbours, who didn’t want to become involved. There was no food in the house, so Glenn reluctantly decided to steal some fruit and vegetables from the local greengrocers. He told me three years later that he was not a thief, that he hated stealing, but did not know how else to feed his mum and the kids.

The greengrocer caught him stealing and called the police. ‘The welfare’ were called in. Glenn’s mum was placed in a psychiatric institution, his brothers and sister placed in children’s institutions, and his sister later fostered out. Glenn, however, suffered a worse fate. He was charged with stealing and placed on remand in Wilson Youth Hospital. He appeared in Court, unrepresented, and was placed under the Care and Control of the Director of Children’s Services until he was eighteen.

Two weeks later, he was placed in a Church-run boys home which he told me he hated, because of the violence of the staff who bashed the boys. The other thing he detested about the place was that, when a boy had infringed the rules, he was placed in a boxing ring with an older and bigger boy and thrashed in front of the other boys. Glenn loathed this violence. He coped in that place for three years by keeping his nose clean, his trap shut and learning to defend himself. He told me that, when he was placed in the boxing ring with a smaller boy, he would not hurt him. He would rather incur the wrath of the staff and the ridicule of his peers than participate in organised and institutionally sanctioned bullying.

Upon release from the boy’s home, Glenn had nowhere to go. He hated Christians. One night, he rang me at the Lodge, I don’t know on whose suggestion. He had been living with two young men at Manly. The eldest of the three was working and paying the rent, and had decided to move on. Glenn said he needed accommodation and needed it immediately. I told him we had a spare bed. It was then that he told me his mate needed a bed as well.

I arrived there about eight o’clock. The electricity had been switched off, and Glenn and his mate were sitting on the floor in total darkness. I chatted with them for awhile and then asked them to get their gear together and come and stay with us at the Lodge. They had a small bag each, in which they carried all their possessions. They had no food. Glenn told me that he had asked the local shopkeeper for some food and was not only refused but threatened with the police. Glenn certainly did not want to steal, and absolutely did not want to have any involvement with the police. He had decided to ask for help.

Glenn was at the Lodge three days before he found out that I was a Catholic priest. He came to me and asked, “Are you a priest?”

“Yes,” I said. “Why?”

“If I had known that when you picked us up the other night, I wouldn’t have come with you. I hate priests and I hate Christians”.

It was then that he told me about the treatment that was meted out to him and others in the church-run boys home.

I asked him if he wanted me to find another place for him and his mate to stay.

“You’re all right”, he answered. “I’d like to stay on here until I get a job and can set myself up”.

Glenn did that. He was with us for six months. He kept on trying for work until he was taken on by a volunteer at the Lodge who ran his own business. Every Sunday, he would get dressed up in his best gear, jeans and T-shirt, and catch a train to visit his mother who was still in a psychiatric hospital, and then his brothers, and finally his sister who was living with a foster family on the north side of Brisbane. Glenn often said to me, “If only there had been help available, my family would not have needed to be split up”.

On a lighter note, I took Glenn to an interview for a job as a labourer one morning. Glenn was fifteen or sixteen, well built and strong, but not very articulate. There were thirty others applying for the one job and Glenn missed out. On the way back to the Lodge, we dropped into Toombul Shopping Town. I had to exchange a shirt I had been given for Christmas which was too small.

Glenn was dressed for work. The lady shop assistant I approached looked at Glenn and intimated to me that we may have stolen the garment. She said she could not do anything until she consulted her manager. We waited until he came. He was a little man whom I would describe as a ponce. He gave us a lecture and mentioned the word ‘shoplifting’. Finally, he offhandedly waved to a row of racks and told us to get another shirt from there. I found one that I liked. Glenn and I took it back to this little, impeccably groomed and well dressed manager who continued to berate us. In the middle of the scolding, Glenn took me aside.

“Would you like me to re-arrange his face?” he inquired.

“No”, I said. “He’s only doing his job.”

“I don’t like his attitude. Nobody should be allowed to talk like that, particularly to you. Just let me tap him on the face”.

“No”, I replied emphatically. “Thanks all the same, but violence is not the way to solve problems.”

We left the store soon afterwards. That manager never realised just how close he had come to having his features altered.

Another story. Mary Anne (another pseudonym) was still a baby when her mother sent her to her grandmother to be cared for. As Mary Anne grew up, she called her grandmother “Mum” because her grandmother was a real “mum” to her and the only mum she had anyway, as far as she knew. Nobody told Mary Anne anything different.

When Mary Anne was eight years old, her mother remarried and, on the wedding day, took Mary Anne from her grandmother to live with her and her step-father. The experience was traumatic. She tried hard to fit into the new situation, but could never bring herself to call her real mum “Mum.” She called her mother by her first name, which her mother resented. Her real mum and her step-father both drank heavily, and prevented Mary Anne from seeing her grandmother “mum”, who lived on the outskirts of Brisbane.

Mary Anne was a good student who caught onto things easily at school. However, as the home situation became progressively worse, with her parents drinking and arguing most nights until the early hours of the morning, Mary Anne started skipping out of school and spending time with her friends, because as she said, “They are in a similar situation as me and because of that everybody understands everybody else”.

Her parents resented her spending time in this way and reported her to the police. She was charged with being uncontrollable and, because she continued to skip out of home, she appeared before the Children’s Court and was committed to Wilson Youth Hospital where she stayed for six months. During her stay in Wilson, she was unable to continue her school work and got further behind in her studies. She asked to be sent to her grandmother upon discharge, but her request was refused and she was sent home to her mother and her step-father. Of course, she ran away again and, subsequently, was returned to Wilson. Her grandmother wrote to her while she was in Wilson, but the letters were withheld from Mary Anne. Mary Anne also wrote to her grandmother, but the institution did not forward the letters. Mary Anne often wondered why her grandmother never replied. When she turned sixteen, Mary Anne moved back in with her grandmother. She obtained a job in the supermarket in a neighbouring suburb, and never again came to the notice of the police.

These homeless, disadvantaged and incarcerated young people were an oppressed, voiceless and powerless group of people. What was my God saying to me about them? Verses from the Bible began to jump out at me: were these the poor Jesus wanted us to tell the good news?[5] If so, what was the good news he wanted them to be told? Were these the prisoners Jesus had come to release? Were these young people the oppressed Jesus wanted to set free?[6] There was no doubt in my mind that this was so.

Then I came across these verses from Isaiah,

“Wash yourselves; make yourselves clean; remove the evil of your doings from before my eyes; cease to do evil, learn to do good; seek justice, rescue the oppressed, defend the orphan, plead for the widow. Come now, let us argue it out, says the Lord: though your sins are like scarlet, they shall be like snow; though they are red like crimson, they shall become like wool.”[7] (my emphasis)

God, through Isaiah, was saying, that Wilson was where I ought to be, living gospel justice for these little ones who were voiceless, powerless and oppressed.

Pat and I attended Wilson for one half-day each week, and we saw young people mostly in one-to-one situations. When they were nearing release, we gave them slips of paper with our name, address and phone number, and encouraged them to make contact with us if they needed. We also went there on Sunday mornings to celebrate Mass. It was not too long after we started work at Wilson that the young people who had been incarcerated in Wilson began turning up at the Lodge requesting shelter. We took them in, and tried to help them to the best of our ability.

The first two young people whom we accommodated at the Lodge were girls from Wilson. It happened this way. I was woken by the phone very late one night. It was the Juvenile Aid Bureau at the Clayfield Police Station asking if I would come over. They had two young women, Katie and Karen, whom Pat and I had met in Wilson. The police had contacted their parents, in fact, one of their mothers was at the police station. The girls were homeless, the police said. Their parents did not want them. Karen’s mother said that she was about to enter into a new relationship with an airline pilot. She tearfully told me that she did not want her daughter around to complicate things. The police said that they were reluctant to place the girls back in Wilson as they had not committed a crime, and they were unimpressed with the way Wilson dealt with young people. However, they had no alternative except, as the girls had mentioned, maybe, the Lodge.

I knew enough about Wilson at that time to agree totally with them. I had never anticipated living with young people. Here was a genuine need. What else could I do but respond? I took the girls home and made up beds for them in one of the upstairs rooms.

The next morning at breakfast, I said to Pat, “Did you hear the phone go last night?” He hadn’t.

I said, “How do you feel about homeless young people living here?”

He was pleased that I had bought Katie and Karen home, rather than have them placed back in Wilson, but the questions were: what would we do with them, now that they were living at the Lodge? How would we deal with Children’s Services? What would these young people do each day?

From a Biblical perspective it was easy. We had only to reflect on such readings as Matthew,

“for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me ….. And the king will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me'”.[8]

The Last Judgement text, as it is often called, spells out in a practical way what is important in the eyes of Jesus. It points to a practical living out of our beliefs in the circumstances of our lives. It specifically focuses on the stranger, the prisoner, the ones who are hungry and thirsty and calls them “members of my family.” Who were Pat and I to argue?

The text did not, however, answer the practical questions. It did not feed these young people or clothe them. It did not tell us how we were to deal with them, except to indicate to us that they were special and must be treated with respect. We trusted in our God, and decided to get on with it, reflecting as we went, acknowledging our mistakes and limitations, and often asking for assistance from our friends and those who had more skills than we did.

In a short space of time, the Lodge became a hive of activity. There were live-ins for YCS and YCW members on a regular basis, and some YCS and YCW people who needed time out from home because of alcoholism were using the place from time to time. There were various meetings, for example, YCS, YCW or Tertiary Students. We celebrated Mass several times each week, and those who wished were welcome to attend. Other groups used the place for one-off meetings. On top of all this, ex-Wilson young people were calling in for a chat, or asking to stay.

[1] Letter from Manager of Wilson Youth Hospital to the Director of Children’s Services, dated 17th December 1973.

NB. This and subsequent similar material was obtained from files released under Freedom of Information twenty years later.

[2] Children’s Services Act 1965: Sections 60 & 61.

[3] United Nation Declaration of the Rights of the Child states that the child is entitled to receive education which shall be free and compulsory (Principle 7.) Section 28 of the Queensland Education Act (1964-1974) states that “every parent of a child being of the age of compulsory attendance shall, unless some reasonable excuse exists, cause such child to attend a State school on each school day”. What applies to parents surely must apply to those acting in the name of parents (in loco parentis) and in the best interests of the child.

A number of the young people who had been incarcerated in Wilson and whose education had therefore ceased have often remarked that this played a significant part in condemning them to a life of poverty.

[4] See, for instance, the letter from the Hon. Mr Herbert, Minister for Welfare, to the Hon. Mr Knox, Deputy Premier and Treasurer, undated (but I estimate it to have been written in March or April 1978). Mr Herbert states, on page 2: “The children who are undergoing psycho-therapy under the control of Officers of the Division of Youth Welfare and Guidance do not (receive education) because, on the advice of the Senior Medical director, Division of Youth Welfare and Guidance, remedial teaching is contra-indicated for these children”. (my emphasis)

[5] Luke 4:16-18.

[6] Luke 4:18.

[7] Isaiah 1:16-18.

[8] Matthew 25:35 & 40