‘Christiana, in our eyes you were a success’, said Leicester about his mother at her funeral. Leicester’s eulogy is an account of his history and a tribute to Christiana. It also offers insights into how children were institutionalised in Australia.

Eulogy of Christiana Imelda Ramsey

Christiana Imelda Ramsey was born on 26th December, 1925 in St. Murdock’s Terrace, Ballina, County Mayo, Eire. She grew up in Limerick. Her parents were, Tom Daly and Mary Daly nee Hayes. Christiana’s parents eloped when her mother Mary was only 16 years old and they were married in England in 1920. Her grandfather, Pat Hayes, never forgave his favourite daughter, Mary and never spoke to Mary or her children for the rest of his life. He never forgave them for eloping, even when Christina’s mother Mary was ill in bed for nine years dying at the age of only 43.

Christiana always loved her mother and missed her for the rest of her life. She would often recall many fond memories of her time with her mother.

Christiana would recall visiting her grandfather’s farm at Palace Green for holidays between the ages of 4 to 8. She had been told she was not to talk to her grandfather, or even wave to him when he was watching from the window.

Christiana was one of 10 children: 6 girls 4 boys. Her father, Tom Daly, a mechanic by trade, was one of the founders of the original IRA. He was a TD, which is a member of the Republic of Ireland Parliament. He was also involved in the 1930-31 riots in Ireland. He drove the first bus in Dublin and also raced cars.

Christiana met many famous people in her life, including de Valera at the age of 5 and Michael Collins.

Christiana was proud to tell all those who would listen, how she sang in the St Johns Cathedral choir, Limerick at the ordination of a bishop.

At the age of 15 Christiana left home to start work doing cleaning jobs and errands for well to do families. After several years, she decided it was time to look for husband. She advertised in the paper and received many offers. These included a jockey. She decided to meet a Mr Harold Franklin Ramsey, a wealthy self made man who was looking for a house keeper, not a wife. On meeting him she accepted a job with him and over time they fell in love, a love that was to last the rest of her life. Even though there was a 33 year age difference between them. Sadly, he died when Christiana was in the prime of her life. She never remarried nor had a partner, because of her love for Mr Ramsey.

They were married twice, once in 1946 Royal Court England and in 1951 on Jersey in the Channel Islands.

Christiana and Mr Ramsey, as she often called him, travelled the world. They lived in Ireland, France, Switzerland, Ceylon, Jamaica and Jersey. They had 6 children and were internationalists before it was common. Their children were born in various countries, Anthony in Switzerland, Alan on Jersey, Michael and Chester back in Ireland and finally, Leicester and Malcolm in Australia.

After living and running a business on Jersey for 5 years, Mr Ramsey, who had been told stories about Australia by his friend the BBC war time correspondent Chester Wilmot decided to emigrate. Mr Wilmot was the author of the book ‘Struggle for Europe’. They decided Australia was the place of the future. So they set of from Jersey in 1949 motoring through France, Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, Turkey, Syria, Israel, the Holy Land, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran, Pakistan and India. In India they visited, amongst other sites, the Taj Mahal. Christiana always said that it was one of the most beautiful sites she had ever seen. From India they went to Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, where they waited for 6 weeks to catch a boat to Fremantle, Australia. On arriving in Australia, they were greeted by a reporter from the Western Australian newspaper. They were front page news for having been the first to travel by car from England to Australia, arriving in 1954.

They arrived with 4 children, Anthony, Alan, Michael and Chester. Leicester and Malcolm were born later in Australia.

After arriving in Fremantle, they then set off across the Nullabor Plain, which was then just a dirt track, to Victoria. Then they travelled up the east coast to NSW passing through Kiama, to Sydney. Not finding what they wanted, they returned to Kiama to settle. Kiama reminded Christiana of Ireland, with the green hills.

They set about finding land to build a garage and motel which they called the Shamrock Motel. The land was purchased at Ocean View.

Later, Christiana was contacted by her sister Mary. Mary asked if Mr Ramsey would pay the travel fares to Australia, for Mary, her husband Bill and their children so they could emigrate to Australia. Mr Ramsey and Christiana needed an assistant to run the hotel. So, they agreed, on the condition that Bill would work for Mr Ramsey until the money was paid back. Bill Wilson worked for a few months and never repaid the money owed. In fact, he not only refused to pay the money back, but 6 weeks before Mr Ramsey died, Bill Wilson, then 33 years old, attacked and punched Mr Ramsey, leading to his death soon after.

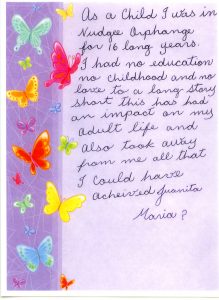

Christiana at 33 years of age was left widowed to raise 6 boys, the eldest 12 and the youngest 3 months. With no family or friends to provided support and help she was struggling to manage the running of a motel and garage. She was also struggling emotionally from her loss. Eventually, she suffered a mental break down and neglected to get all the children to school.

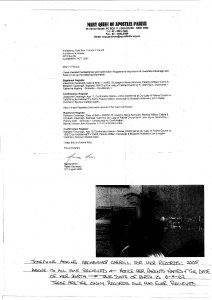

The authorities, concerned with the lack of attendance at school, called the police. The family property was raided, the front door was kicked in and the family dog was shot. The children were forcefully removed from Christiana. The children were then placed in the Bernardo homes at Kiama. Mary was not happy to have the children brought up in the Protestant faith of their father. Also, Mary was concerned about the environment of hate that existed between the Catholics and the Protestants in 1960s. She contacted Father Phibbs, then head of the Catholic child welfare bureau. Fr Phibbs made an application through the courts to become the guardian of the children until each one turned 16 years of age. He also had power of attorney over an estate worth in excess of 100,000 pounds. In today’s terms that would have amounted to millions of dollars. To this day, this money has never to be accounted for.

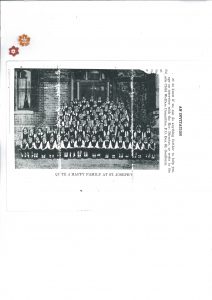

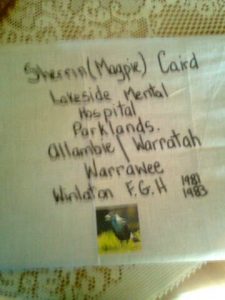

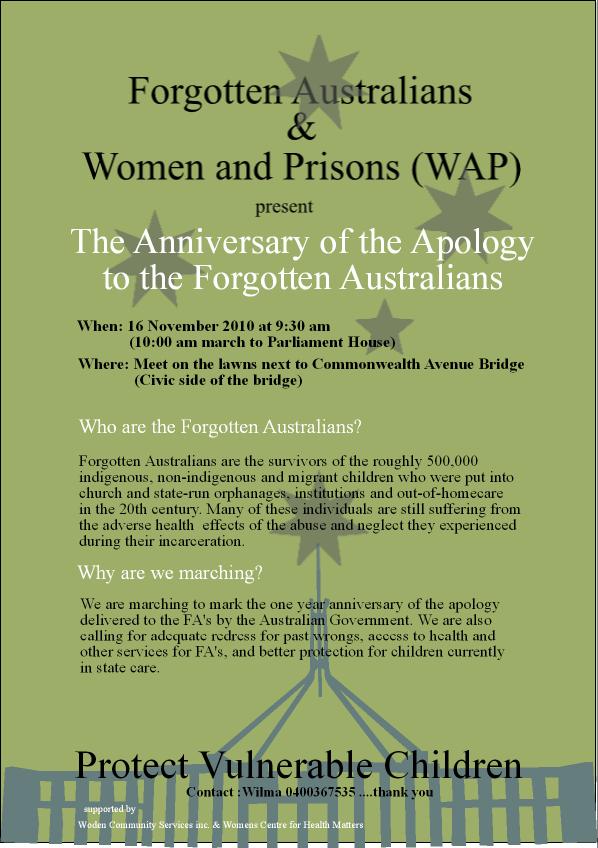

The children were then placed in St Joseph’s, St Michael’s and St Vincent’s Westmead. These unlawful acts were recently recognised when the Federal and State Governments apologised to the FORGOTTEN Generation and these children were invited to the ceremony.

Christiana in the meantime was placed in mental institutions and given shock therapy. After receiving treatment, she found work at the Australia Hotel making beds and cleaning rooms. Later she got a job with the Catholic nuns at Rose Bay, where she was allowed to have Malcolm, her youngest son, live with her.

In 1966 she managed to rent a property in Jersey Road, Woollahra, for 6 months. This allowed Anthony, Alan, Leicester and Malcolm to live with her again … [she was] … again institutionalised.

After recovering, she again gained employment. She visited her family by walking from Sydney to Westmead. Upon arriving she was told that she had missed visiting hours and she could not see her children. Saddened, she then had to walk all the way back to Sydney.

Over the years she asked many times to be provided with money from the family estate. She wanted the money so she could buy a house and raise her children, all to no avail.

In despair, she wrote to Sir Roden Cutler, the Governor of NSW at the time. She was seeking assistance to get a housing commission house so she could raise her children. After being on a waiting list for 8 years, in December, 1969, through Sir Roden’s help, she got one in Green Valley, bringing her 3 younger children together for Christmas.

As the years rolled on, Christiana lived to see her children and grand children, grow and become successful. Although much of her life was lived in poverty, all she ever wanted to be, was a good wife and mother.

Christiana in our eyes you were a success. You were a wonderful person. You were an inspiration to us all. You were a mother to your children and a grandmother to your grand children.

You achieved your aims beyond your expectations.

You will live on in the hearts of all that knew and loved you, down through many generations.

We love you and will miss you.

God Bless You and keep you in his love.